Profile

Sangha

The Rivers and Rhythms of Jason McGerr

This isn’t the first time we’ve done this drive. McGerr is a regular flyfishing pal and my neighbor. For the past 20 years we’ve pounded out separate livelihoods in Seattle’s urban hustle and growth, but tonight we’re headed back to mountainside homes nestled in a north-facing forest on the outskirts of nearby Bellingham.

From our doorsteps, we can look out over the crooked horizon of the Cascade Range with its foothills shrouded in nightshade and shadow. Hidden inside their silhouettes is a beginning, or origin, born inside valleys with snow melt and rain headwatering over cobbles and sand. Down below, these valleys braid together and become the confluence of every river McGerr has ever stood in, and tomorrow morning we’ll be swinging flies through its slipstream.

This is home.

above Jason McGerr pauses on the North Fork of the Nooksack River near Bellingham, WA. Photo: Ryan Russell

As the cityscape of Seattle disappears in the rearview and the high-rise lights fade, our eyes adjust to the distant dim and glimmering stars mirrored on the dark coastal rivers we traverse during the drive; Snohomish, Skykomish, Stillaguamish, the Skagit—big rivers McGerr has known and loved and fished since he was a kid.

He’s lived nearly his whole life in Bellingham. Music takes him downstream, out to sea and around the world where he feeds and grows, but Bellingham is where he was born, where his family lives, and where he and his wife are raising their two boys. And for most of his life he’s bedded down within a couple miles of Whatcom Creek, an embryonic body of water moving through town, and his life, like an arterial.

His house posts high above Lake Whatcom, a clean body of water pooled below still-pristine Cascade mountains. In the backyard are 10,000 wild acres of woods. From his living room, McGerr can glimpse the lake where it spills off and becomes the headwaters of Whatcom Creek. The brief, 3-mile stream is largely bordered on both sides by native forest and pours into Puget Sound.

“I always wanted a house on this hillside with the woods at my back,” he muses, adding, “I live a mile from the creek I fished for the first 18 years of my life.”

It’s more than a house though. His home is a perch from which he can see the topography of his whole life like a hawk on the wing, a self soaked in river water and rhythm.

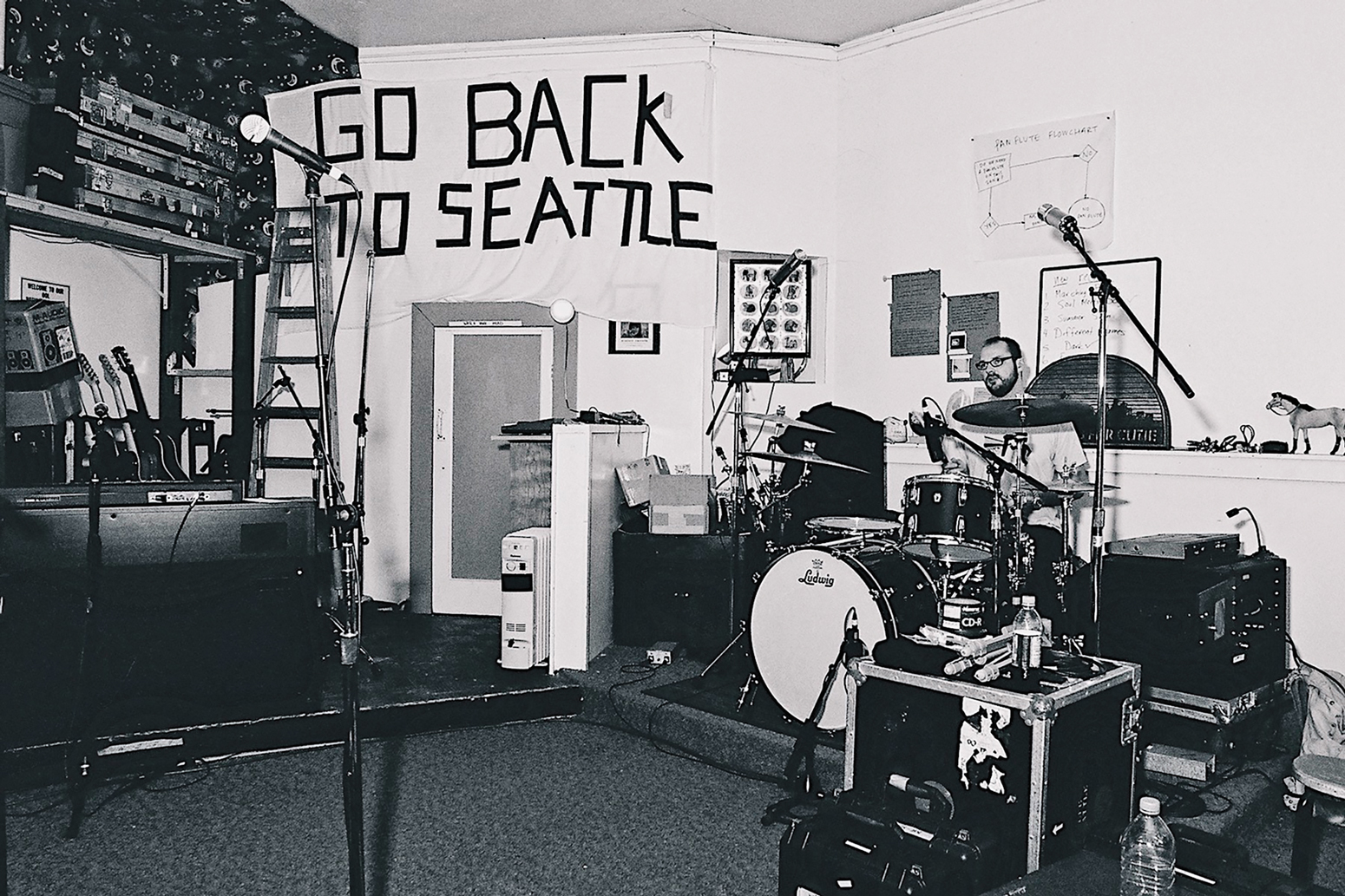

above

Jason McGerr sits behind his drum kit at guitarist and producer Chris Walla’s Hall of Justice recording studio in Seattle’s Fremont neighborhood. Photo: Ryan Russell

Death Cab for Cutie has achieved a remarkable level of success during the past 20 years. They’ve collaborated and toured with everyone from Neil Young to Pearl Jam to Chance the Rapper, and routinely sell out iconic venues such as Colorado’s Red Rocks, Madison Square Garden, the Greek Theatre and the Hollywood Bowl. Their catalogue includes nine studio albums, five EPs, two live records and two DVDs; they’ve had gold and platinum record sales and received nine Grammy nominations along the way. What began as a group of friends in Bellingham playing basements and house shows has grown to worldwide acclaim and helped define the indierock genre, and after 1,500 live shows together they show no signs of slowing down.

However, before he rocked the world over, McGerr was a quiet kid who grew up knee-deep on freestones with a fly rod in his hand and a pair of drumsticks in his back pocket. As a child he fished Whatcom Creek regularly and during high school worked at the local fly shop—H&H Sporting Goods, just two blocks from its banks. He came of age in the creek, pulling patterns from the current and finding rhythms with a cast, and learned to listen to the rudiments beneath the music of it all and catch the song.

An hour into our drive home, as we enter the dark and vacant upriver expanse of the Skagit Valley, I ask McGerr which is greater: the journey out or the journey back? He replies, without hesitating, “I think the air that first enters your lungs will always breathe life into you. …Every time I go home, no matter where I’ve been in the world, no matter how beautiful or incredible the places or experiences were, I park behind our house, step outside and breathe in this air—literally, the first air I inhaled—It gives me goosebumps.”

above From left to right: Ben Gibbard, Chris Walla, Jason McGerr and Nick Harmer of Death Cab for Cutie take a break from recording in April 2008 shortly before the release of Narrow Stairs. The band gathered at Hall of Justice to film a series of live performance sessions in advance of the album’s release.Photo: Ryan Russell

At just 6 years old, McGerr won the annual Whatcom Falls Fishing Derby—a popular opening-day event that takes place in a slow-water section of the creek known as the derby pond. His uncle gave him his first fishing rod, a green-and-white Zebco push-button cast, and he was the first to limit in that year’s competition, earning a gift certificate to the same fly shop he’d later work at. He fished Whatcom Creek nearly every day that summer and each of the summers thereafter, wandering farther along its banks with each passing year.

When he turned 10 he acquired his first fly rod, a four-piece Fenwick.

“I’ll never forget the black velvet rod sack,” he says. He used a shoelace to tie it up behind his back like a quiver. It was the mid-1980s, Bellingham was a small town, and he had the creek mostly to himself.

“I remember when Woburn Street [now a main thoroughfare with a bridge over Whatcom Creek] dead-ended at the creek,” he says. “Starting that summer my mom would drop me off there at 9 a.m. and not pick me up till 4. I’d fish the cliffs above Woburn, hoof it all the way up past the waterfalls and through the canyons. There was a small trail on the south side of the creek, and I knew all the slots and bends and pools. I spent hundreds and hundreds of days in that creek, fishing it all day long and mostly by myself.”

above “Through most of my youth, we’d join my cousins on their summer camping adventures. As much as I enjoyed all the group stimulation and campground bike laps, I started bringing a rod on those trips and eventually transitioned to more solitude practice and subsurface searching.” August 1982. Photo: Courtesy Jason McGerr Family Archives

In the canyon was a hideaway, a small cave where he stashed fishing supplies inside a coffee can. For lunch he’d sneak produce from a nearby garden and cook fresh-caught trout over a campfire. It was “Red Dawn-style,” he laughs, saying he also carried a survival knife, the handle capped with a compass ball and stuffed full of leader and flies.

It was a summer of boyhood wonder, wading with untethered adventure and freedom and catching sea-run fish on a fly. It was also the summer he began hitting the drums, taking lessons hoping to play in the middle school band. But that same summer he fell in love with fly rods and drums was when his parents divorced and his dad left, going vagabond around the country. The only upside came when he and his mom moved into a duplex closer to Whatcom Creek, now just a bike ride away.

Crossing the Skagit River bridge, above the deep, still water the of river’s mouth, I ask McGerr what he thinks happened between his parents back then, and why. He says he remembers walking into the kitchen, surprising his parents seated at a small table, “my mom on the left, my dad on the right,” and interrupting a conversation that their marriage was over, and that was it.

“When I realized my dad left our house, I’ll never forget the night, it was like when a song ends and there’s dead space, dead air, and you have to sit with what you’ve listened to and sort of think about it, waiting for what comes next,” McGerr says. “But that period for me, sitting and thinking, wasn’t the several seconds between songs. It was a seven-year wait between songs before I saw my dad return to Bellingham. It was a time that I blocked a lot out, and I knew, I need to just fish—I need to spend a lot of time by myself and just go out into the woods for as long as I can and fish.”

I wonder, in response, if he recognized at the time some form of release was being acknowledged in the creek, and his answer needed no reply.

“Standing in water,” he says, “bathing yourself and your thoughts, bathing your life in general, and casting in search of something you can’t see… that’s exactly what it was. And the only way to find it is to sweep the dark bottoms, swing through it. Circumnavigate the shoreline. And wait. All those searching patterns. They were just a metaphor of my life. They still are.”

During middle and high school McGerr regularly skipped class to fish the creek and nearby mountain lakes, forging notes from his mom to excuse the absences on days he felt the need to disappear, “because today doesn’t feel like a school day to me,” he recalls thinking, “today feels like a day to go to the creek and fish.” On other days he’d lose himself behind his drum set, practicing for three or four hours at a time. Yet even on the days he skipped school, he’d return for band practice in the school’s jazz, concert and marching bands.

above “At the northwest corner of Lake Whatcom—the start of Whatcom Creek—Bloedel Donovan Park had a snack bar where I could buy all the junk I needed to keep myself stimulated. I’d sunburn my back, facedown with goggles—or without—searching for minnows and crawdads. Sometimes I’d even spot a cruising smallmouth bass, but trout were far more elusive, which kept me searching.” Photo: Courtesy Jason McGerr Family Archives

As he grew, McGerr’s dual passion for moving water and music began to mature and even started to earn him a paycheck. From the ages of 14 to 18, he worked after school and on weekends at H&H, fishing obsessively and following leads that came in from the prolific steelheaders frequenting the store. He was also picking up paying gigs with local bands; standing 6 feet 2 inches tall by age 16, and unshaven, he could fool club management into letting him play inside bars.

“As I got a little older,” he says, “those two things, flyfishing and drumming, really came into focus and both were vying for my attention and time, and the only reason I didn’t become a flyfishing guide—something I really thought about—was because a future in music began to feel attainable.”

After high school, McGerr moved to Seattle. He worked in music shops, played in a couple of small bands and even made some records. It was the early 1990s and the whole world was dialed in to the city’s frequency and its booming alternative music scene. He also became a popular instructor at the famous Seattle Drum School, teaching upward of 60 students a week. The industry started to regard him as a sought-after educator, and drummers from all over began reaching out to him for advice, lessons and direction.

John Wicks of Fitz and The Tantrums (who has also recorded with Bruno Mars and CeeLo Green) was at the drum school back then, and the two remain close friends. “He’s a true craftsman,” Wicks says of McGerr, “and my respect and admiration for him continues to grow. He’s so skillful, patient and humble.”

It wasn’t until he was 28, in 2002, that McGerr joined Death Cab for Cutie. A year later they released their breakout album, Transatlanticism, and things began to skyrocket.

“We were on tour from the release of Transatlanticism through the release of our next album, Plans, on the road continuously from 2003 till the end of 2007,” McGerr says.

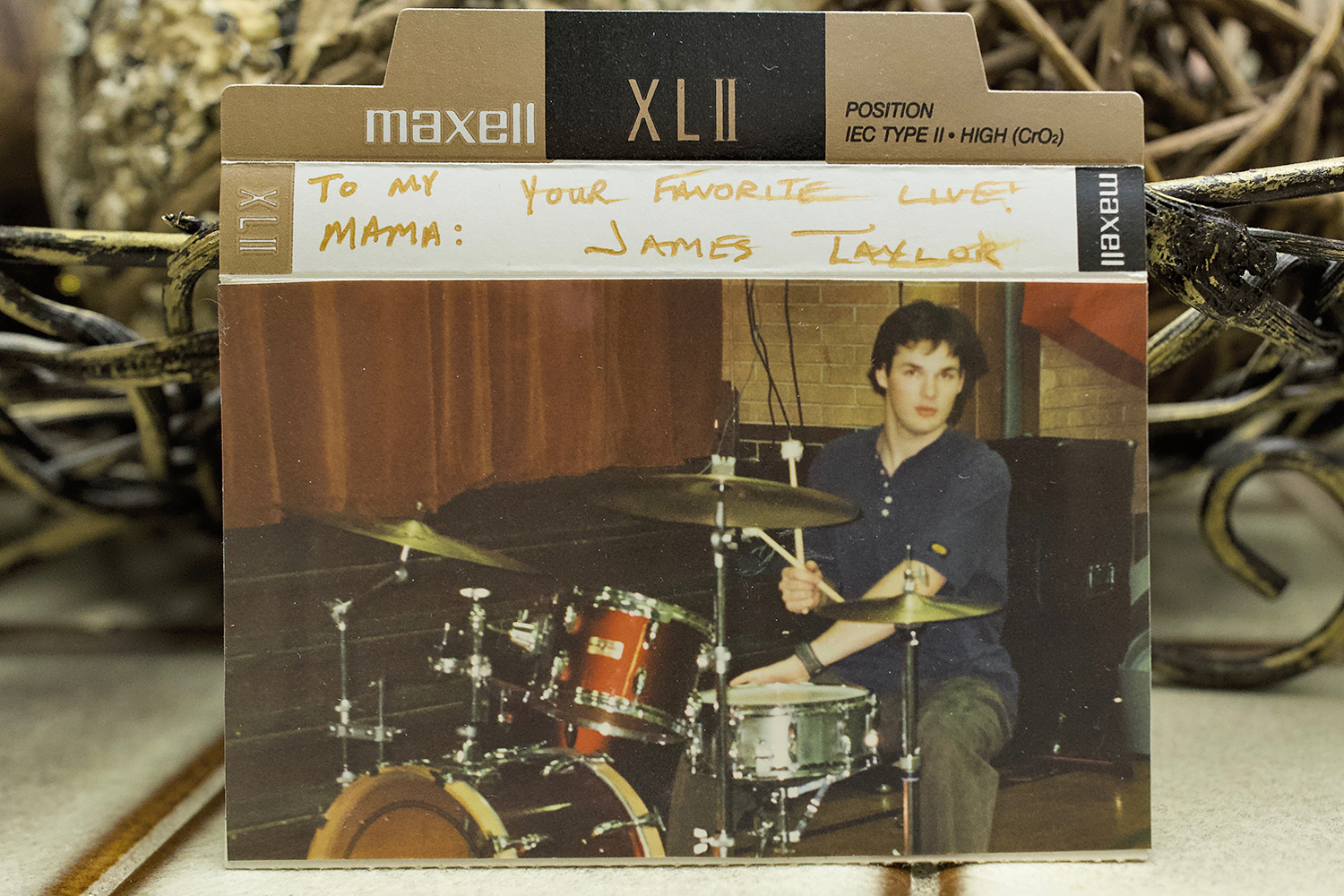

above “My mom has always been a lover of music. It was on in the house, the car radio, the classroom she taught in for years, everywhere. Occasionally I’d make mix tapes of her favorite songs and artists, complete with my own album artwork. Sometimes on weekends she’d work in her classroom while I would run wild in the empty halls of Parkview Elementary. Eventually I got the green light to set up my drums in the gym, which enabled me to recreate the sound of John Bonham in a coliseum. This cassette pic was taken around my senior year in high school while giving my very first ‘Drum Set Clinic’ to my mom’s second-grade class in that very same gym.” Photo: Jason McGerr Family Archives

Death Cab became a household name, and their songs started popping up in television shows and movies like Grey’s Anatomy, Six Feet Under and The O.C. They were the musical guests on Saturday Night Live and made multiple appearances on all the network late-shows. In 2009, the blockbuster book-turned-movie, Twilight, featured their single, “Meet Me on the Equinox,” during the film’s closing credits; the movie soundtrack went platinum.

Throughout the band’s rise, McGerr found opportunities to wet a line during days off between shows. Sometimes that meant guided floats in Europe or deep-sea charters off the coast of Australia; more often it meant pulling smallmouth from no-name bass ponds behind hotels in the middle of America, just to kill time.

His friend, Sean Carey, drummer and multi-instrumentalist for Bon Iver—and another lifelong flyfisher—does the same. Like McGerr, Carey still lives in his small Wisconsin hometown, wading the same streams he’s walked his whole life. Carey said he’s been listening to McGerr’s drumming “ever since Transatlanticism rocked my world as a freshman in college in 2003. His drumming is so detail-oriented, technical but with great ease of motion. Grounded. Selfless and confident. I need to fish with him as soon as possible.”

These are the bedrock qualities of McGerr: He’s grounded and giving, he looks for opportunities everywhere and finds them, and has a work ethic that’s tireless, generous and intentional. When he’s home, the soft lights of his studio flicker on around 5 a.m. and he begins each day with a practice pad and a few hours of study before his family wakes. He leans heavily into personal growth and reads voraciously, and still practices drums with discipline for hours every day. Simply put, he views himself as a student. “My whole life,” he says, “I’ve put a ton of emphasis on continuing education, to reach out to people who are the best and to learn from them.”

above On June 8, 2019, Death Cab for Cutie [DCFC] headlined the Nelsonville Music Festival in Nelsonville, OH. Festival artist backstage compounds, as they’re affectionately referred to, are always unique to the festival. In this case, the promoter provided fishing rods so artists and crew could try their luck in the pond behind the stage. McGerr landed a few smallmouth while DCFC guitarist Dave Depper strummed away. Photo: Rob Whited

This doesn’t stop when he’s on tour. Recently, in Glasgow, Scotland, he spent a day off between shows taking a spey casting lesson from world champion fly caster Andrew Toft. The next day he sat for a lesson with 10-time world champion bagpipe band drummer Steven McWhirter.

Even when McGerr isn’t standing in a river, he always seems to be fishing. Whether that’s casting in his front yard, or drifting rhythms over his drums, he’s looking under the surface for an understanding not readily apparent. This translates into the company he keeps as well.

As often as possible McGerr and I pilgrimage to Missoula, MT, to visit friends—they are authors and musicians, and some dangerously good flyfishermen. They’re fraternal spirits as well, friends held tightly in the river’s grip, brought together by its wonder-filled ways. Our occasionally long sessions under the Big Sky highlight a shared purpose that shoots farther than our fly lines and reminds me of a Sangha—a word found in the oldest known Buddhist texts. Translated from Sanskrit, it means a community or order that encourages you and helps you grow; it’s a crew that takes you farther than you could otherwise travel alone. It’s a band.

One such friend, Chris Dombrowski, is on point when he cautions, “There’s nothing like a little Zen-talk around the campfire to get you a boot in the ass,” but adds, “nonetheless, a sangha has the potential force of a river, the many moving as one.”

Having guided full-time for more than 20 years, Dombrowski is one of the most established fly guides in western Montana. He is also an acclaimed writer and poet, and I’ve long understood he inputs wavelengths not ordinarily perceived, his sense frequencies ranging far.

“The first time I saw McGerr in a solo, from backstage,” Dombrowski says, “I knew the trout have no chance at all. His hand-eye coordination is absurd.”

To be in the company of friends like this is to be in an honest place, a place where you can’t hide. It’s a place too real for charades, and this makes you better.

Another friend, novelist David James Duncan, watched McGerr cast a country mile, and remarked, “Casting long is like stretching before you go for a run. Once Jason starts fishing, he makes short, accurate casts and lengthens them gradually till he’s covered all the good water.”

On a handful of occasions Death Cab for Cutie has played a concert in Missoula. During the day we wade and float the wild rivers of western Montana, and in the evening we gather with the band’s audience and watch McGerr looping sounds in a rhythm all his own and bringing songs to the surface. Once, in the middle of the song “We Looked Like Giants,” he erupted into a free-form drum solo with all four limbs hitting feverishly and in time signatures independent from one another. He sang, too, full-throated and guttural. He began to rise, playing standing up, and amid a swirl of sound the crowd rose with him and erupted in a cheer, and I wondered in the moment if anyone’s feet were still on the ground, including his.

It was a day spent drifting rivers and walking water, and it ended with reverb and sustain that left everyone feeling weightless. McGerr’s old friend, Wicks, says it best: He wishes everyone would “take a page out of the McGerr playbook of Life. The world would be a calmer, happier and more musical place.”

above Jason McGerr searches on the North Fork of the Nooksack River near Bellingham, WA. Photo: Ryan Russell

Approaching Bellingham, McGerr asks if I remember wading an upper section of a not-to-be-named creek the day after that particular show. Of course I do; the day was surreal and I tell him my view of life’s potential explodes when we’re all there. He says this is happening because of a disconnect from the rest of the world, that our being there is a big, long meditation, “for however long we’re there, we detach.”

He’s right, we detach and almost everything slips away. All but the nonmaterial slides downstream, rinsed off by the river. The transient and the impermanent tumble toward the sea and leave behind things beyond the grasp of gravity, the not-things that hover. The river is still there with a pulse in its current and the rocks roll under it with a pulse all their own. In the runs and riffles are the rhythms and revelations and answers rising in reply to a prayer. And still there, over your shoulder, are your friends, and floating around them are their songs.

This is the sangha.

“Every time we go to Montana,” McGerr says, “and I’m hanging with world-class writers, a world-class guide—world-class friends, you know, deep spiritual people, that environment is like going to church. It’s a marriage of all these things that have been important in my life. And it also resonates, it reminds me of my past. It’s an adult version of what I was trying to do as an 11-year-old kid, to escape to a creek and let the world disappear for a while.”

It’s almost 2 a.m. when we arrive home, winding past the city limits and beyond the reach of streetlights. There is no moon tonight and the stars shine brightly, illuminating the darkness with halos and half-shades of navy. McGerr stops the truck beneath a grove of second-growth cedar behind his house. Before getting out, he says, “I’m fascinated by doing deep dives on all things. It may be why I’m back in Bellingham. You know how they say true mastery is… it comes from mastering the basics and launching off from there, mastering the foundation. For me, these are my basics, this existence, in this environment. I have all I need here, all the things I had in the beginning.”

above On December 8, 2018, DCFC performed at The SAP Center in San Jose, CA, for ALT 105.3’s “Not So Silent Night” holiday radio show. Here, McGerr inspects the layout prior to soundcheck. Photo: Rob Whited

Whether it’s sitting alone with an instrument or standing in a river or spending time with another human being bringing things into focus, McGerr has discovered the benefits of “deep practice” as he calls it. “It’s all part of the building blocks of admitting who I am, of having time away with just my own thoughts and endeavors.”

As I open the truck door for a brief trail walk back to my house, I thank Jason for the evening’s concert and mention it’s always a joy to watch him play. As an afterthought, I ask, “What do you think you’re going to do when the band is over, when the last song ends?”

“I’m just going to fish more,” he says. “Really. I really am.”

I have half a mind to ask him what time he wants to get on the water in the morning, but decide to keep quiet because it’s late and I know he’s exhausted. He’s been gone from home for the better part of the past year and a half touring in support of the band’s latest album, Thank You for Today. But as I turn off his driveway, he bellows down a “goodnight” and says he’ll swing by my place in a few hours. Still smiling, but not looking back, I wave over my head before ducking through a corridor of evergreens toward home.

At daybreak there is frost on the cutbanks with ice in the slow current and pocket water. I fish from stepping stones and feel warm, hearing the river and seeing the rhythms of McGerr. The river flows between mountains that touch the sky and makes patterns and braids from snowmelt and rain. It sings songs over the clattering cobbles and sand as the sunrise pushes aside the shade and glimmers. The light lays open and cradles an upstream field of late-winter wildflowers, a wellspring hidden under cerulean petals of forget-me-nots.