Adventure

The Ghosts of Casa Mar

above The Casa Mar lodge sits on the edge of Laguna Agua Dulce on the extreme northeast coast of Costa Rica just minutes by water from the Atlantic Ocean and the Nicaraguan border. In its heyday, the dock could get crowded after a day of chasing tarpon. Photo: Lefty Kreh

On June 7, 2007, a panga carrying a tarpon guide, his son and two clients—both gringos—flipped at the mouth of the Rio Colorado, near Costa Rica’s eastern border with Nicaragua. Three of the men died. The crew’s rods and tackle were tropical flotsam.

The Caribbean was churning, throwing up steep, 10-foot rollers at the river mouth. Chocolate waves crashed on shallow banks of volcanic sand, grinding like the guts of a cement truck. The 25-foot boat, the Don Cote, was “not properly inspected, licensed, registered or certified,” according to a New Jersey lawsuit filed by the deceased fisherman’s relatives. The water was “turbulent and choppy.” No life jackets were on board. The Coast Guard had issued warnings but the boat’s captain had chosen to fish anyway. Bad decisions were made, etc., etc.

Such details, while noteworthy in the United States, were hardly news to anyone in Costa Rica, where it was still standard practice to drive a car with a cerveza between one’s legs. Traffic lights, speed limits and seat belts were offered only as suggestions. The fact is, it was a tragic and ill-fated decision on a shitty day and these things can happen anywhere—but especially in places like Costa Rica. May the men who died rest in peace.

I learned these details because I’d been assigned to write the story. I’d taken a job as a reporter for a small English-language newspaper in Costa Rica, covering things like dengue fever, free trade and sewage treatment from San José, which is one of Central America’s least attractive cities. But the job came with perks. As the staff’s only angler, I’d inherited the paper’s fishing column after the longtime columnist died (natural causes—not fishing related).

The doomed boat had belonged to a once-famous tarpon lodge named Casa Mar. I didn’t know it at the time, but I was writing its obituary.

above Del Brown, who passed in 2003, was known as a pioneering permit fly angler. On his first trip to Casa Mar in 1975, he had no problem getting up close and personal with tarpon. Photo: Dan Blanton

If you wanted to catch tarpon on a fly circa 1970 you had a few choices, but nowhere near as many as today.

The Keys, of course, were coming into their prime. There were reports of good fishing off the Yucatan, but even Cancun was then just a few palapas on a pretty white beach. Belize was still a British colony. Cuba had gone to Castro and between there and the Panama Canal there was nothing but commies. Costa Rica, a country with no army or oil but plenty of tarpon, was the sole exception.

Against this backdrop, a small-time tackle-shop owner from San José named Carlos Barrantes first laid eyes on the Rio Colorado, a serpentine jewel that slithered through Costa Rica’s lowland Caribbean jungle. Barrantes, a lifelong fisherman and keen marketer, could only have been giddy at what he saw: The river, clean, cool, shrouded in old-growth rainforest, roiled with the silver-dark backs of thousands of rolling tarpon.

The bounty verged on biblical. The backwater lagoons sustained a daily barrage of giant snook and tarpon marauding baitfish, drum boiling on shrimp, machaca—a vegetarian blend of shad and piranha— smashing fallen flowers and fruit. Jaguar prowled the beaches, ripping the heads off sea turtles that sauntered onto the sand to nest at night. A rare species of blood-sucking dolphin left pallid snook floating about like scaly cadavers. At the top of the food chain were carnivorous, man-eating freshwater bull sharks that populated the river system all the way back to Lake Nicaragua, 112 miles inland.

Barrantes had stumbled upon the piscine equivalent of Jurassic Park and no one had ever fished it with a fly. With backing from a U.S. financier, he built a lodge on a nearby lagoon. They called it Casa Mar.

Barrantes had stumbled on the piscine equivalent of Jurassic Park and no one had ever fished it with a fly. With backing from a U.S. financier, he built a lodge on a nearby lagoon. They called it Casa Mar.

above left to right After a week of heavy rain, the River Princess, navigates the Rio Colorado in Costa Rica somewhere near Dos Bocas (“two mouths”) where the river splits around an island. Carrying passengers, cargo and supplies, these deliveries are vital to the remote villages up and down the river. The Rio Colorado eventually becomes the Rio San Juan in Nicaragua. Photo: Barry and Cathy Beck

The adornments on the walls of Casa Mar now function as a portal to another era of fly angling. The picture has faded and the snook mount is moldering. Everything has changed and nothing has changed. Photo: Dave Sherwood

Not long after the boating accident at the river mouth, I was frantically pounding keys in my downtown San José office, rain pelting tin overhead, when a call came in. Was I the new fishing writer? The man on the end of the line said his name was Peter Gorinsky. He told me he was originally from Guyana, in South America, but had moved to Costa Rica in 1972. British Guyana. Caribbean side. That explained the accent, a jovial blend of London and pirate. He’d helped to train the first tarpon guides at Casa Mar decades ago, he told me, and he had some stories to share. Did I have a car?

As it turned out, Peter lived on the flank of amountainside draped in coffee plantations just a few minutes uphill from the apartment I’d rented. Before hanging up the phone, we’d agreed to conduct a “fact-finding” mission to Barra del Colorado, the fishing village closest to Casa Mar. My editor conceded and two weeks later I picked Peter up at his home well before sunrise.

An older man—about 70, I guessed—white-haired, with a neatly cropped beard, floppy cheeks and a long-billed fishing cap waited by the door of a small white house beneath a rusty tin roof. A parrot squawked from inside. The man had fly rods in one hand and a tackle bag by his side. Behind him came a young boy, perhaps 12—dark-skinned, shy, with peering eyes and a mop of unkempt black hair. His name was Charlie. Peter said he would come along to observe, help out and perhaps take a cast or two.

From San José we drove east toward the Caribbean, across the cloud forest of the continental divide then down the backside into sweltering, sea-level Caribbean jungle. We talked about fishing, Guyana, his time at Casa Mar and his other passions: orchids, beekeeping, painting, gemology, psychopharmacology, eco-tourism. Who was this guy, anyway? Pot-holed pavement turned to washboard, then scree and finally mud. Emerald fields of banana and pineapple monoculture gave way to the disorder of jungle. Then, a river and the end of the road. Peter had arranged for a local fisherman to take us the rest of the way to Casa Mar.

He lived in a simple stilt shack with a palm-thatched roof. Inside, there was only a hammock, a machete, and a couple of sacks of rice, but his children attended university in San Jose.

above Tropical fish camps are not immune to the cycle of life. Casa Mar opened its doors to fishermen in the late 1960s, becoming one of the world’s premier tarpon destinations through the 1970s and ’80s. Since then, it’s been fading slowly back into the tropical rainforest. Photo: Dave Sherwood

On the river, the air was thick and hot. But there was a breeze, and it was sweet with the fragrance of water and earth, the perfect antidote to the drive. For an hour, we wound our way through a canyon of drooping rainforest trees and lianas, howler monkeys yo-yoing from branch to branch, stick-legged white egrets perched on sandbars, children splashing in dugout canoes. We rounded a bend into a long and narrow lagoon and there, in a clearing on loan from the jungle, was Casa Mar.

The lodge was open but there were no clients. The low, wooden buildings, still well maintained, were not grand, but elegant in their simplicity and the way they meshed with their surroundings. The grounds looked like a botanical garden, with tidy pink hibiscus hedges lining stone walkways that wound through a grove of coconut palms to small but tidy cabinas out back. The branches of an enormous mango tree spread like an evergreen umbrella over the main lodge, shading a pretty, turquoise-painted veranda lined with antique wooden benches.

Lefty, one of the lodge’s original Costa Rican guides, greeted us at the dock in a Casa Mar cap and white fishing shirt. He and Peter embraced. Peter had helped teach Lefty to guide flyfishermen in the 1970s—rigging tackle, tying knots, pinching barbs, releasing tarpon without harming them. Lefty had helped keep the lodge running, but told Peter business had fallen off since Billy’s death. Billy was Billy Barnes, the lodge’s longtime manager. After Billy died in 2002, Lefty said, lawyers and accountants from San José swooped in like zopilotes. Most everything had come to a halt, he said, except for the jungle. The fishing is not what it used to be, he said.

Inside, the place was a time warp. There was a dusty mount of a giant tarpon overhead, varnished tabletops sliced from the trunks of ancient rainforest trees, books signed by the other Lefty, foreign dignitaries, old military and nautical charts and flies in frames. Termites had invaded, leaving tidy piles of sawdust in each corner and beneath the tables, but the lodge was mostly intact. While Peter talked with Lefty, Charlie and I wandered. Black-and-white photos lined the walls of the dining hall. Even though Charlie hadn’t done any flyfishing, I could tell he was intrigued.

In the photos, the men were dressed in simple clothes. Shorts. A T-shirt. A ball cap. Leaping tarpon were framed against a backdrop of palm fronds and beach and open ocean. The fishing was pure and simple and there was no unnecessary clutter or technology.

Looking around, I felt a sucker punch of regret: These were the good old days and they were gone.

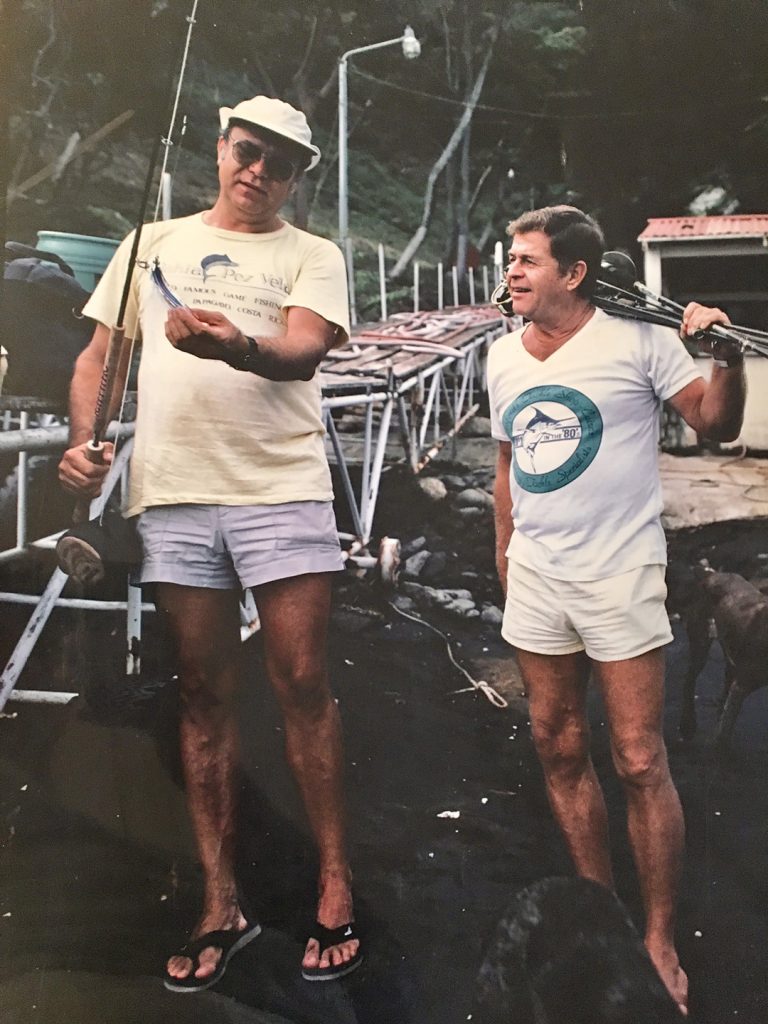

above Peter Gorinsky (left) and Bill Barnes gear up before an exploratory blue-water trip out of Casa Mar to search for tuna, sailfish, dorado and marlin. In the early 1980s, this was a new venture for Casa Mar and a change from the usual tarpon, snook and other freshwater lagoon species. Photo: Courtesy Peter Gorinsky

Peter told Charlie and I this was the first time he had been back to Casa Mar in years. The visit, the bumpy roads, the sun, the memories. He was tired. He wanted to fish.

Back on the lagoon in front of the lodge, the tide was going and the day’s accumulated insects and tree fruits and foliage washed into the channels. We tossed poppers into the fray. Mojarra, a tropical panfish, materialized from beneath the canopy. They are at the bottom of the food chain and like everything small and vulnerable in the jungle, cautious. Twitch, twitch. The fish turned, reluctant. Twitch, twitch. Now they were coming. Twitch. Each required coaxing. Once committed, they inhaled the fly with a smacking kiss then swam down and broadside, unyielding. In hand, their colors pulsed and glowed, like a bluegill plugged into a socket.

Peter’s casts landed amid the dense foliage as if hand-delivered, unfurling with a delicate but decided plop that seemed to call in the fish without spooking them. When clients complained of sore arms from catching too many tarpon, he told us, he would take them to the backwater lagoons for panfish on light fly rods. He was in his element.

Charlie asked to see what we were using as bait. As a young boy on his mother’s farm near the Nicaragua border, he’d caught guapote, or rainbow bass, on handlines and sardines. Charlie had shown up on Peter’s doorstep less than a year prior, unannounced. There were still some places where such informal arrangements dictate life. This was one of them.

Peter showed Charlie how to cast. Charlie looked at the fly rod, admired it, then he waved it back and forth, imitating Peter and I. I felt a bit effete. Ridiculous even. A fly rod is a toy for gringos. Charlie knew this. The practical way to catch fish is with bait. Then he caught one. He was interested now. He caught another.

Charlie took one last cast before dark and hooked a machaca, the toothy, tropical equivalent of a hump-backed shad. It vaulted into the air then sheered his tippet with its incisors. Charlie looked at me and then at Peter. His eyes were headlights.

above left to right “Although designed for big fish, early glass rods would eventually break down after landing many big river tarpon. This one blew up on well-known Californian Ed Given while doing battle with a fish well over 130-pounds.” Photo: Dan Blanton

“In the early 1970s in the swift jungle rivers at Casa Mar we were experimenting with tackle and how to fight big tarpon. It was a learning process. Hard to believe now but we used 5/0 hooks. We weren’t concerned about IGFA records, so we often used heavy leaders. Frequently, really big tarpon in swift current would open even these large hooks.” Photo: Lefty Kreh

“For a number of years, legendary saltwater pioneer Harry Kime spent about three months at Casa Mar fishing tarpon almost every day. There is no doubt in my mind Harry has caught more tarpon bigger than 60 pounds on a fly than anyone. He was modest and never said much about it.” Photo: Lefty Kreh

Not long before Carlos Barrantes began clearing away jungle to build Casa Mar, civil war broke out in Guyana, almost 2,000 miles south. Peter, born to a pioneer ranching family on the country’s vast Rupununi frontier, was forced to flee his home in exile after a shootout on a tarmac, his family farms razed, their cattle stolen.

Costa Rica beckoned. A pacifist country and the only one without an army in the region, it met Peter’s short list of requirements: an offer of residency, a tropical climate, good fishing. Shortly after his arrival, he rented an apartment in San José from Carlos Barrantes, the San José tackle shop owner who founded Casa Mar. Next door was Bill Barnes, the lodge’s soon-to-be owner and manager. Such happy coincidences were Peter’s specialty.

Peter learned to flyfish for peacock bass as a boy in the canals of Georgetown, Guyana’s capital, then caught obscure Amazonian freshwater species like arawana, arapaima and pacu on hand-tied flies decades before their names became known in the United States. Once in Costa Rica, he’d begun taking tourists out to flyfish for guapote, a rainbow-colored cichlid that devoured big poppers in a lake beneath the country’s most active volcano. It was Barnes who introduced him to tarpon.

Inside, the place is a time warp. There is a dusty mount of a giant tarpon overhead, varnished tabletops sliced from the trunks of ancient rainforest trees, books signed by the other Lefty, foreign dignitaries, old military and nautical charts and flies in frames.

above After a long day chasing tarpon, dinners at Casa Mar were not just for nourishment and trading stories—they were also for sharing techniques. These anglers were pioneering the use of special flies, lines, equipment and techniques of modern-day tarpon fishing.Photo: Lefty Kreh

North Americans, meanwhile, had already begun to flock to Casa Mar. Clients using both spin and fly gear were hauling humpbacked snook onto the beach that made the pipsqueaks coming out of the Everglades look like the JV squad. Anglers jumped dozens of tarpon a day on heavy tackle in the backwater lagoons, all from tidy, well-kept johnboats that became Casa Mar’s photo-perfect signature. Jim Chapralis, of flyfishing travel pioneer Safari Outfitters, had sent Dan Blanton, originator of the “Whistler” pattern, with a group to prove Rio Colorado tarpon could be caught on a fly rod. They caught more tarpon on a fly that trip than many Keys anglers would catch in a year. The resulting buzz attracted the biggest names in flyfishing: Lefty Kreh, Flip Pallot, Jim Vincent, Billy Pate, Mark Sosin, Jack Samson, Stu Apte, Harry Kime, Kay Brodney. They were passionate anglers, but also marketers, promoters, guides, photographers, authors, inventors, hustlers, pioneers. Word spread quickly.

“It was the place to be,” Peter recalled. “There were so many tarpon. You didn’t have to wait around a week to catch one. You could catch 10 or 20 in a day. We broke a lot of rods, but we learned a lot about how to handle big fish under these circumstances. It became the capital of big-fish flyfishing in Central America.”

Many of these early visitors took lessons gleaned in Costa Rica back to the United States, part of a virtuous cycle that led to the development and perfection of new techniques, flies, lines, knots and rods. Years later, Lefty Kreh, flyfishing’s patron-savant and a good friend of Barnes’, would declare that more tarpon had likely been caught at Casa Mar than any other place on the planet.

ABOVE Dan Blanton introduced Harry Kime to Casa Mar tarpon in 1975. Harry fell in love with the place and it eventually became a second home to him. He had his own cabin and would often spend the entire season at the lodge. Photo: Dan Blanton

above left to right With hopes of a beautiful week of tarpon fishing, there is nothing worse than a week of torrential downpour. After days of being landlocked at Casa Mar playing cards and eating ice cream, the weather finally allowed Lefty Kreh (left) and Bob Clouser a bit of a break—almost. Photo: Barry and Cathy Beck

Lefty Kreh, Ed Given and Dan Blanton yuk it up, circa March 1975. Not a single trucker hat or a stich of breathable, sun-resistant clothing to be seen. Photo: Courtesy Dan Blanton

Visitors came and went, but Peter stayed on in his newly adopted home. Fame and fortune eluded him, but fish did not. He absorbed information and techniques from anglers, then pioneered new destinations and species in Central and his native South America. Later, he founded the Costa Rican Association of Fly Fishers, a group to promote catch-and-release and ecotourism. A lifetime spent living and fishing on the tropical frontier had made him an authority with the type of knowledge you couldn’t glean from the internet.

After our first trip to Casa Mar, Peter, Charlie and I began fishing together on a monthly basis, sometimes more, depending on the season, the rains and our budget. We fished for machaca in the northern rivers, guapote in the Pacific-side lakes, trout in the cloud forests along the continental divide. Peter knew a boatman named Moncho in Barra del Colorado, the town closest to Casa Mar. He was typical of Peter’s local contacts—humble men and women befriended over decades of travels and fishing. Though not a fishing guide, Moncho was sinewy and tough and happy to paddle us all day at a bargain rate. Once, when he overslept, I followed a sandy track to his house to wake him. He lived in a simple stilt shack with a palm-thatched roof. Inside was only a hammock, a machete and a couple of sacks of rice, but his children attended university in San Jose.

Moncho paddled us along the rainforest edges of the lagoons around Casa Mar as we picked mojarra and guapote from thorny tangles and pockets. The young Charlie normally took a place in the bow, flailing a bit at first, but quickly learning under Peter’s tutelage. When the fishing slowed, Peter, always teaching and telling stories, passed along the wisdom of the tropics—the proper knots for stringing a hammock between coconut palms, how to tame a thrashing 200-pound tarpon, methods for distinguishing deadly snakes from the merely dangerous.

At midday, when the tropical heat grew oppressive, we nearly always stopped at Casa Mar. Though now-shuttered, the porch was shady and cool and the perfect place to plumb Peter for stories, peruse old photo albums and reminisce. Moncho would wait patiently for us at the dock, gathering ripe coconuts that had piled up on the grounds. Upon our return, he would slice them open with a sweep of his machete and hand one to each of us, toasting to the good old days. We fished until the call of keel-billed toucans, haunting and elegant, echoed in the canopy above, then returned to the nearby village of Barra for fresh fried fish with rice and beans.

There was no wet bar or Jacuzzi at the end of the day, but as Peter liked to point out, ours were the kinds of experiences money couldn’t buy.

“There were so many tarpon. You didn’t have to wait around a week to catch one. You could catch 10 or 20 in a day. We broke a lot of rods but we learned a lot about how to handle big fish under these circumstances. It became the capital of big-fish flyfishing in Central America.”—Peter Gorinsky

above “Because we were catching tarpon in deep jungle rivers, the fish had to be beaten to almost a standstill and then lip-gaffed at boat side. We did not use a kill gaff on them. They would often blow up, leaping while still attached to the lip gaff—very exciting moments. They would be pinned to the aluminum skiff by the lip, fly removed, revived and released. We had to do this quickly since there were many aggressive bull sharks prowling the river.”Photo: Dan Blanton

Between trips with Peter and my work as an environmental reporter, I slowly pieced together the story of Casa Mar’s demise. Things were idyllic at first, just as in the photos. Word spread and new lodges popped up along the river and lagoons: Isla de Pesca, Archie Field’s Rio Colorado Lodge, Tarponland, Silver King.

At first, the hype brought prosperity. Each lodge had its own local waitstaff, cooks, guides, boat mechanics. Dentists and doctors, frequent clients at Casa Mar, put on clinics in local villages. Barra’s airstrip was improved. But more boat traffic disturbed lagoons that had rarely known an outboard motor, causing erosion and sometimes putting down the very tarpon that attracted them in the first place. More delicate species, like manatees, fled.

And then there was the Nicaraguan Civil War of the mid-1980s. At night, when the trade winds settled, Peter remembers smoking his pipe on the porch at Casa Mar and hearing the U.S.-backed Contras exchanging gunfire with the Soviet-backed Sandinistas just a few miles to the north. This was ground zero in the Cold War and Casa Mar was smack in the middle of it.

“At the height of the battle, we’d be out fishing and see the bodies floating down from the war,” Peter said. “We’d say, ‘Oh, there goes a Contra,’ or, ‘Oops, there goes a Sandinista.’ But you couldn’t touch them because they were booby-trapped. When they drifted down to the river mouth, you’d hear the explosions. That made the sharks happy but it scared a lot of clients away.”

When the fighting stopped, the battle shifted to the environment. Nicaraguan refugees flooded Costa Rica, especially the border areas. Those who settled around Barra turned to fishing and, often out of desperation, drug running. The river’s signature population of freshwater bull sharks were decimated as the market price of their fins skyrocketed in China. Netting increased in the lagoons and at the river’s mouth. Upriver, settlers cleared virgin rainforest. Big multinational corporations followed. Vast monocultures of banana, and, in time, pineapple, replaced what was once unruly jungle. The river got shallower, wider and warmer. Wildly abundant bait and shrimp runs that once attracted tarpon and snook declined.

It was death by a million cuts, according to Peter. Some of the lodges hung on, modernizing and adapting to the new conditions. Tarpon could still be caught in good numbers outside the river’s mouth, but the guides at Casa Mar, in small and underpowered boats designed decades ago for river fishing, had been increasingly tempted to take chances to ensure their clients got their fish.

And then, the accident.

above Longtime Casa Mar manager Bill Barnes was known as a fine angler. His talents also applied to caimans. Photo: Lefty Kreh

Over years of fishing with Peter, what I’d suspected from that first phone call became clear: He was a legend. His stories of fishing and adventure were so fantastic, so far-fetched, it had been hard at first to believe them. The reporter in me—the skeptic—wondered: How could anybody have survived so many small plane crashes, civil wars, shootouts, snakebites and run-ins with drug czars, killer bees, bull sharks and black caimans? But then, as if he’d summoned God himself to reprimand us for not believing his every word, some unforeseen event would vindicate him.

Once, a coworker in San José called to tell me she had a 10-foot-long boa constrictor in her backyard. Her yorkie needed to pee and she wondered if I might come over to take a look. I didn’t know the first thing about snakes but rushed over anyway. The boa, backed into a corner and as big around as my leg, was a lot scarier in the flesh than I’d imagined over the phone. I called Peter.

How could anybody have survived so many small plane crashes, civil wars, shootouts, snakebites and run-ins with drug czars, killer bees, bull sharks and black caimans?

above Dick Gaumer jumping his first fly-rod tarpon. An excellent angler, Dick landed many during his week at Casa Mar. Photo: Dan Blanton

He and Charlie arrived 20 minutes later. By now, the three of us had fished together for several years and knew one another like family. Peter had told us no end of tropical snake stories in which he was, of course, nearly always the protagonist. Now, the moment of truth. Peter arrived and stepped from the car wearing a tweed cap. He walked with a limp and a cane, the result of a fall he’d taken the weekend before while a tarpon thrashed alongside our boat.

Peter handed us a rice sack in which to stow the snake, then approached the coiled boa with calmness that befit a pastor. With one deft and unhurried motion, he turned his cane on end and pinned the beast behind the head with its forked handle. Charlie and I stood a safe distance away, rice sack in hand, but paralyzed with fear. Peter bent over, picked up the snake from behind the head and strolled toward us.

“Well, don’t just stand there, you ninnies!” he barked. “Open the bag.”

ABOVE Fishing breeds the strangest—and most enduring—of relationships. Peter Gorinsky (left) informally adopted Charlie Chavarria nearly a decade ago. Charlie needed a home. Peter, aging, with health issues, needed help. Peter took Charlie under his wing, teaching him to cast, to tie flies and tarpon leaders, to speak English, to catch and release giant tarpon. Charlie is now a flyfishing guide himself. The tradition lives on. Photo: Dave Sherwood

My wife and I returned home to Maine in 2011. But Peter, Charlie and I still fish lagoons around Casa Mar every chance we get. Peter, now nearly 80, complains about his health and the heat and the poor fishing, but he always joins us. He still loves to fish more than he loves to eat.

On our last trip, the jungle had reclaimed what Carlos Barrantes, Casa Mar’s founder, borrowed from it four decades ago. A tree branch had fallen through the roof. Rain and insects followed. Squatters had moved into the boathouse fronting the water where anglers and guides once mingled. An old picture of Lefty Kreh hung over their makeshift bed, the glass mildewed, smoky and cracked. The lodge’s boats are all gone. It was a sad sight.

On the water, though, nothing had changed. The fish were there. Moncho was at the helm with his hand-carved wooden paddle. The banter on the boat was constant. Charlie had grown up. His casting was impeccable. He caught two mojarra to our every one. And his wit cut like a knife. He was relentless. “Tata,” he would say, summoning the endearing term for “father” in Spanish, then heckling me for lodging a fly in a shoreside bramble. “Do all gringos cast as poorly as David?”

When Peter would overreach with tales of having guided Sam Walton or Fidel Castro’s henchmen (nearly always rooted in truth but often improved with embellishments), Charlie sensed an opening. He never missed an opening. “Tata, isn’t it also true that you were the one that hatched the plan that brought down Hitler during the Second World War?”

above “All the top American flyfishermen came to Casa Mar,” says Peter Gorinsky, surveying what’s left of the lodge. “It was here they developed their techniques and gear for big-game fishing. They came because of the quality of fish we had, the number of fish we had. Casting techniques, line systems, fly rods, fly reels, drag systems. This was the ultimate testing ground. We would sit here every night and discuss and debate techniques for catching tarpon. There were so many tarpon. We used to see rods come in here broken in bits and pieces. Casa Mar was the mecca.”Photo: Dave Sherwood

Charlie had learned to speak English, tie flies, row a boat, deftly release a tarpon. He now enjoys a good glass of Malbec, likes his fillet on the rare side and is studying at a private university in San José. He can unravel a fly-rod popper through a leafy slot in the rainforest better than anyone I know. He is a full-time flyfishing guide, working together with Peter and following in his footsteps. He takes anglers for tarpon in newly discovered jungle lagoons in Costa Rica and Nicaragua, for trout and machaca in the mountain rivers, for sailfish on the Pacific. The clients rave about him. Every year there are more repeat customers. Peter sends me the letters, proud like a father would be. I’m proud too.

Casa Mar is gone. Those days are over. But looking back now, I think to myself, we are making our own story. The good old days live on. And I don’t feel so bad anymore.

This story originally appeared in The Flyfish Journal Volume 9 Issue 2.