Conservation

ON BREACHING THE SNAKE RIVER DAMS

First published in Volume 15, Issue 1 of The Flyfish Journal

The Nez Perce call the river yáwwinma, meaning place of cold water. Non-Indigenous people refer to it as Rapid River.

It’s the only stream Congress ever designated a Wild and Scenic river exclusively because of its water quality. Even in August anglers wet-wading its headwaters suffer numb feet. The steep forested canyon and its rock formations block out the sun for much of the day, leaving the cold-water temperatures intact and the fish thriving. The rainbows come mostly in two sizes—small and smaller. I’ve never caught one over 10 inches, but unlike many rainbows elsewhere with their mongrel genetics, these little Columbia Basin redsides qualify as true natives with an immaculate pedigree stretching back to the end of the Miocene epoch, five million years ago. A few wild steelhead, genetically indistinguishable from the small resident trout, still return to spawn each year. Some fisheries biologists speculate, based on its V-shaped structure, that the upper yáwwinma may once have been primarily a steelhead stream. Salmon, they say, prefer flatter, more U-shaped river valleys like the lower river’s. Still, the true trophies in the upper river are the resident bull trout, a threatened species that averages 12 to 18 inches. Usually, some wild adult summer Chinook also slip past Rapid River Fish Hatchery, located about four miles above the confluence of yáwwinma and the Little Salmon River. Only the rugged and remote 27.8 miles of the roadless yáwwinma headwaters, accessible solely by trail, qualify as Wild and Scenic. And they are, indeed, spectacular.

above Nez Perce (Nimiipuu) tribal member Brian Holt gaff-hook fishing for spring Chinook on Rapid River, a tributary of the Little Salmon River. Photo: Ben Herndon

But it’s the Rapid River Fish Hatchery and the lower four miles of the river near Riggins, ID, that interest me most. This short stretch flows away from a paved county road, past two subdivisions of houses, and beyond angus and Hereford cattle in fenced pastures full of whitetail deer until it reaches a large manmade pool where salmon congregate at night. Here, each morning through April, May and June (and rarely into July), hatchery workers net each salmon, inspect it for disease, carefully measure and weigh it, transfer it to a tank truck, and then transport the morning’s catch another mile upriver to a holding pond. The Nez Perce Tribe now owns two parcels of land on the lower river—one parallel to Highway 95, the other a large, verdant, rectangular flat with a gated fence just upstream.

When the Chinook runs provide enough fish for ceremonies, sustenance and trade, this second piece of property morphs into a temporary Nez Perce village of teepees, tents, small camper-trailers and pickup trucks. Children play games on the grass while elders gossip or roast salmon fillets on sticks above small blazes. A soft wind air-dries razor-thin strips of orange Chinook flesh hanging from branches of bushes and small trees. At night, some men continue fishing, but most people stay in camp eating, watching campfires, trading rumors and news of the day, telling stories and singing songs in English and Nez Perce to the beat of a hand drum. Cell phone service is either extremely poor or nonexistent.

In good years, I’ve seen several fishermen with dip nets and gaffs pull out 50 or more fish weighing between seven and 15 pounds in little more than an hour. I’ve also seen a “double” hit of salmon in a single dip net pull a fisherman into the river and watched fisherman and dip net go floating off down the Rapid toward the Pacific 500 miles away (much to the astonishment of those line-fishing shoulder-to-shoulder just downstream). A few years ago, this lower section of river and the two parcels of land qualified for the National Register of Historic Places as Idaho’s first (and so far, only) traditional cultural property. I felt honored to coauthor its nomination. The location has a storied past, one that is intimately tied to the ebb and flow of salmon runs in the years since four dams were installed on the lower Snake River in the 1960s and ’70s. In June of 1980, a long-standing conflict between the State of Idaho and Nez Perce fishermen at Rapid River turned physical. To this day, some tribal members call it the Second Nez Perce War.

above The last of the fall colors, November 2021. Kyle Lerch releases a beauty on a Snake River tributary. Photo: Ben Herndon

“We’re sitting on a powder keg,” Evan Parrish, the hatchery superintendent, told a New York Times reporter in 1977. “There are enough crazy cowboys and loggers around here for there to be an explosion.” In the nearby town of Riggins, ID, (pop. 588 at the time) residents like general store owner Bill Pottenger tried to light the fuse. When asked if there would be trouble on opening day of salmon season that spring—the river had been closed to salmon fishing the previous three years due to low returns—Pottenger said, “I sure hope so! I’m going to encourage fishermen I know to run the Indians off the river.” Yet somehow, with a limited salmon season opened again to non-tribal members, a precarious peace prevailed, although reporters observed that both the townspeople and the Nez Perce “carry guns.”

Three years later, in 1980, after yet another of the poorest Chinook returns in the hatchery’s history, Idaho imposed still another closure, but this time they included the Nez Perce. Then as now, many blamed the tribe and their fishing methods for the poor fish returns.

above left to right

“Little Goose Navigational lock. While access is limited, it was visually interesting to explore and photograph these massive structures during a road trip in September 2022.” Photo: Copi Vojta

“Little Goose Dam. Though several folks were fishing for salmon right below the dam, the only thing caught was a smallmouth bass—a nonnative invasive thriving in the warm, stagnant waters around the dams.” Photo: Copi Vojta

Eric Crawford, Kyle Smith and Will Poston (L to R) juggle fly rods and dogs during an evening fishing session on the Clearwater River, ID. In fall 2022, Trout Unlimited hosted a rendezvous to educate others about the lower Snake River dams, discuss various issues surrounding the proposals to remove them, and get a bit of steelhead fishing in. Photo: Copi Vojta

“We knew we weren’t the reason the fish were being wiped out,” Virgil Holt Sr., a 29-year-old tribal fisherman, said at the time. “It was the dams and the management that were hurting the fish runs. We weren’t responsible for either.” On the 25th anniversary of the standoff, the late Nez Perce elder, Elmer Crow, told a small crowd, “The State had snipers up on the hill ready to shoot us. Unbeknownst to them, we had snipers on the hill behind their snipers.” Despite heavy harassment, the Nez Perce fishermen persisted, vowing to fight to the death to preserve their 1855 treaty rights. One by one, day after day, they were ticketed, arrested and frequently jailed. “If even one person on either side had done something crazy,” Holt recalled, “Rapid River would have run red [with blood].” Instead, although enforcement officers carried pistols and clubs, physical violence was limited to a few brutal scuffles.

Two years later, in 1982, Judge George Reinhardt threw out all charges and reaffirmed the tribe’s treaty rights to fish in “all their usual and accustomed places” on and off the reservation regardless of the state’s actions. By then, of course, the Dalles Dam (1957) had long since silenced Celilo Falls, the oldest continually inhabited site in North America and the greatest of all tribal fisheries. The four Lower Snake River Dams—Ice Harbor (1962), Lower Monumental (1969), Little Goose (1970), and Lower Granite (1975)—had drowned countless other tribal fishing sites and reduced the Snake and Clearwater salmon and steelhead runs to mere fractions of the hundreds of thousands of fish that once returned to the rivers.

above “A full view of Little Goose Lock and Dam. The brutal contrast between the loud, buzzing monolith and the rolling golden hills of the Palouse took time to get used to. Imagine the recreational opportunities for anglers, boaters and sightseers through this stretch if the Snake River were allowed to run free again.” Photo: Copi Vojta

It’s hard to imagine a time before the dams. When I arrived in Lewiston, ID, in 1984, the Lewiston Dam had been gone for a decade and wild steelhead had begun to reestablish themselves in the upper Clearwater and some of its tributaries. So, I think, had Chinook. Still, though adult steelhead returns seemed to oscillate dramatically, the Dworshak National Fish Hatchery was releasing over a million steelhead smolts a year to supplement wild stocks as mitigation for the construction of another dam, Dworshak, in 1973. The first time I saw that gray behemoth, rising 717 feet into a bluebird sky, I nearly swerved into an oncoming pickup. Turns out, Dworshak is the tallest straight-axis concrete dam in the western hemisphere. That construction of that ecological disaster happened on the watch of Governor Cecil Andrus, a passionate conservationist, fellow angler, and former Secretary of the Interior under President Carter, baffled me. Dworshak Dam killed 54 miles of the lower North Fork of the Clearwater River. In addition to blocking passage to the spawning beds of arguably the finest population of large steelhead in the world, flooding 17,000 acres of prime winter range for elk, and violating, yet again, the Nez Perce Treaty of 1855, construction killed eight men. When, at last, I got the chance to ask Andrus in person how he could ever have consented to the construction of that monstrosity, he flushed as red as a stoplight. “It was a done deal before I could stop it,” he hissed, “but by God I vowed it would be the last one. And it was.”

But the damage, of course, had been done. Now we face an urgent crisis of extraordinary magnitude: whether to allow our magnificent wild salmon and steelhead to go extinct or try to save them by removing the lower Snake River dams. Oddly, no well-informed person or government agency disagrees that breaching the dams would produce the highest likelihood of saving the fish (with ripple effects that include providing a boon to southern resident orcas, which rely on migrating Columbia Basin salmon for food). As early as 1999, National Marine Fisheries Service studies determined that the most risk-averse action to recover the fish would include dam breaching. They went even further by declaring that, for Endangered Species Act-listed Snake River fall Chinook and steelhead, “dam breaching by itself would likely lead to recovery.” In 2002, after seven years of study at a cost of $33 million, the Army Corps of Engineers agreed that breaching the dams had the highest probability of meeting the government’s salmon survival and recovery criteria and that other “reasonable” alternatives would be slightly worse than doing nothing. So that’s what they did—almost nothing.

above left to right

Steelhead anglers new and old gather on the Clearwater River, some with decades of steelheading experience, others learning to cast two-handed rods for the first time—all coming together with Trout Unlimited in support of breaching the lower Snake River dams. Photo: Copi Vojta

A view of the storied Clearwater River, one of the Snake’s many significant salmon- and steelhead-bearing tributaries, near Lenore, ID. Photo: Copi Vojta

Ice Harbor Lock upstream of Washington state’s Tri-Cities. Photo: Copi Vojta

Over the course of 14 years, the Corps wasted about $4 billion of rate- and taxpayer money on hardware improvements and transporting smolts around the dams. Independent scientists have pleaded the case for breaching for 50 years. In February 2021, 68 of them signed a letter to Pacific Northwest governors, members of Congress and policymakers, calling for dam removal to protect salmon and steelhead from extinction. I suppose we all know how many times most politicians read their mail personally: less than once. Still, when a Republican from one of the reddest of the blood-red states becomes the first-ever and only congressperson to propose a bill to remove the dams, restore the runs and fairly compensate all parties for any losses—well, maybe it’s time to rekindle hope for the species Homo sapiens, the only one of several species grouped into the genus that is not extinct. Make no mistake: As the threat of climate change continues to remind us, despite our billions, we, too, are an endangered species. The fate of humans and the fate of wild salmon and wild steelhead is the same.

Those who favor the status quo argue that the “pollution-free” electric power the dams produce is essential to the region. Yet the four dams were never built to produce electricity. They were built for navigation. In fact, their 32 aging generators (all in need of imminent repair or replacement) produce shockingly little of the region’s juice (3-4 percent). And none of that electricity comes carbon free. Reports in 2013, 2016, 2017 and 2020 by Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) and its affiliates concluded that the reservoirs behind the dams now annually produce significant amounts of methane, the equivalent of 86,053 metric tons of CO2.

above left to right

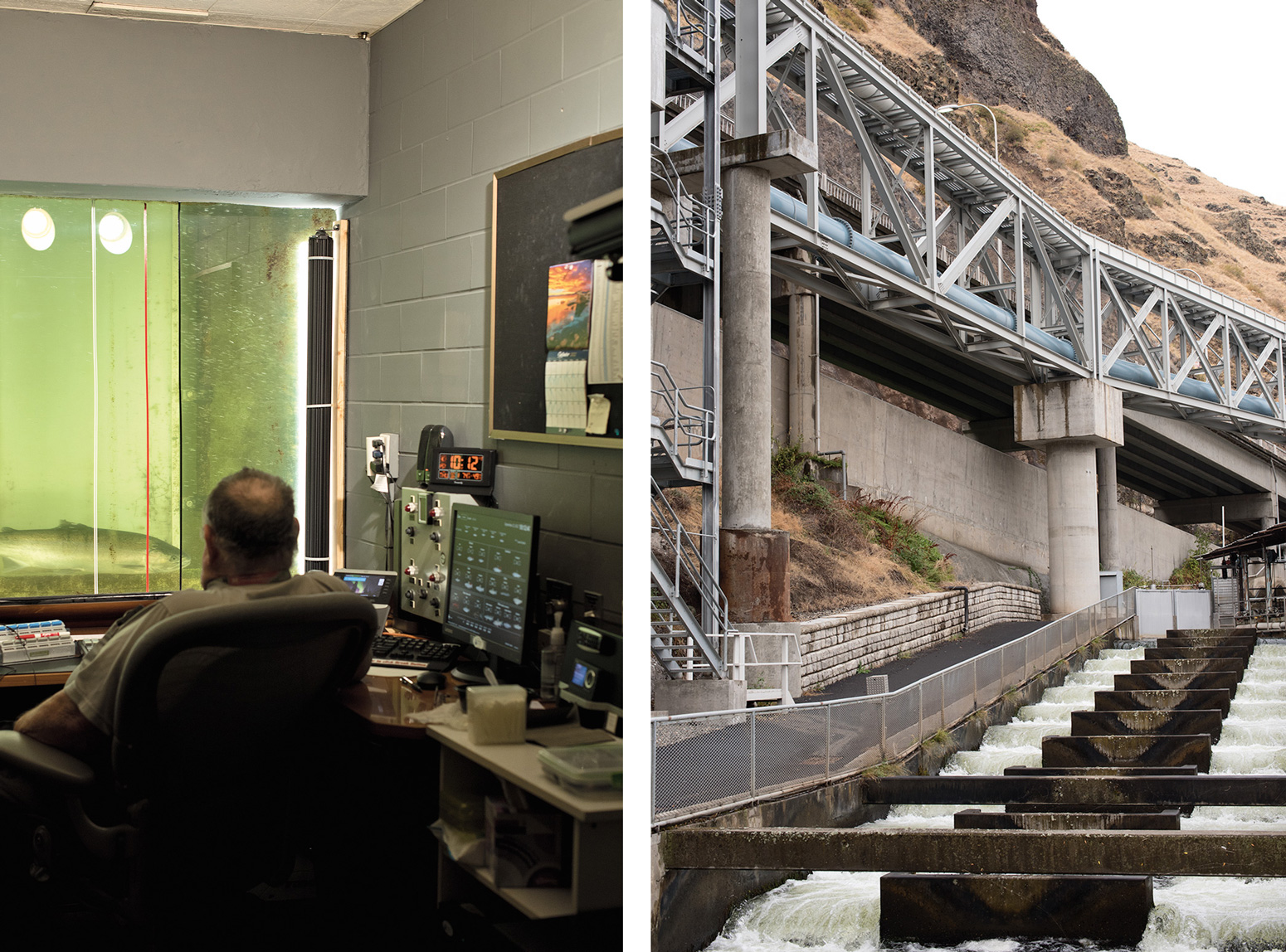

“A steelhead passes through the counting window at Lower Granite Dam. During our Trout Unlimited rendezvous a good storm came through, so the group took that opportunity to visit Lower Granite. We saw carp, northern pikeminnow, Chinook, steelhead and even a walleye through the viewing windows.” Photo: Copi Vojta

The Lower Granite Dam fish ladder. Photo: Copi Vojta

Water temperatures behind the dams, particularly in the summer and early fall, can reach 71 degrees. In 2015, 99 percent of returning sockeye—an estimated 250,000 fish in the Columbia and Snake rivers—perished from superheated water in the reservoirs. (Sockeye are particularly vulnerable because they migrate during the hottest part of the summer. Temperatures above 68 degrees weaken steelhead and other salmonids too, making them lethargic and more susceptible to disease and predation.) The smolt-to-adult (SAR) return rate for wild Snake River steelhead is currently 1.4 percent; for spring and summer Chinook, 0.7 percent. Both fall well below the 2 percent SAR required for survival, to say nothing of the restoration goals of 2-6 percent set by the Northwest Power and Conservation Council. For the runs to grow, we need an average of 4 percent. To predict how the Snake River runs might fare in the wake of dam removal, we can look to the SARs in Oregon’s John Day system: 5 percent for steelhead and 3.6 percent for salmon. The John Day is the longest undammed tributary of the Columbia and the last major tributary salmon and steelhead encounter before arriving at the Snake. Such evidence suggests that John Day fish prove more successful because they have four fewer dams to navigate than the Snake River fish (though, notably, those John Day fish still navigate three dams on the main stem Columbia).

above left to right

Nez Perce (Nimiipuu) tribal member Tracey Jackson poses for a portrait while gaffhook fishing for spring Chinook on the Rapid River. Photo: Ben Herndon

Nez Perce (Nimiipuu) tribal member Tracey Jackson holding harvested spring Chinook at his camp on a traditional fishing site at Rapid River.Photo: Ben Herndon

Opponents also complain that breaching will hurt farmers and cost jobs, but research scientist Daniel Malarkey, who oversaw the Energy Office of the Washington State Department of Commerce before becoming a fellow at Sightline Institute and a senior research scientist at the Sustainable Transportation Lab at the University of Washington, has studied the economics of breaching as carefully as anyone. In a series of three analytic reports, he made his case for removal. In a 2019 article for the Sightline Institute—a Pacific Northwest think tank focused on sustainability—he proved that making Snake River irrigators whole, which Simpson’s plan does, would cost surprisingly little. These farmers grow mostly whole foods—potatoes, corn, wine grapes, apples and other fruit—on about 50,000 acres, with water diverted from McNary Dam. Farther upstream, at Lower Monumental, Little Goose and Lower Granite dams, irrigation plays no role in crop production. About 90 percent of all barges that pass through the locks at all four dams carry dry-farmed wheat harvested from corporate holdings, most of them government-subsidized. Malarkey points out that the federal government spends $21 million dollars per year operating the locks at the four Snake River dams. Put another way, the feds spend one dollar so the grain shippers can save 30 cents. “Better,” Malarky says, “to pay the grain growers the 30 cents directly.” If the dams were breached and the feds shifted their subsidy from river barges to trucks and trains, “growers’ transportation costs need not increase at all.” As for jobs, Malarkey concludes that breaching will add to, not subtract from, jobs in the region.

above left to right

The Clearwater River and Lenore Bridge. Photo: Copi Vojta

A scar of concrete at Lower Granite Dam. Photo: Copi Vojta

“Honor the Treaties, Breach the Dams.” A billboard along U.S. Highway 12 outside of Lewiston, ID, expresses the Nez Perce tribe’s point of view toward the lower Snake River dams. Photo: Copi Vojta

With taxpayers subsidizing transportation on the Lower Snake at the rate of at least $42,000 per barge load and ratepayers having expended over $17 billion on failed mitigation, there is surely a sound economic argument to be made in favor of breaching. Linwood Laughy, an indefatigable researcher who has studied the situation for two decades, summarizes his case this way: “Is anyone willing to bet…aging [dam] infrastructure will require less-costly repairs [in the future]? That freight volume will dramatically rebound [from a 40 percent long-term decline]? That the United States will fail to honor treaties backed by the U.S. Constitution? That the Endangered Species Act and Clean Water Act will be ignored in the courts?” Congressman Simpson estimates the cost to breach the dams, compensate stakeholders, and create new infrastructure to be about $33.5 billion, with breaching to begin in 2030. If we do not breach the dams, he says plainly, “we are condemning Idaho salmon and steelhead to extinction.”

above Lower Granite Dam panorama. Photo: Copi Vojta

Although his plan immediately drew whines and yowls of objection from the usual suspects, it also spurred debate and refocused media attention on the issues. Washington state governor Jay Inslee and senator Patty Murray subsequently launched their own formal study. The Nez Perce backed Simpson’s plan almost immediately because, they said, it follows science and protects communities that depend on the river. A dozen other Columbia Basin tribes, including the Shoshone-Bannocks, Colvilles, Spokanes, Yakamas and Umatillas, soon followed. They began seeking a dialogue to advance discussions with various agricultural, energy and business entities, as well as with officials from the White House. While doing so, the tribes also pointed to the largest dam removal project in the world, the elimination of four dams on the Klamath River that Congress rejected but that is now in progress. Last March, President Biden stopped short of endorsing breaching but promised to work with Congressman Simpson, Senator Murray and the region’s tribes to protect salmon in the Columbia Basin.

above left to right

The Red Shed Fly Shop in Peck, ID. “Poppy” Cummins, a local legend in the spey fishing and steelhead worlds, opened the shop in 2002. The floors are plywood, so you don’t have to worry about mucking them up with mud or studs if you stop in to talk shop between steelhead runs. Photo: Copi Vojta

Grain elevators and storage silos along Lower Granite Lake outside of Clarkston, WA. Photo: Copi Vojta

“Jerry Meyers, retired outfitter, longtime Idaho steelheader and conservationist, kept us entertained with his stories and was a patient instructor on the river, helping me practice a Snake roll cast. In return, I gave him one of my home-tied steelhead muddlers. I hope he’s had a chance to fish it.” Photo: Copi Vojta

A non-Indigenous person fishing for salmon fishes mainly for sport. As my late friend and former neighbor Horace Axtell patiently explained to me, a Nez Perce who fishes for salmon is practicing traditional religion, although Horace would probably never call it that. Instead, he’d prefer the terms wáashat or waasaní or Seven Drum. He’d call fishing a life way that requires always honoring the Creator. He might even say while fishing that he and the fish are dancing. Among the Nez Perce, salmon has always figured as the most prominent and common food. It’s also a sacred food, a gift from the Creator. Established custom favors the presence of salmon at all Nez Perce ceremonies, not just in the longhouse on Sundays but at birthdays, naming ceremonies, giveaways, weddings, funerals and tribal and Christian holidays. (Some Nez Perce find no contradiction in practicing both wáashat and Christianity.) Regardless, salmon are inseparable from Nez Perce identity. We are Salmon People! the Nez Perce often remind non-Indigenous people.

above Lower Monumental Dam panorama. Photo: Copi Vojta

As far as I can tell, absent from the Nez Perce and other tribes is what Wallace Stegner called “that hard determination to dominate nature” that he and other historians recognized as “part of our Judeo-Christian heritage.” As a classic example, Stegner quoted the Mormon high priest John Widtsoe, writing during the late 19th-century irrigation campaigns: “The destiny of man is to possess the whole earth; the destiny of the earth is to be subject to man. There can be no full conquest of the earth, and no real satisfaction to humanity, if large portions of the earth remain beyond his highest control.”

Here I can only echo Stegner in saying, “That doctrine offends me to the bottom of my not-very Christian soul.” It’s the same dogma of conquest, of course, that “tamed” the Colorado River with 15 dams, one of them—Hoover—touted in its day as a true “wonder of the world.” Anybody who reads the news knows the reservoirs behind the Glen Canyon and Hoover dams now approach “dead pools,” the level where water can no longer flow downstream. In those dead pools and the thousands of acres of muck and mud behind them, we may see the future of the Lower Snake River and its dams if we leave them in place. Alternatively, we can choose to let the Snake loose to twist and writhe again for 143 miles, granting endangered anadromous species access to additional hundreds, if not thousands, of miles of unspoiled Idaho habitat, much of it in wilderness areas like the Middle Fork of the Salmon River. But without breaching there is no chance whatsoever of lowering water temperatures or creating safe passage for salmon and steelhead. Without breaching, these beautiful and imperiled fish are doomed.

above Reid Curry pushes through hazy skies and mellow steelhead runs on a multi-day river trip in a Snake tributary that would greatly benefit from dam removal. Photo: Copi Vojta