Interview

Implements and Approaches: The Art of Ryan Keene

Keene studied sculpture, painting and printmaking at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. He was well into a career as a sculptor and builder when the dust of the crafts caught up to his lungs. It left him with a case of pneumonia that forced a change in the direction of his art. He returned to his childhood love of watercolor and combined it with his childhood love of fishing.

I recently spoke with Keene about his fishing and painting, and the relationship between nature and art. We talked about craft, but also about the poetic nature of how he sees the world, and how that translates into his painting.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

The Flyfish Journal: Can you give me a bit of your background: how you got into art and how you got into flyfishing?

Ryan Keene: My mom was always very artistically talented, so we spent a lot of time drawing nature: trees and seeds and flowers. The fishing side was my dad. He was a big flyfisherman and had a very poetic relationship to nature. Very often we’d go backpacking with a bag of trail mix and that was it. If we didn’t catch anything, we wouldn’t eat that night.

They were both hippies—there was an earthy, crunchy, barefoot in the forest kind of feeling. With those two teachings in my life, I really learned to understand and respect the natural world.

With fishing and the artwork, did your interest in one or the other really take hold first?

Because of the two sides of the coin with my family, I think they always kind of existed at the same time. When I was looking at going into more professional or “academic painting” I was definitely going away from the natural world. I started doing large abstracts, collages, Rauschenberg-feeling kind of things. But really up until then, it was fishing with my dad and water coloring birch trees with my mom. As long as I can remember they were competing for which side I decided to put more energy toward. They were both feeding a passion. They both started earlier than I can remember.

At what point did you combine those interests? It seems like you’re mostly painting fish at this point; is that right?

Yeah, it’s actually pretty recent. After school, I continued with the installation art. I was doing huge, room-sized things in steel mills and blast furnaces and galleries. I was definitely more immersed in that contemporary, postmodern kind of approach. They were always projects that took a lot of physical effort and a lot of building, which was kind of what I was doing for my day job as well. I was doing a lot of historic renovation of houses and windows and things like that. Then all the dust caught up to me and my lungs started failing. Throughout my life I haven’t had much immunity to things like pneumonia, and so I’ve had it 12 to 15 times. That’s kind left my lungs ravaged.

Four years ago on Christmas Eve I ended up in the hospital for a few weeks and never really came back 100 percent. I knew that a lot of things had to change, including my career. My in-laws had gifted me a little portable watercolor box, and as I was sitting in the hospital on Christmas Day, my escape was thinking back to being in the rivers with my dad and painting with my mom.

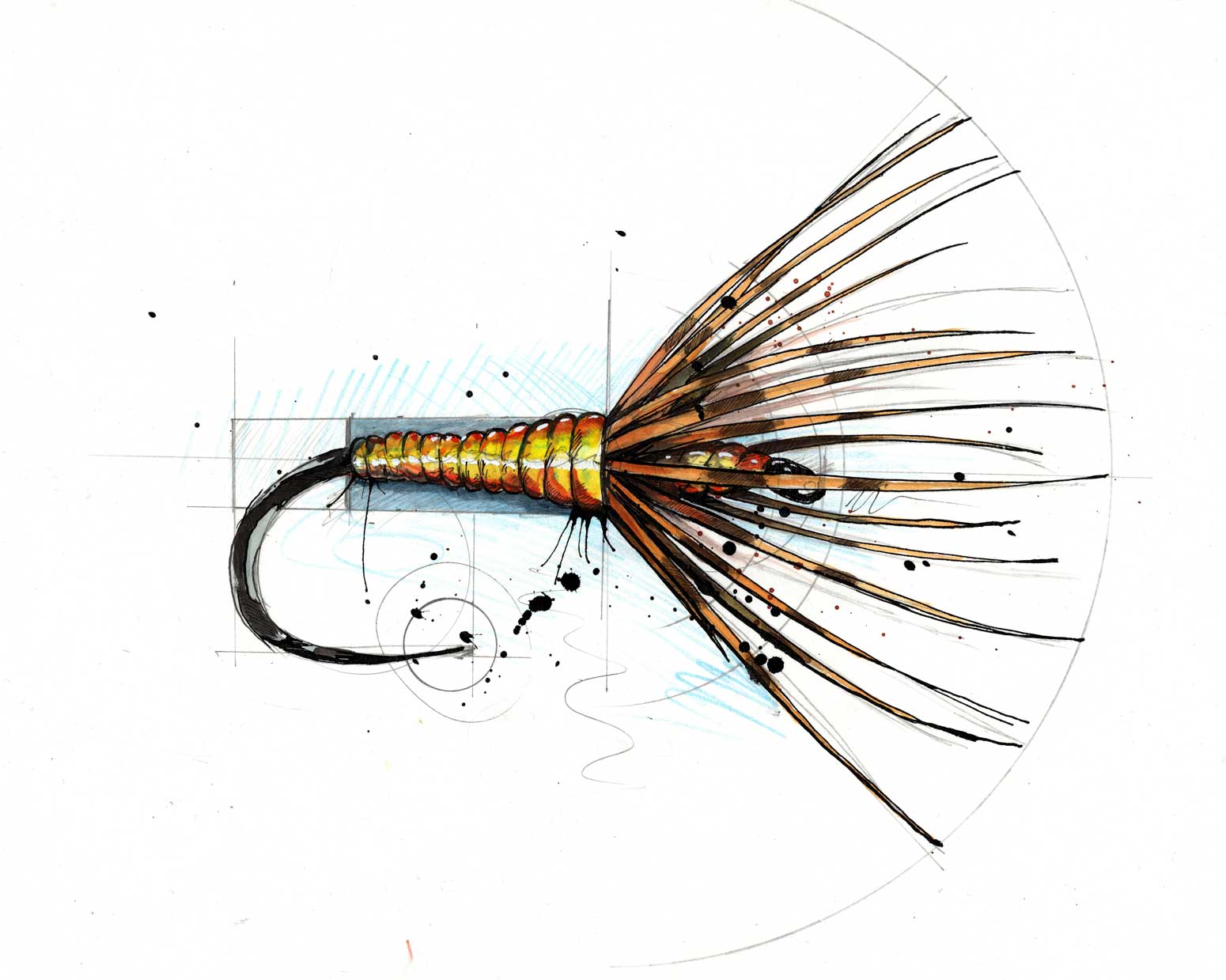

Watercolor gave me that kind of peace I needed at the time, while everything else was in question. And that followed me home where I couldn’t do all the things I’d normally be doing. I just continued painting flies and painting fish, those things I remembered from when I was a child and I didn’t have any concerns or worries. Call it a meditation or escape, whatever it might be. It was what I was relying on.

It’s interesting that watercolor was your way of both transitioning your career away from sculpture and your way of finding solace as you recovered from your illness.

Absolutely. It was that link to a lifestyle that I had kind of grown away from. After grad school life just took over, and I got married and had kids. I didn’t have as much time for camping or fishing. I was missing that poetic association I felt with the natural world, and I think it took that hit in the gut from the illness to make me step back and appreciate things and slow down a little bit.

How would you describe your style and what artists have influenced you?

It’s a combination—if you took the Impressionists like Monet and mixed in a little bit of Jackson Pollock, I think I’m existing somewhere in between those. When I started painting again, it had probably been over 12 years since I had really painted or done watercolor, so I’m still kind of young in re-finding my love of painting.

Most of my big things before were all house paint and whatever I could find cheap in mass quantity. So I feel like I’m relearning things, and things are always changing. There are things that I’m known for, whether it’s the splashes or the ink drips, or the energetic messiness to my approach. But I feel like I’m continually changing and finding new influences.

Your style reminds me a lot of Ralph Steadman.

Oh yeah. I love tools. I love implements. I love finding a brush and figuring out what it can do. When I look at an artist like Steadman, who is huge for me, you can see he loves the pen and ink. And I love pen and ink. Because of that we’ve explored what those can do, whether it be swiping it like a sword so it splatters or being able to put out a thick clean line.

I look at an artist like Jackson Pollock; he used sticks, and that’s how he got the thinner pieces. Or Monet and his understanding and noticing of color changes when day turns to dusk, or the way his haystacks look in the winter because of certain color saturations compared to spring. It’s aspects like that that I really love putting in my little encyclopedia in my brain of my implements and approaches. I feel like I’ve been collecting artists my whole life.

Can you describe the process of a typical watercolor piece a bit?

It basically starts with a pretty loose pencil drawing. All the different levels that I go through, I like them to play a role in the end. If I’m doing pencils, at the end I want them to be apparent. So, I’ll be really messy with my pencils, scribbling and circles.

Then I’ll lay down my first layer of watercolor, working from light to dark, then bringing blues in. And after all that’s done, I use a high carbon ink that is super black and thick, and when you lay it down in a line it forms a small wall—it actually has dimension, and I love that.

And then I’ll usually start revisiting with some pencil, revisiting with some watercolor. It’s really building, constantly adding layers and revisiting with other materials. Sometimes acrylic paint will come in if I need something more opaque. Everything starts pretty simple, but then just as the piece grows, it demands things. I just try to listen to it.

How do you know when a piece is done?

It’s the hardest thing to know. When I was starting it was a process. After the pencil was done, then came watercolor, then pen and ink. I felt that nothing else could happen. After I was done with those three levels it was complete.

Now it’s just different. When a piece is done, there’s a kind of internal switch that’s like, alright, turn off now. If I didn’t have to send pieces out, if they didn’t get bought, then they’d be sitting around and I’d still probably touch them off and on.

That makes sense. I always get to a point where I wish that I had stopped at a certain point, because I’ll add something that doesn’t look good. I’ll wish that I had called it quits an hour ago.

I do that with charcoal when I’m doing studies. It happens to me all the time. Having this quality camera on the phone where you can see all the process pictures, I look at them all at the end and think aww, I wish I had stopped there. How do I do that again? Hindsight kind of sucks for the artist.

Do you see any similarities between flyfishing and art? Do they scratch the same itch?

Absolutely. It seems like every time I was in nature with my parents, one of the two was happening. It’s a cliché, but I really do believe in the poetic dance of flyfishing. It’s something that struck me when I was watching my dad do it. I was always like; I wish I could be that graceful. The act of working on something to achieve perfection—I think that’s what connects those two worlds.

When you’re fishing and you catch a fish do you ever look at it and think of the artwork, or vice versa?

Oh yeah. Every day I have the thought that I wish my eyes were cameras. Whether it be how the sun’s coming through the canopy onto the water, or how those shadows look on a brook trout. Even when I wasn’t painting nature, I always had that connection. I remember when I was a kid, just being absolutely amazed and bewildered when I saw my first brook trout.

With my dad in central Massachusetts and Maine, we’d be kind of buried in the forest on a stream that was barely three feet wide, catching these things that you don’t know why they even look like that. It just seemed like there was no reason for there to be these blue dots and red bellies. It seemed so otherworldly to me when I was a kid, and it still bewilders me now, just the beauty of nature and these creatures in our world.

On July 14, Ryan’s daughter had a grand mal seizure and was subsequently diagnosed with epilepsy. The associated expenses have combined with job loss due to the Covid-19 pandemic to create a very challenging time for his family. Ryan is currently selling limited edition prints to defray these costs as well as accepting donations on his website, www.rakart.net. To see more of his work, visit his site or find him on Instagram @rakart_pgh.