Essay

Invisible Restoration

When I was 10 or 12 years old, I watched my father destroy a 19th-century Meissen service plate, a tavern scene with scarlet reticulated edges trimmed with gold leaf. Our house was like a small porcelain museum—a midnight blue Limoges tray with the textured relief of a woman’s face emerging from delicate layers of pâte-sur-pâte; art nouveau Teplitz vases decorated with pastel and metallic-tinted grapes and birds and bats; a hypnotic, cross-legged Meissen pagoda nodder, wrapped in floral patterned robes, whose pale pink tongue slid in and out as its head rocked back and forth. “Be careful” was a constant refrain as I navigated my clumsy growing body through the cluttered hallways. I knew that handling an artifact required the utmost attention and care.

The Meissen plate had once been part of the Smithsonian’s collection, and 20-odd years before, my dad acquired it in a trade after he repaired a crack in it while he was an apprentice conservationist in London. He picked it up from its folding display holder where it sat on a shelf next to another plate with a purple lily—I can’t remember why—and it just slipped through his fingers and shattered into dozens of pieces on the living-room floor. We both stood there, gaping in silence. His shaking hands collected the pieces like they were picking up the pieces of his own heart, and he placed them in a shoebox that he kept in the the back of his closet. Several times over the years I asked him if he was going to fix it, but he just shook his head and sighed.

“It would take too much time,” he said.

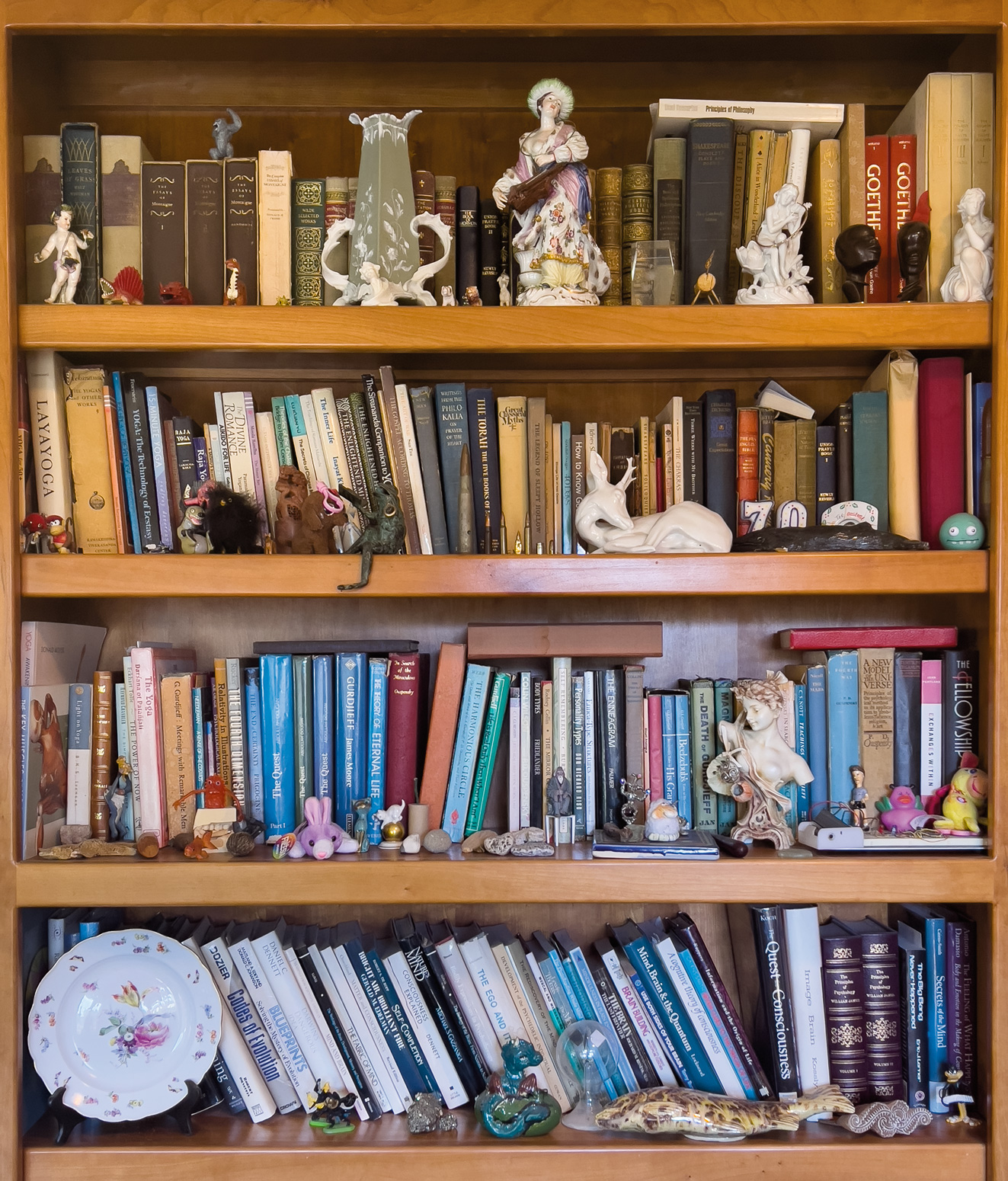

“My father’s bookshelf is replete with three centuries of porcelain displayed among a lifetime’s collection of knickknacks, oddities and curios. For some collectors, the rare and the valuable meld into the sentimental, creating an exhibit of memory and meaning.” Photo: Zack Wohl

The rod was a beloved thing, a birthday gift to myself when I lived in London. I’d handled it—a 4-weight Hardy Zephrus—several times in Farlows before I purchased it. Farlows, at the end of Pall Mall, is London’s last real fly shop. Stocked with three floors of tweed country clothes and high-end tackle, it caters to a discerning clientele from the nearby members-only clubs who can afford access to private trout and salmon fishing. But despite its prestige, the guys who worked there were always willing to discuss less-esteemed pursuits like reservoirs, pike and carp with an American who was confused about fishing in the United Kingdom.

In Farlows, I bounced the rod in my hand to test its weight and faux cast it to test its action. Its yellow-streaked, moss-green reel seat looked handsome at the end of the olive rod blank, with dark wraps and titanium stripping guides. The cigar-shaped cork was a light blonde color, and the smooth taper toward the end set nicely into the flesh of my pinky and ring fingers. I paired the rod with a Hardy Duchess reel that had a knurled palming edge, lacquered wooden handle and gold rivets. I fished often with the rod and doted over it every time I slid it from its black cotton sleeve.

A few years later I brought the rod to the McCloud River, hidden just south of California’s Mt. Shasta in a steep canyon covered with incense cedars and ponderosa pines. The river’s deep emerald waters cascade over a bed of rounded boulders. Umbrella plants, with their clusters of dinner-plate-sized leaves, droop over the shoreline. Wherever they can find relief from the current, grasses spring up from rocks in the middle of the river. In the fall, the yellow and red of the black oaks and western dogwood come into sharp relief against the evergreens, and bald eagles and great blue herons pass overhead. The canyon is cool and shady, and the rapid flowing water is ice cold.

The first morning of the trip I worked across the river with the Hardy, casting to converging currents and submerged structures before I landed my flies where a crystalline hunk of rock on the far bank diverted the river’s flow, accelerating it into a seam beside a pocket of soft water. Nothing. I tried again and watched my white strike indicator as it bobbed along. It dipped under. I lifted my rod to set the hook; the trout felt heavy as it pulled line out into the current. I swung the rod to my side to coax it away from the rapids at the end of the pool then saw its silvery silhouette as it ran hard. It was a good fish.

“Hey Kristin!” I hollered to my wife who was fishing upstream. “Got one!”

Eventually, I muscled the fish toward where I stood, balanced on slick stones with the water making a wake against my legs. I dove at it with my net but couldn’t close the last two feet, so I reached impatiently for the leader. The tension in the line went slack when the tippet snapped against the weight of the fish. It fell backward and disappeared into the rapid, and I cursed and flogged the water with my rod.

“Zack! Stop that!” Kristin yelled. Her voice barely carried over the rush of the water.

I had witnessed and participated in a few river thrashings over the years and when I swung my rod at the river, I had expected the forgiving surface of the water to absorb my sudden rage. But there it was, a clean break revealing the circle of a hollow tube on the tip side and splintered carbon fiber on the other. I lifted the broken rod. Its severed tip hung on the line.

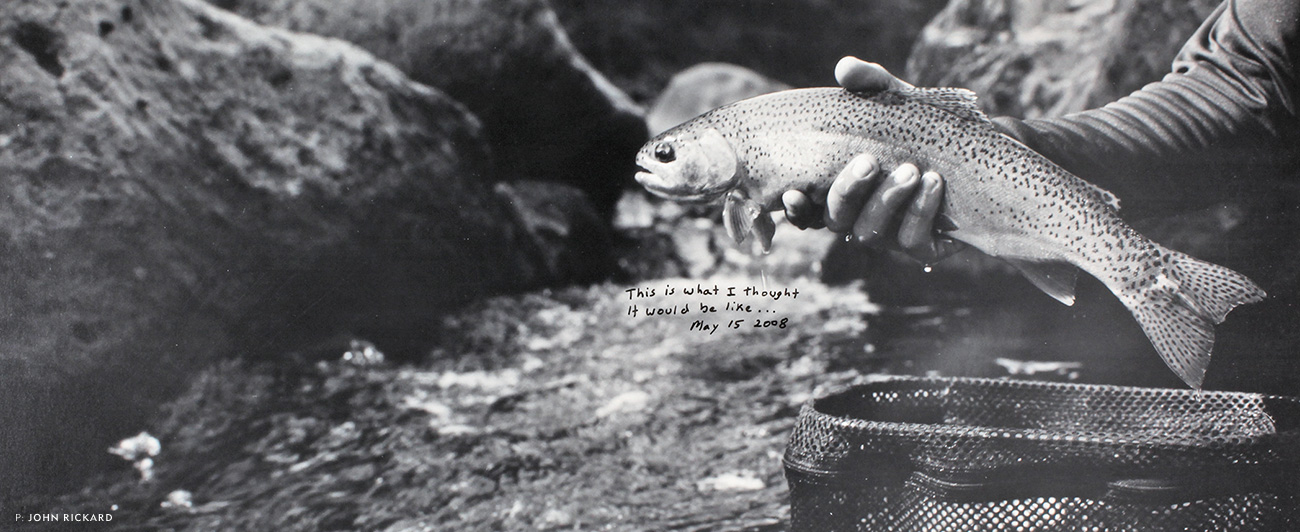

When the façade not only cracks, but also explodes. Photo: Tim Romano

When I returned the rod for warranty repair, I listed the reason as “Lost Big Fish,” which I considered a factually correct root cause. One skilled fly caster I know told me that whenever he breaks a rod, he sells it as soon as he gets it fixed. He maintains it never casts the same again, its action altered by the replacement section, and he would rather unload it and move on than be stuck with a rod that was an inferior version of its former self. Casting the revived Hardy, I was unsure if I could feel a difference. It still flicked a tight loop off the tip and loaded evenly. But when Hardy returned the rod to me, they didn’t send a ferrule stopper—a tiny machined-aluminum plug meant to keep dust out of the rod—for the new tip section. It felt like the rod was somehow incomplete, even if only in some small, superficial way.

When my father repaired a piece of porcelain, he could complete either an invisible or museum restoration. Bent over his workbench beneath bright lights, he first roughed up the exposed edges of a broken piece using sandpaper so fine it didn’t deserve the name. Peering through a magnifying headset, he then brushed on a thin layer of epoxy. His certain, practiced hands fit the pieces together as the epoxy began to harden. Tape or a weight or a jig constructed using odd objects like books or pens or rocks held the pieces while the epoxy set enough to fire everything in a warm oven, completing the chemical process. He used sparing strokes again to sand any excess adhesive, smoothing the seam. A museum restoration stopped there. The break, left visible, became part of the piece’s provenance, history and character.

To complete an invisible restoration, he went one step further and committed an act of art—of deception—by painting over the break. He mixed paints to match the colors of a piece before airbrushing on the mimetic tones. Once the paint had dried, if the pieces fit and the colors blended, only the most sensitive eye could detect his work. While some people may prefer an invisible restoration for a piece in their private collection, hidden damage is less desirable, and if found impacts the value of a piece more than a visible repair. Like most things, it is better to be honest about imperfections and blemishes.

The evidence left by trauma always varies. Since I got the Hardy back, I’ve fished it a couple of times and caught a few trout, but mostly I’ve kept it in its case, away from the water. Remembering the rod’s break reminds me too much of the times when I cracked.

The Upper Sacramento River, just west of the McCloud, was pronounced dead in 1991. Downstream from a stretch of shady pocket water a train car derailed, tumbling from a curved bridge and spilling 19,000 gallons of weed killer into the river. All along the river fish huddled near shore or beached themselves on shallow gravel, trying to escape the toxic plume that would eventually suffocate them along with salamanders, insects, crustaceans and other creatures. The poison didn’t stop at animals, killing algae, aquatic plants, cottonwoods, alders and willows along the river. People filled trash bags with brown and rainbow trout that had washed onto the banks. When officials closed the water to fishing, it must have come as a strange pronouncement—all life in the river was already gone.

It would take years before new stocks of fish could be planted and even longer before they would return to their previous numbers. A quarter-century later, when I first fished it, I would not have suspected the catastrophe had I not read about it. Relieved by cool water against my legs during sweltering September days, I drifted nymphs through riffles and pools and caught 10- and 12-inch rainbow trout. The locals told me it was never quite the same—the insect hatches in the evenings weren’t as thick and the crayfish and salamanders never came back—but considering the extent of the damage, that life returned at all was a miracle.

Like a piece of ceramic, a river is fragile and given to destruction if mishandled. We can leave it barren with a single catastrophe or wear away at it with generations of misuse, but unlike porcelain, fixing it is a matter of years and decades. When we help the natural world to heal, we are doing it as much for ourselves as for those that will come later. The fishing will never be what it once was, but if we are farsighted and persistent, we can find a different equilibrium.

A view from Brandstetter’s Ranch, CA of a passenger train on the Cantara Loop in Siskiyou County. Date/photographer unknown. Photo: Courtesy of the California History Room, California State Library, Sacramento, CA

For me, fishing is not relaxing. Before catching any fish there is a rising tension. It is the tension of expectation, not unlike courtship or gambling. When I catch a fish, I am overcome by relief, like the experience of lightness after setting down a heavy pack after a long hike. If I fail, there is only the continued acidic discomfort of pulsing cortisol. All I can count on is the pleasant numbness of physical exhaustion, which comes from balancing and wading in the river, scrambling up and down loose and rocky banks, and casting to where I hope to find my quarry.

The more I want the fish, the less I enjoy the fishing. Enjoying the fishing requires getting lost in the process—the river’s surface that shifts like melting glass, the midges hovering in uninterpretable patterns, the infinite shades of light blended with shadow, the constant white noise of the current. The fish becomes a totem rather than a goal, a symbol that emerges through integration.

In those interludes of transcendence, the parts of us that are marred and hardened are subsumed by the present. Presence is a means to free ourselves from the cycle of trauma and healing, damage and restoration, by giving us a glimpse of a different state: just being. Then, for a moment laid bare, we can accept and begin from what and where we are.

Another day on the McCloud, having sweat through my shirt and steamed in my waders during a sun-soaked morning, I napped on the riverbank then sat with Kristin in a shallow, chilly pool shaded by a lone tree. Once the sun lowered beyond the canyon wall, I hooked a big rainbow at the end of a long run and tussled with it in the late-afternoon shade. I reached for my net once I had backed the fish into the shallows. I inched toward it, keeping side pressure with my rod—an old 6-weight Winston that I had chosen instead of the Hardy—as I closed the gap. It shook its head, but I kept pressure. It was just at my feet. It shook again, the tension left the line and the fish vanished into the dark blue bottom.

“Fuck,” I rumbled, raising my rod. But I stopped and lowered it to my side.

A little later Kristin and I moved downriver and descended a rocky outcropping above a quick current. As we came to the edge of the water, we saw a fish rise along a bubble line. Then we saw another. There was only one good perch on the rocks, so we took turns fishing. Kristin cast and her fly drifted past us. She cast again a little farther out.

“Got him,” she said, raising the rod.

She played the fish while I skipped down the rocks to help land it below. I laid on my belly to reach the water, stretched my arm and scooped the fish into my net. It was a thick rainbow with carmine gill plates and even black spots extending down past its pink lateral line. But its jaw on one side was deformed, so the upper part was dislodged and stuck to the bottom, preventing it from closing its lips. I couldn’t tell if the disfigurement was congenital or from an old wound, but it hadn’t kept it from eating.

“You caught the ugliest fish in the river,” I said with a grin, lifting the fish up for a moment. Kristin beamed. It was a good fish, imperfect yet beautiful, like my dad’s porcelain collection—broken and healed, damaged and restored, marked by scars and rough edges, but also made complete by them.