Adventure

Recording Sherbro Island

April ’92 in Sierra Leone

The body of water between Bonthe at the eastern end of the island and the mainland, called Sherbro Strait, is a record tarpon factory.

In April 1992, Sierra Leone was in the beginning stages of what would become a decade-long civil war. With the aid of then-president of Liberia Charles Taylor (who is currently serving a 50-year sentence in the United Kingdom for various war crimes committed during that war), rebels in eastern Sierra Leone rose up against President Joseph Momoh, firing the opening volleys of what would eventually become one of the most brutal civil wars in African history.

But that April, the war that would come to be known for blood diamonds and child soldiers hadn’t yet metastasized into full-blown conflict throughout the country. Freetown, the capital located on the western coast, was a sort of “Club Med” for European tourists, according to Pierre Affre, champion fly caster, angler and filmmaker. Affre had fished for tarpon in Sierra Leone the previous spring after being tipped off to the massive fish found there; in 1992 he returned with a few record chasers, namely Billy Pate and Tom Gibson (a conventional angler), and a young photographer from the Pacific Northwest named Brian O’Keefe. Ironically, given the record-setting pedigree of the assembled group and their deep roots in the Florida tarpon fishing scene, it would be O’Keefe who would leave Sierra Leone with his name in the record books.

above G.E. (Ged) Fleming with some Sherbro Island locals and the 242-pound, world-record tarpon he caught in 1992; it was the largest tarpon landed on the trip, but probably not the largest hooked. The locals, after seeing this fish, estimated that they had seen 300-pounders. The man with a semiautomatic rifle was hired for protection. Photo: Brian O’Keefe

O’Keefe, at the time a 37-year-old flyfishing sales rep and professional photographer from Oregon, had been “hired” (he had to pay his own way) by the editor of a saltwater-centric flyfishing magazine to document the trip, which nominally revolved around Pate’s quixotic (in retrospect) efforts in Sierra Leone. Author Monte Burke’s recent book about the chase for world-record tarpon, Lords of the Fly, recounts Pate’s simple arithmetic where Sierra Leone was concerned: “Pate had heard that the tarpon in Africa grew to immense sizes, perhaps even bigger than the ones in Homosassa, [Florida]. Armed with his twenty-pound tippet, he believed he could set the new world record there.”

One year prior, in April 1991, an angler named Yvon Sebag had caught a 283-pound record tarpon on conventional tackle near Sherbro Island, a low-lying, wedge-shaped piece of land that sits about midway between the northern and southern extremities of Sierra Leone’s Atlantic coastline, tucked among shifting sandbars and marshes near the mouths of two rivers. The point of the wedge, a few degrees north of the equator, aims west, directly at South America; the wedge’s back lies 32 miles to the east and is home to the island’s only city and port, Bonthe. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the island served as a resettlement location for Africans who had escaped or otherwise found freedom from slavery in America. Rustic villages dot the shoreline, visible as small, neat clusters of squares on satellite maps.

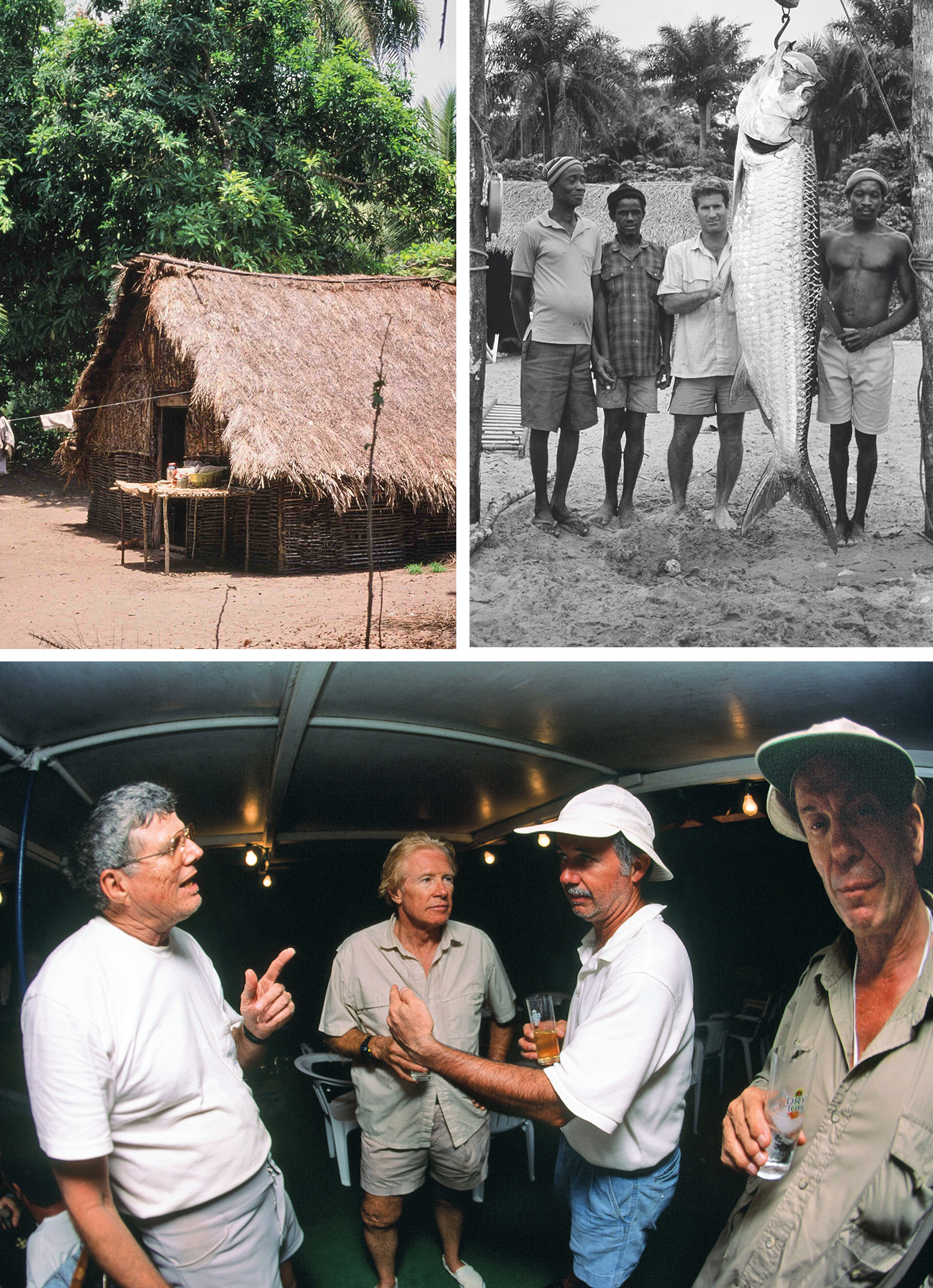

left to right “The Sierra Leone Civil War lasted for 11 years. We encountered soldiers and makeshift roadblocks, and at times paid bribes for passage; yet there were a few beach resorts operating as normal. It was confusing and at times dangerous, and in the pre-internet days we didn’t really know what we were getting into.” Photo: Brian O’Keefe

“The closest village had a population of about 200 people. The locals ate the tarpon we killed for science.”Photo: Brian O’Keefe

The body of water between Bonthe at the eastern end of the island and the mainland, called Sherbro Strait, is a record tarpon factory. Of the 24 Conventional Tackle Line Class records currently held for tarpon (12 each for men and women), nine of them were set at Sherbro Island, with four others set in nearby Guinea-Bissau and Congo. Indeed, it would seem that as soon as the Sherbro Island fishery was discovered by the conventional tackle crowd in ’91, there was no looking back. With the exception of a Florida-caught fish from the mid-’70s, and a Venezuela catch from 1956, every plus-200-pound tarpon in the International Game Fish Association conventional tackle record books has been taken in West Africa, with the majority taken at Sherbro.

So it is noteworthy that, of the 14 flyfishing record classes (seven each for men and women), only a single (now-retired) entry comes from Sherbro. The summary of the entry, which was retired in 2001, reads, in part: “Line Class: Tippet 20 lb. Weight: 187 lb. 6 oz. Location: Sherbro Island, Sierra Leone. Catch Date: 09-April-1992. Angler: Brian O’Keefe.”

clockwise from top left

“The closest village, a true wilderness outpost, consisted of 100 percent organic hut construction: mats, palm-frond roof, wood poles and twine. The people lived off the land and water. One night, they entertained us with a big fire and dances.” Photo: Brian O’Keefe

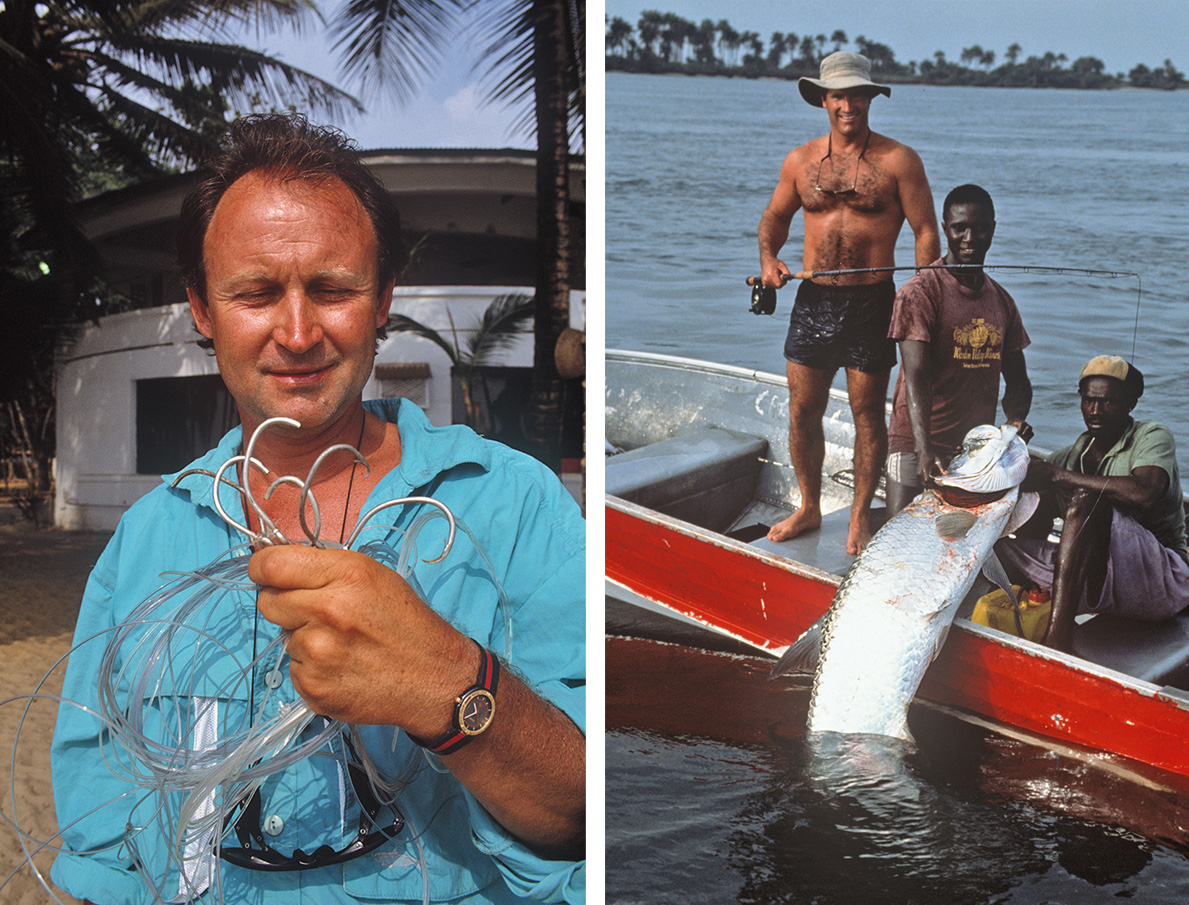

“One of the missions on this trip was to dissect five different sized tarpon for science, small to large, to determine their age and growth rate. We brought liquid nitrogen, a common industrial and scientific coolant, to freeze the otolith bones.” Brian O’Keefe and local fishermen with O’Keefe’s 187-pound tarpon. Photo: Courtesy Brian O’Keefe

“From left to right: Tom Gibson, Billy Pate, Ged Fleming and an unknown angler in the middle of what was no doubt a deep-dive discussion of all things tarpon—the topic of choice most evenings. The lights in this common area on the ship were accidently left on one night, and in a place with no artificial light, this attracted an inch-thick carpet of insects by morning. One of the locals showed us which ones were edible.” Photo: Brian O’Keefe

O’Keefe has made it clear he had no particular interest in records. He was there to take pictures and, since he’d had to pay for the trip himself, hoped to get a little fishing in of his own. Though they only planned to be at Sherbro for five days or so, he spent the first few days of the trip shooting film, fishing gear and fly rods from shore and generally staying out of the way of Pate and the others as they went out each day searching for records in a pair of Boston Whalers. As the trip photographer, he’d been relegated to a leaky aluminum boat aided by two locals—one to man the outboard and the other to bail water with coconut shells.

During their time at Sherbro the group took up residence on a large commercial ship, a “tramp steamer” according to O’Keefe, named the Adelaide. Anchored in the lee of the island, the captain of the ship had a front-row seat to the spectacle of massive silver fish rolling in the tea-colored waters of the channel; after losing several Rapalas to them he had alerted some angling friends, which eventually resulted in Affre, Pate and the others arriving to see what could be done about pulling a world record from the bunch.

After a couple of days, the photo opportunities seemed to have been exhausted. “You can only take so many pictures of the jungle,” O’Keefe says. Though he did explore the nearby shoreline and some of the villages on the island, a sandstorm killed the light, as it were, heaping on more impediments to photo-making.

“I really wanted to catch some fish,” O’Keefe says:

But, I did not [flyfish] for the first two or three days because I was going to give Billy “right of first refusal,” you know, and he gave me a Billy Pate reel, he mailed it to me before the trip; it was engraved with my name on it. And even though he gave me this 12-weight reel, I still didn’t put it to use until the second half of the trip, which might have only been a couple of days. So those first few days, I fished with a mooching rod. We didn’t really have guides, just the local villagers who knew where the tarpon were, and I don’t even remember whether I had a piece of fish meat on my hook or a lure, but I wanted to flyfish so bad. Then when I saw [Pate] fishing Florida-style I thought, “God, now we’re both wasting our time.” And so, probably the third or fourth day, I rigged up.

“Then when I saw Pate fishing Florida-style I thought,

‘God, now we’re both wasting our time.’”

above Brian O’Keefe fights a large tarpon in the Sherbro estuary. “Billy, Brian and I were the only ones flyfishing. All other anglers that week (French and American) were fishing conventional tackle with live mullet or dead baits.” Photo: Pierre Affre

Though uncertain about how much fishing he’d actually get to do, O’Keefe had done his homework. He knew that West Africa was known for big fish—not only tarpon, but also barracuda and jacks, jacks that would turn out to be so aggressive they’d take a hookless lure and he’d still land them on the beach because they simply would not let go. He knew from talking with Tom Gibson and others that the typical Florida-style tricks might not be the primary way of catching the tarpon. His kit included floating lines and crab flies, but he also brought heavy sinking lines and sailfish flies—8-to-9-inch concoctions—on a tip that the tarpon at Sherbro were feeding on baitfish deep in the channel. This was river-mouth fishing of the sort he’d seen and done in Costa Rica.

The group fell into a typical fishing lodge routine, minus the lodge. After breakfast each morning, they’d check the tides and head out to the fishing grounds—Pate, Gibson and others in the pair of Whalers, O’Keefe in the leaky jon. They heard the occasional machine gun chatter in the hills around the island—likely just being fired into the air. On April 8, a conventional tackle guy named Ged Fleming hooked and landed a fish that, once weighed, tipped the scales at 242 pounds—a new record, and one that broke the record Fleming had set just a few days before. Through a translator, the captain of the Adelaide asked one of the locals, “If this is 242, then how big do the tarpon get here?” The villagers discussed the matter among themselves and replied: 300 pounds. The current world record is 286.

In reality, there’s no doubt O’Keefe (and Pate and Affre) hooked fish on the fly even larger than the one that would end up in the record books that week. With that fish, O’Keefe says, he got lucky.

You could tell they were massive fish, and most of them came to the top and jumped, just like all tarpon do; this [record] fish did a combination of runs and spectacular jumps, and because of the runs and jumps it tired out. If it had… just stayed deep and hunkered in the tide in the current, they’re almost unlandable; so, my fish was airborne and running and really working me over, but, in the long run, I didn’t get worked over because I had it in and landed in 20 minutes. Normally, a fish that size, if it just laid low and used its constant pressure trick—it would have been hours. So I was kind of lucky that I hooked a jumper.

I got it up to the boat and the guys grabbed it by the mouth and the gills; it had its tail sticking up on one side and head on the other.

LEFT TO RIGHT “When I told Brian he should weigh his fish after gaffing it (on the certified scale brought by Tom Gibson) Billy read the weight: 187 pounds 6 ounces. It was a new record for the 20-pound tippet class, though Billy still held the world record of 188 pounds on 16-pound tippet.” Photo: Pierre Affre

“Billy Pate casts to about a dozen fish we clearly saw feeding and rolling under the birds in the tea-colored water of the estuary. That year, tarpon fed on the surface during tide turns for a good hour every day, apparently on small shrimp. When I returned with Billy Pate and others in following years, we never again saw the feeding frenzies of April ‘92.” Photo: Pierre Affre

At times, he had a hookup on nearly every cast. And in every other case he lost them. They broke off. They jumped and threw the hook. They hunkered, deep and unmoving, in the way only decades-old, 200-pound fish can.

O’Keefe hadn’t necessarily wanted to fish the IGFA leader, but some members of the group—with a thought toward creating a destination fishery—suggested he stick with a leader that could put Sherbro in the flyfishing record books. He obliged. O’Keefe’s frustration with the IGFA leader had less to do with the breaking strength of the class tippet and more to do with the length of the shock tippet. In his calculation, the maw of a plus-200-pound tarpon was wide enough to make the shock tippet moot even if it were wire. If a fish were hooked on the left side of the mouth and going away with the leader crossing through the right side of the mouth, the class tippet would inevitably rub through on the tarpon’s rough-hewn jaw.

“I’ve always disliked world records,” O’Keefe says, “and think that people that chase world records—and that’s why they fish—are just, I don’t know…” Here he hesitates. He’s likely talking about some of his friends. Or at least friends of friends. O’Keefe’s been around this industry for the better part of five decades. You’d be hard-pressed to find him even lifting native fish from the water these days. He’s an ambassador for Keep Fish Wet.

He goes on, “I don’t want to call them all jerks but they’re…they’re demented.” One hears the bemused smile on his face as he says this.

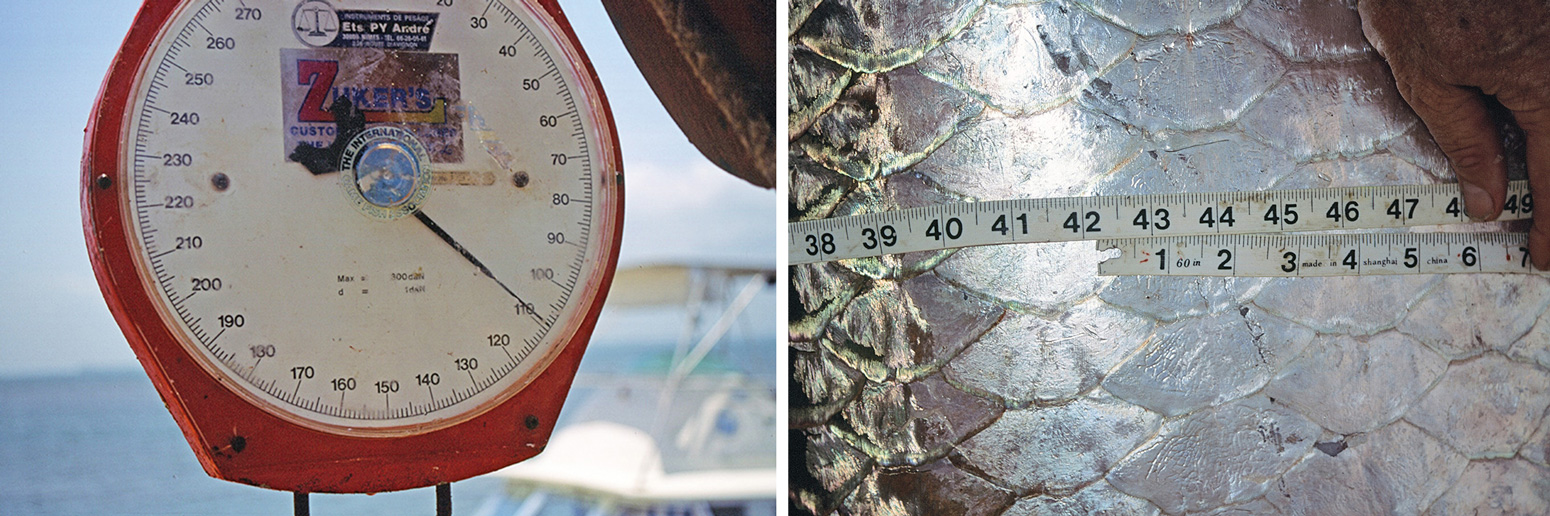

LEFT TO RIGHT “One-hundred nine kilograms, or 240.30 pounds. Tom Gibson’s certified scale weighed our five tarpon for science and the record books. The fish were so large that we had to dig a hole in the sand, under the scale, so they would not touch the ground.”Photo: Brian O’Keefe

Forty-two inches: tarpon with this girth and a corresponding average length would be estimated to weigh 210 pounds. Photo: Brian O’Keefe

O’Keefe hooked 18 tarpon and landed one of them on that trip during, at most, two days of flyfishing. According to Pierre Affre, in his trips with Pate and others to Sherbro over the years—before the civil war spilled over into their little tarpon Shangri-La in the mid-’90s—they continued to hook massive tarpon on the fly and continued to get absolutely destroyed by them. Pate himself never took a world-record tarpon in West Africa.

The disparity in records—a majority of conventional tackle records in West Africa on the one hand, and nearly all flyfishing records set in Florida on the other—is comical in a way. One could say it’s a matter of tactics, or ethics, or some combination of the two, but it also sheds light on the limits of those tactics or ethics. Pate wanted to hunt the fish, sight-casting to individual tarpon visible in shallow water or at least near the top of the water column—a noble pursuit, perhaps, but at the end of the day just one among many possible techniques. The problem is, where Sherbro was concerned, this wasn’t the way to do things. The channel is deep, influenced by heavy tidal currents, and at certain times opaque from the river’s muddy discharge—a far cry from Homosassa or Islamorada.

At the end of the day, it would seem, flyfishing for tarpon records at Sherbro under the IGFA rules was something of fool’s errand. Affre more or less said as much when asked why another record had never been caught there, despite the numerous records taken on conventional gear. “The fish,” he said, “were just too big.”

ABOVE “In 1992, we were using the same types of flies we’d fished from 1978 to 1981 in Homosassa, FL. In later years at Sherbro, we tied bigger flies, sometimes on large circle hooks.” Photo: Pierre Affre

It may be to the credit of fly anglers that even in as inane a pastime as record-chasing, a certain degree of decorum holds. Aside from the shrinking ranks of record-chasers during the last decade or two, and the obvious difficulty of hooking and landing a 200-pound fish on fly gear in deep water affected by tidal and river currents, the fact of the matter is that most fly anglers in pursuit of the hallowed “silver king” have a set way of doing things.

In any case, the irony runs deep. Pate lobbied the IGFA to create the 20-pound Tippet Class for tarpon, because, as Billy Knowles says in Lords of the Fly, “‘[Pate] was always trying to change the rules so he could catch more records.’” Soon after the 20-pound class became official, Tom Evans set the bar at 180 pounds in 1991—possibly more to annoy Pate than anything else, given his dislike of the man.

Of course, as if to prove a point, Sherbro Island didn’t give up any records to Pate or Affre or any of the other fly anglers who’d put any amount of time into the pursuit of world records. Sherbro Island gave up a record to O’Keefe, a former guide, ski bum, photographer and sales rep from the decidedly tarpon-less Pacific Northwest for whom records were pointless. He just wanted to shoot some pictures and catch some fish. The particular set of numbers associated with the fish were less important than the fact of the fish itself—where it came from, how, who was with him when he caught it. O’Keefe cast his sinking line and massive flies into the current at Sherbro Strait, mended like he was trying to drop an intruder to a winter steelhead on a cold Northwest river, and stuck a 187-pound tarpon on the tippet class Pate had fought so hard to establish.

They hunkered, deep and unmoving, in the way only decades-old,

200-pound fish can.

LEFT TO RIGHT Daniel Lopuszanski, who partnered with Michel Delaunay and Patrick Bermane to build a fishing camp at the mouth of the Sherbro River in 1993, shows off some worn-out circle hooks. Photo: Pierre Affre

Brian O’Keefe strikes a pose with his local guides as they lift his record-setting tarpon into their jon boat. Photo: Pierre Affre

The fish’s end was almost ignominious. After the fight, they hauled the man-sized tarpon onto the tiny boat that already held three men and motored to a sandy stretch of beach where a makeshift weighing station had been constructed: rough-hewn boards nailed to a pair of logs, pipes caving under the weight of the fish. The fish was so long they were forced to dig a hole in the sand below it to allow it to swing free on the scale. It topped out just 10 ounces lighter than Pate’s (at the time) flyfishing world record of 188 pounds. A coffee cup weighs 10 ounces, without the coffee. Still, according to those who knew him, Pate seethed.

Someone took pictures. Someone else hacked through the tarpon’s head to extract the otolith so that it might be studied by a scientist in Florida. The fish’s flesh was portioned further and shared with the local villagers. For better or worse, that was the end of the fifth-largest fly-caught tarpon ever recorded by the IGFA.

When he returned to Oregon, O’Keefe mailed the leader to the IGFA headquarters in Florida to be tested. (If he still has the fly, he doesn’t know where it is.)

A few weeks later, on April 29, 1992, a group of young, frustrated military officers led by a fresh-faced captain in the Sierra Leone army named Valentine Strasser launched a coup in Freetown, sending President Momoh into exile. Sierra Leone crept further along the path to civil war. Somewhere near Sherbro a tarpon rolled, and a soldier shot a machine gun into the sky.

The fish was so long they were forced to dig a hole in the sand below it to allow it to swing free on the scale.

ABOVE “Billy Pate fought this huge tarpon, estimated to be over 300 pounds. The fish headed for the ocean where we lost him aboard a 15- or 16-foot boat in fairly dangerous swell.” Photo: Pierre Affre