Conservation

CALIFORNIA DREAMING

A PATH FORWARD FOR SOUTHERN STEELHEAD

First published in Volume 14, Issue 1 of The Flyfish Journal

Wandering through the parched hills and canyons of Southern California, it’s hard to imagine that southern steelhead once thrived in this ecosystem. With a range of roughly 450 coastline miles from the Tijuana to the Santa Maria rivers, the historical population of southern steelhead, Oncorhynchus mykiss, was once estimated between one and two million fish. While wild steelhead numbers are plunging everywhere, the situation in Southern California is perhaps the most critical. According to a report compiled for California department of Fish and Wildlife, just 177 adult fish were documented throughout their entire range from 1994-2018 (though the study authors note this likely underestimates total abundance). Losing southern steelhead, which are uniquely adapted to live in extreme conditions—including warmer water temperatures—bodes poorly for steelhead everywhere.

Despite having been listed as an endangered species since 1997, conservation of Southern California steelhead has been slow and piecemeal. Their decline is no surprise as cascading and coalescing threats build year after year. More than a century of industrial and agricultural production, combined with rampant development, have dramatically reduced the habitat and connectivity steelhead need to survive. A historic and persistent drought has further stressed populations already in freefall. The impediments to more concerted efforts to save them are complex but follow a similar arc as conservation efforts for other species. Among myriad threats facing these fish, the most dangerous may be inertia.

Even with nearly three decades of federal protection, and despite strong runs in streams like Malibu Creek, all of Los Angeles, Orange and San Diego counties were not originally designated as critical steelhead habitat under the federal Endangered Species Act listing. Protection was extended only to adult steelhead—the anadromous form of rainbow trout. Juvenile steelhead and native resident rainbow trout, many of which have anadromous genes even after being cut off from the ocean for over a century, were specifically excluded even though they provide a critical link connecting populations and increasing genetic diversity.

The silver lining for southern steelhead may be that we are finally waking up, thanks in part to conservation organizations that have been sounding the alarm with renewed urgency. CalTrout led a petition drive to list southern steelhead under the California Endangered Species Act (CESA), and in April 2022 the California Fish and Game Commission voted that the species may warrant listing, making them a candidate for full CESA protection. These are important steps, especially given the state’s historical indifference to southern steelhead, which have always taken a back seat to king and coho salmon, as well as steelhead in Northern California.

John McMillan, wild steelhead activist and biologist, after fishing outside of his father Bill McMillan’s house on the banks of the Skagit River, WA. Photo: Copi Vojta

How we got here matters less than where we go due to the southern steelhead’s importance to the species as a whole. The concept of nature’s perfection has been written about extensively and it’s easy to see southern steelhead in this light. These fish have adapted to survive in the intrinsically high-disturbance environments of Southern California with variable life trajectories. According to research funded by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, drought has always been a defining feature of their ecosystem, among other extreme thermo-climate events, and southern steelhead are especially adept at using the entire ecosystem to respond to changing conditions. These fish are so responsive that they manage to navigate the many sandbars that cut off their natal streams, sometimes for years at a time. When those sandbars do open, it can be for as little as a few days. They are also remarkably resistant to high water temperatures. Studies have shown that southern steelhead can tolerate water temperatures up to 77 degrees before they seek refuge, and there are instances of fish having survived in water up to 82 degrees. Northern salmonids in many rivers do not fare well in water consistently above 64 degrees or a daily maximum of 71 degrees. These southern fish not only persisted, but also thrived in extreme conditions until the 1960s when streams that still had runs in the thousands began to collapse.

The implications for northern steelhead—both cold-water strains like those found in the Skeena River and more thermally tolerant strains like those found in the interior Columbia River systems—are immense. John McMillan, science director of the Conservation Angler, adds an evolutionary perspective to the argument for saving specific populations that tolerate higher water temperatures.

“Either there could be strong selection for a particular genotype that is capable of growth in warmer water temperatures,” McMillan says, “in which case, strays from more southerly populations could survive really well and end up founding a new population that outcompetes the original (northern) stock that is less thermally tolerant. Or you could have epigenetic effects, whereby fish experience warmer water temperatures as eggs and that tunes their metabolism to help them use oxygen more efficiently in warmer temperatures.”

His hunch is that a combination of both will probably prevail naturally as fish move and adapt, depending on where the fish are located regionally and the extent of thermal tolerance in those stocks.

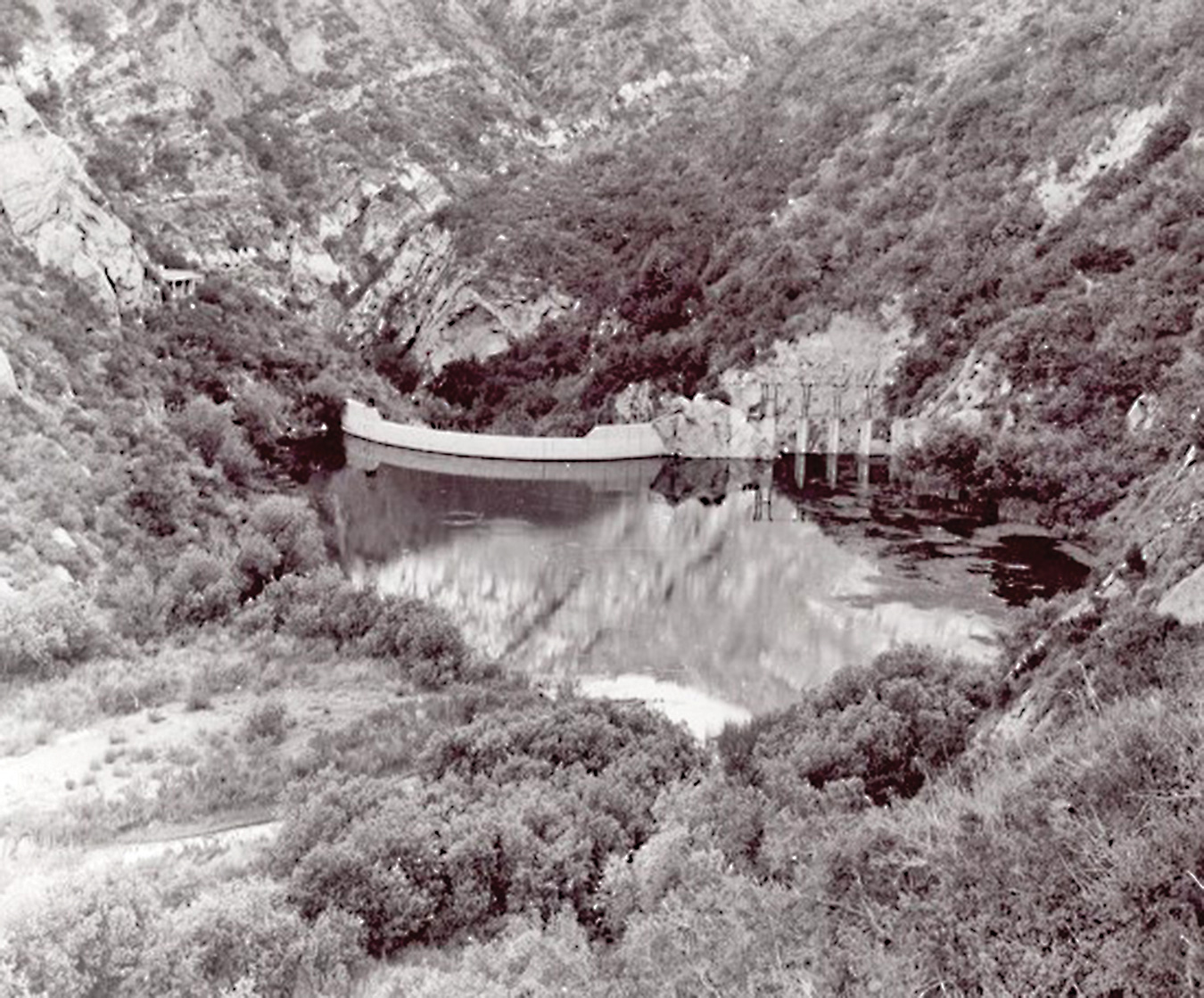

Rindge Dam on Malibu Creek, CA. After several wildfires in the area in the 1940s, and subsequent erosion of the surrounding hillsides, the dam became heavily silted in. Photo: Courtesy Malibu Adamson House Foundation

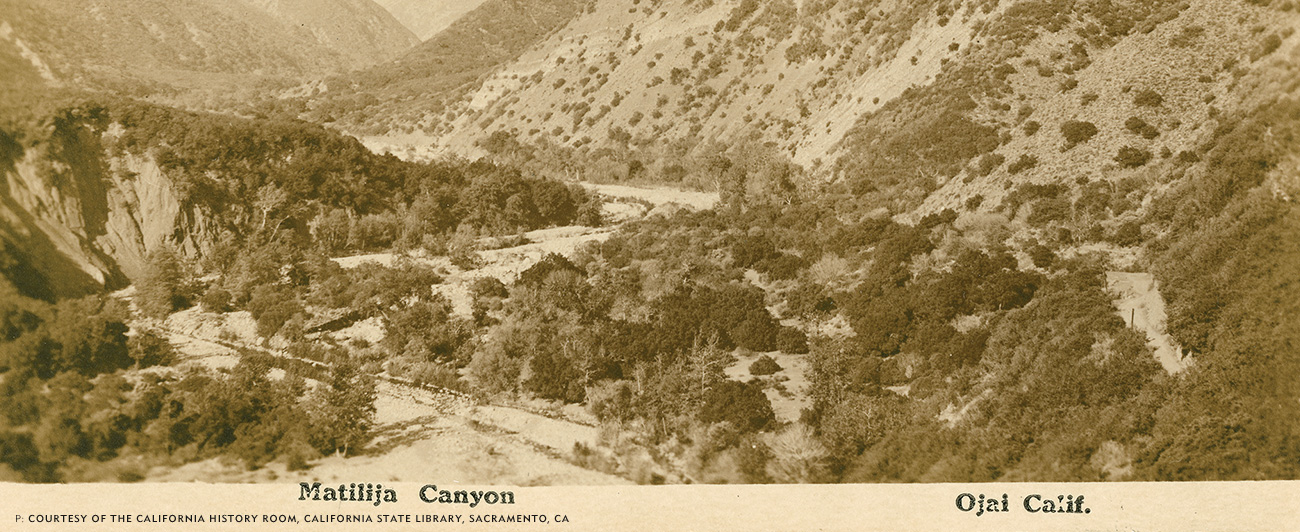

Saving southern steelhead is still possible, but the challenges are formidable. Of the three highest priority conservation objectives, removing stream barriers is the most immediate and impactful method to increase and preserve habitat and stream connectivity. Much of the highest-quality and most-remote southern steelhead habitat is currently locked behind dozens of obsolete stream barriers like Rindge Dam on Malibu Creek and Matilija Dam on Matilija Creek in Ventura, yet lack of funding and political will have hindered their removal. Rindge Dam was first studied for removal in 1992 and recent cost estimates to remove the dam were as high as $250 million. Southern California has also lost most of its lagoon habitat, a critical transition zone for steelhead, to filling for development. Restoration projects on several lagoons, including Topanga and Malibu creeks, are in the works, but face similar fiscal hurdles.

Two other critical conservation objectives are to increase stream flows, which will trigger steelhead to migrate upstream, and improve water quality. The latter has benefitted from environmental regulations initiated in the 1970s, but increasing streamflows will continue to be one of the state’s most fraught battles, with water resources drying up thanks to a decades-long drought and California’s thirsty water districts needing more water than ever. Steelhead move with high flows during winter rains. If they have suitable freshwater habitat in the mountains and no barriers to block their migration, they can complete their anadromous life journey.

Even if these conservation objectives are achieved, Rosi Dagit, senior conservation biologist of the Resource Conservation District of the Santa Monica Mountains, worries it may not be enough. Offshore, higher temperatures have induced thermal shifts, causing a ripple effect in the food chain that has disturbed sardine migration patterns. She argues that preserving southern steelhead is crucial because these fish have successfully navigated widely divergent ecosystem changes for millennia and will do so again.

Perhaps the largest hurdle facing southern steelhead is organizational, with myriad federal and state agencies, stakeholders and conservation organizations all needing to work together effectively. Fundamental questions have yet to be answered, such as who will administer a recovery plan over such a large and complex range, or how to prioritize certain drainages or population lineages. Sandy Jacobson, director of the South Coast and Sierra regions for CalTrout, believes the winning strategy will ultimately need to integrate endangered species recovery into community climate resiliency plans. Anadromous runs will need to be restored, along with protecting isolated native resident rainbow trout populations. The latter, which are now threatened by drought and wildfire, are remnants of historic steelhead runs. Until major migration barriers are removed, it may be necessary to pursue a translocation and gene-banking program for southern steelhead to provide a longer runway for regional recovery.

One of nature’s most dramatic characteristics is its juxtaposition of fragility with resiliency. In The Pursuit of Perfection: The Promise and Perils of Medical Enhancement, Sheila M. Rothman and David J. Rothman write that the forces of nature eventually overwhelm the best efforts of any individual or organism to conquer them. Southern steelhead have demonstrated time and again that they are one with the environment around them—the product of nature and an example of its properties, including its perpetuity. If that’s the case, we can hope that at some point the will of these fish to survive, along with recent developments such as the CESA petition and proposed lagoon restorations, will bring the possibility of recovery closer to becoming reality.