Profile

Searching for Sheridan

THE MAN AND THE MYTHS BEHIND The Curtis Creek Manifesto

My first copy of The Curtis Creek Manifesto was given to me by an old professor. He wasn’t much of a fisherman, but he knew about such things. I told him I’d taken up flyfishing, and he went looking for something in his shop. He stopped rummaging long enough to give a lecture on the mechanics of the pocket watch and the implications of its development on the oceangoing explorers of the Pacific Coast—namely Captain Cook, a distant relative of his. After the lesson, he remembered his task and produced a ragged pamphlet he called “The Book.”

That summer, when the professor drove home to Prairie City, OR, he invited me along.

We fished a creek in the Strawberry Mountains and the professor brought along an old bamboo rod with cracked ferrules and a too-small reel attached to the rod with duct tape.

His brother—a one-armed machinist who fished with an old Colt Navy on his hip—had stayed in Prairie City and wasn’t big on Portland fishermen. The old revolver, which didn’t fire, had once been a prop in the 1969 film, Paint Your Wagon. Lee Marvin, he said, had toted it around in front of the cameras.

By noon, the professor and his brother had killed two good browns for lunch and released a dozen more. I was shut out, but the two men were kind enough not to suggest they should have killed a third. “What’s the name of this creek?” I asked over a handful of sunflower seeds. They let the question hang before the professor replied, “Curtis Creek.”

“So,” his brother asked, “have you read The Book?”

“What’s the name of this creek?” I asked over a handful of sunflower seeds. They let the question hang before the professor replied, “Curtis Creek.”

“So,” his brother asked, “have you read The Book?”

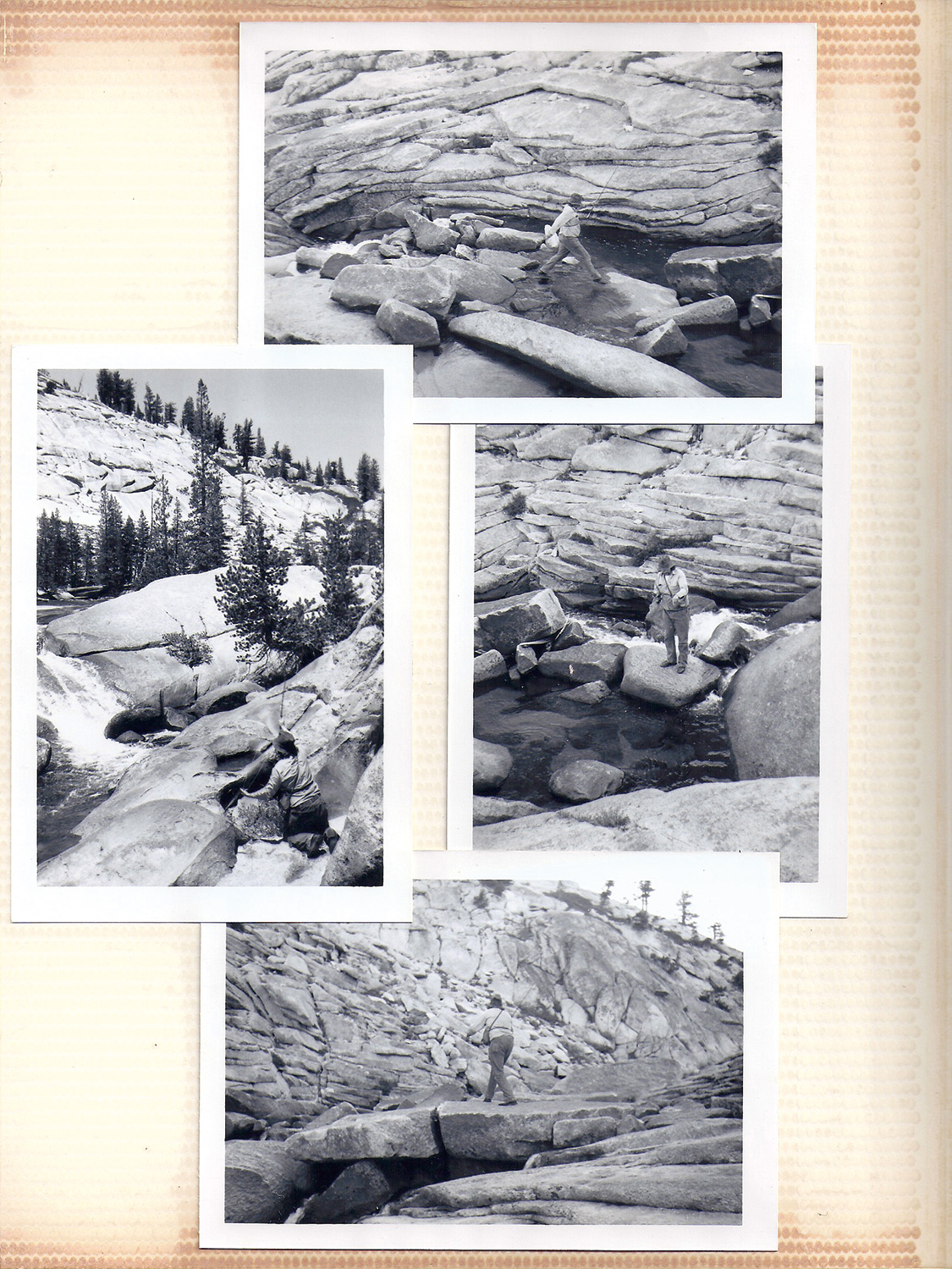

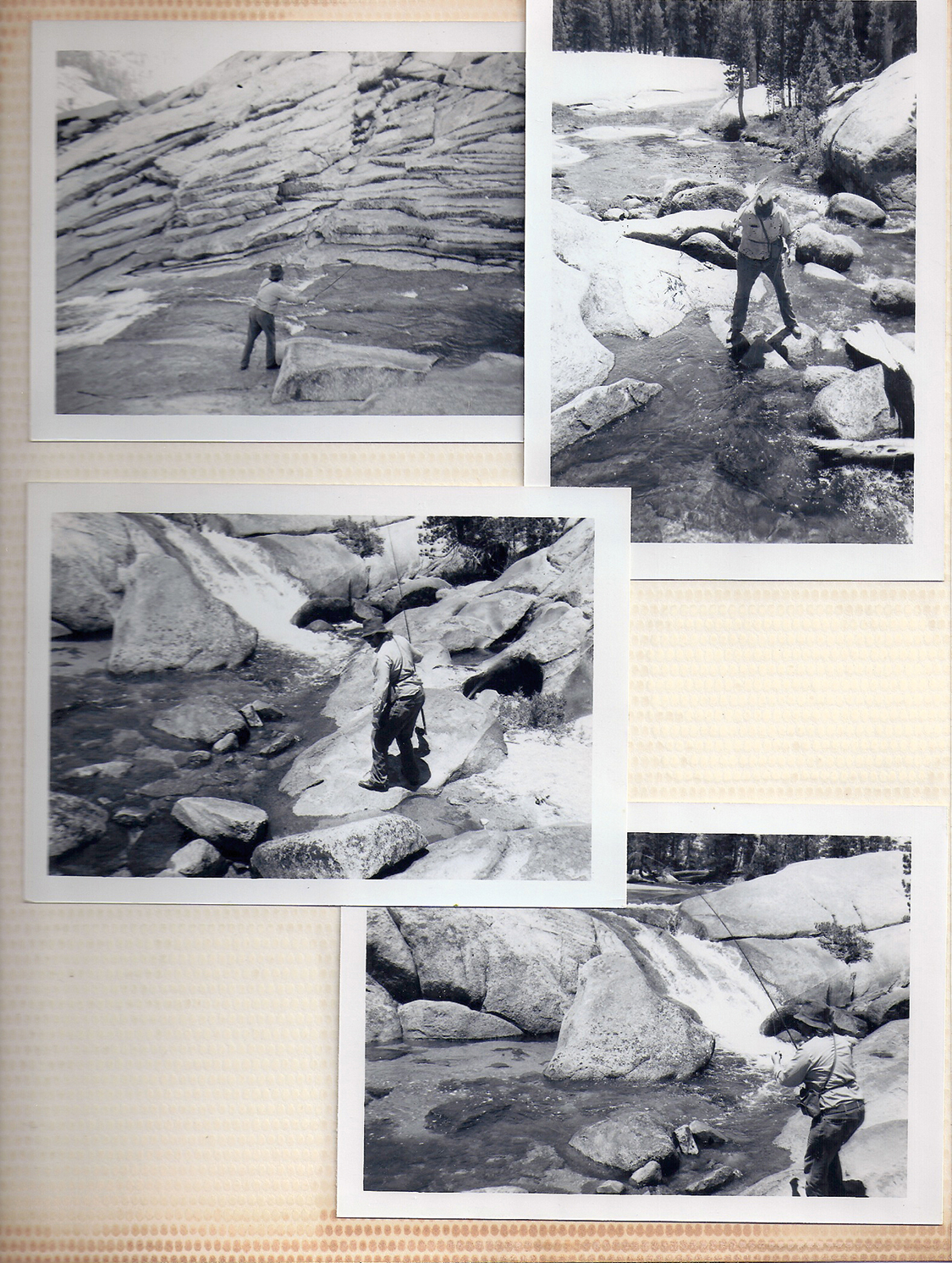

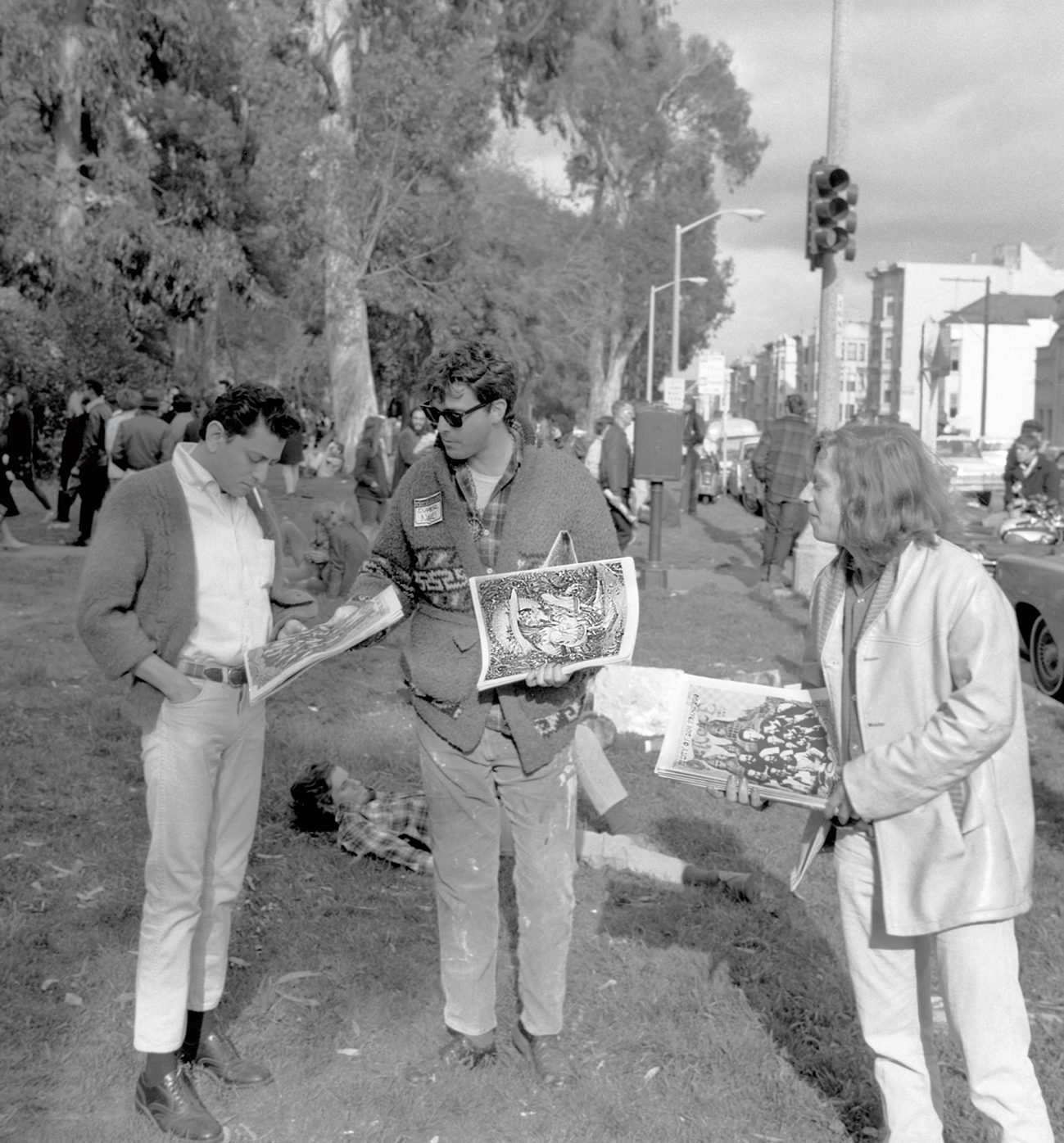

ABOVE “After my brother Sheridan died, I was sifting through his stuff and came across these photos and placed them in a photo album. Sheridan was always the flyfisherman, I wasn’t. Regretfully, I have no idea where or when the pictures were taken. Sheridan died March 31, 1984 and I still miss him very much.” Photo: Michael Anderson

“There were a lot of people dirtbagging then, but nobody fished except me and him. We’d fish the Merced and all the little creeks. There’s a series of deep pools below upper and lower Yosemite Falls. It was a pretty easy climb, so we’d fish them from a rappel. We caught some nice 14-inch rainbows that way that must have come over the falls.” —Yvon Chouinard

In the spring of 1975, an unsolicited manuscript landed in publisher Frank Amato’s mailbox in Portland, OR. It was a 48-page fishing instructional done entirely in comics. “I liked it immediately,” Amato said. “The humor, the straightforward presentation—I thought it was just brilliant.”

The envelope had a San Francisco return address and enclosed was a phone number for the author, Sheridan Anderson. “Normally I’d send a letter,” Amato said, “but I was so interested I called him and asked if I could come to San Francisco.”

It was the first time Amato had flown anywhere to meet a potential author, but before the week was up he was on a plane to San Francisco. “Sheridan cut quite the image,” he said. “He picked me up at the airport wearing a long black coat and a black, brimmed hat. He was a dead ringer for Long John Silver. He even walked with a limp.”

They discussed the book at Sheridan’s apartment in the Mission District, but Amato’s mind was already made up. He was in San Francisco to meet the man behind the manuscript. He flew home and mailed Sheridan a contract. In 1976, Amato published The Curtis Creek Manifesto. Immediately popular, the book reimagined the instructional flyfishing guide. Illustrated in Sheridan’s irreverent underground comic style, the book was an engaging, hilarious and completely refreshing take on a centuries-old sport. It was a breath of fresh air and it invigorated a generation of anglers 16 years before A River Runs Through It hit the big screen.

“The book sold like crazy right out of the gate,” Amato said. By the 1980s it was being translated into German and Japanese and, according to Amato, it sold especially well in Japan. Since 1976, it has been reprinted at least 20 times and sold several hundred thousand copies.

“The book is pure Sheridan,” Amato said. “Nothing changed in the layout, the writing is 99 percent unedited, it’s all hand done—he was a real master.”

“I heard later that he had done some off-color rock-climbing cartoons,” Amato said, but before The Manifesto, Amato, like most fishermen, had never heard of Anderson. It was Sheridan’s first fishing work and, in spite of its resonance, it would be his only one. But by the time The Curtis Creek Manifesto was published, Sheridan had been contributing to the climbing magazine Summit for more than a decade. He also illustrated a pair of how-to books on the subject, written by the late Royal Robbins and, throughout the ’60s and ’70s, his cartoons appeared regularly in Ascent, Mountain, Mountain Gazette and, under the pseudonym E. Lovejoy Wolfinger III, in the “off-color” climbing ’zine, Vulgarian Digest.

“The book sold like crazy right out of the gate,” Amato said. By the ’80s it was being translated into German and Japanese and, according to Amato, it sold especially well in Japan. Since 1976, it has been reprinted at least 20 times and sold several hundred thousand copies.

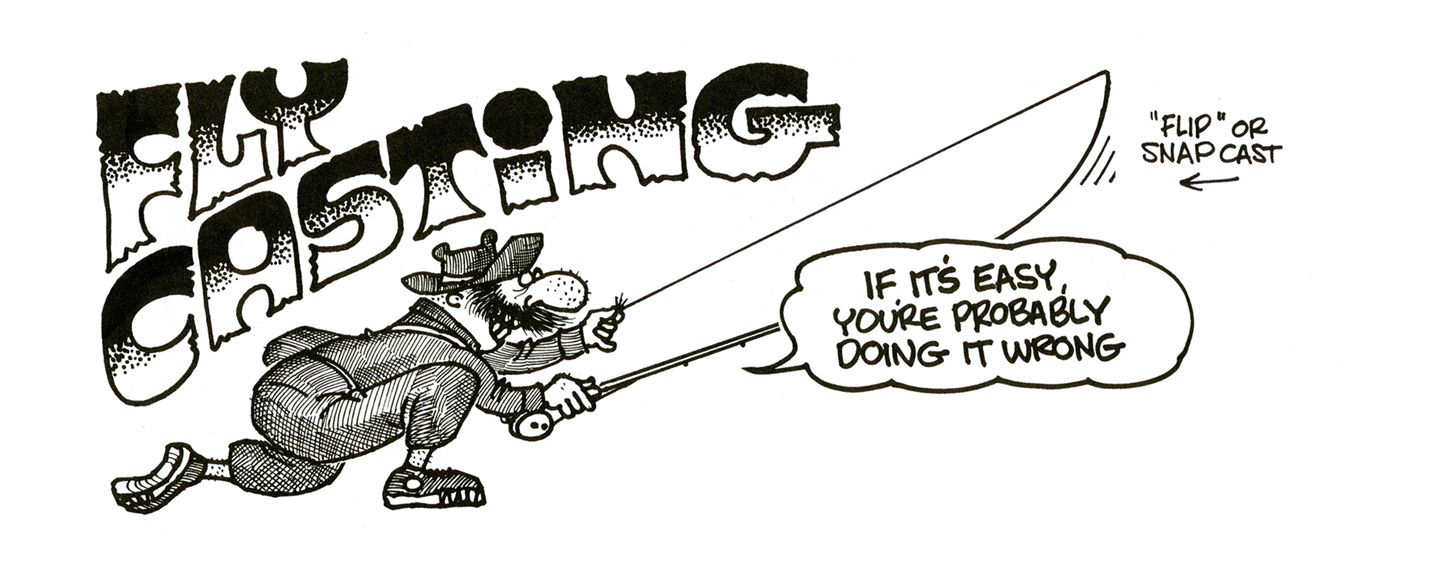

ABOVE Anderson dubbed this the illustration the “’Flip’ or Snap cast.” Today we’re more likely to call it the bow-and-arrow cast. Regardless, his caption, “If it’s easy you’re probably doing it wrong,” is as true today as it was when The Curtis Creek Manifesto was published in 1978.

Illustration: The Curtis Creek Manifesto, Sheridan Anderson, Copyright 1978, Frank Amato Publications, Portland, OR

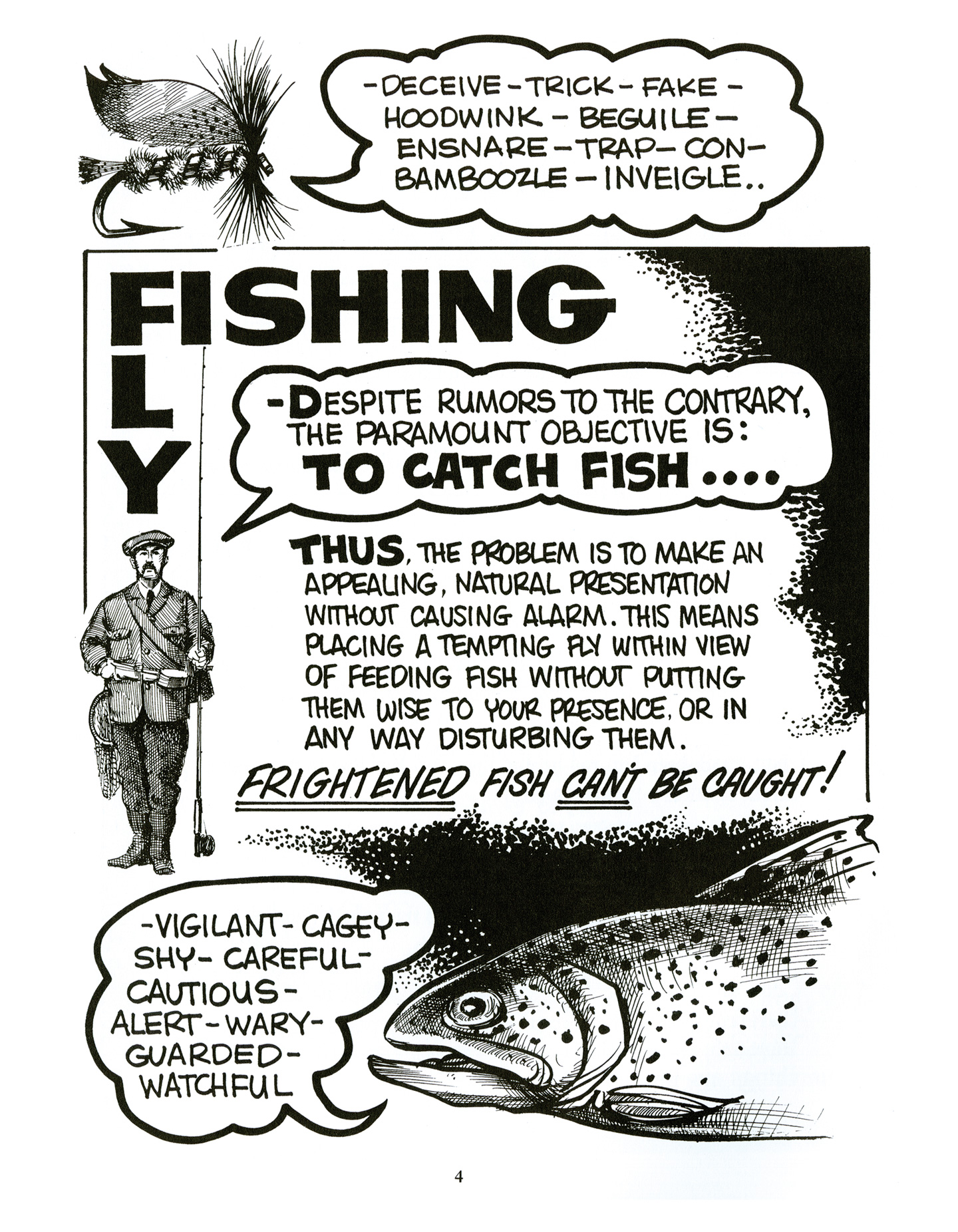

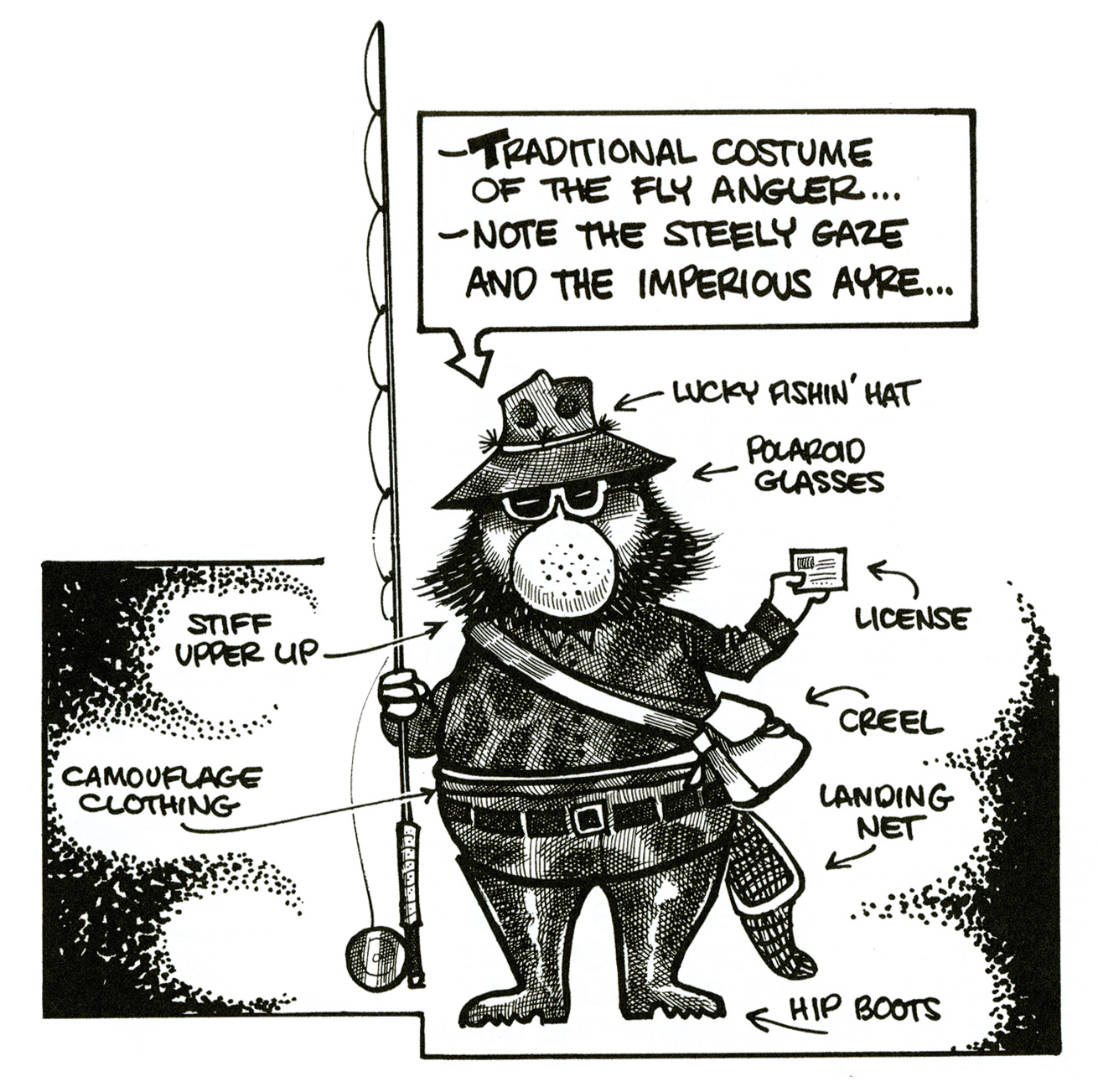

ABOVE Appearing on page four of The Curtis Creek Manifesto, this illustration is a perfect example of Anderson’s immense talent—meticulous draftsmanship, an easy, engaging style, beautiful lettering and approachable, humorous writing.

Illustration: The Curtis Creek Manifesto, Sheridan Anderson, Copyright 1978, Frank Amato Publications, Portland, OR

Sheridan wandered into the climbing scene at Yosemite by way of Reno, NV; Bishop, CA; and Salt Lake City. He was born in 1936 outside of Los Angeles, but grew up in Utah, where his two purposes in life were to fish and draw. “Sheridan could get right to the heart of a person,” his brother Michael Anderson said. “Even as a kid, he could make the magic strokes that would make a person come out in a drawing.”

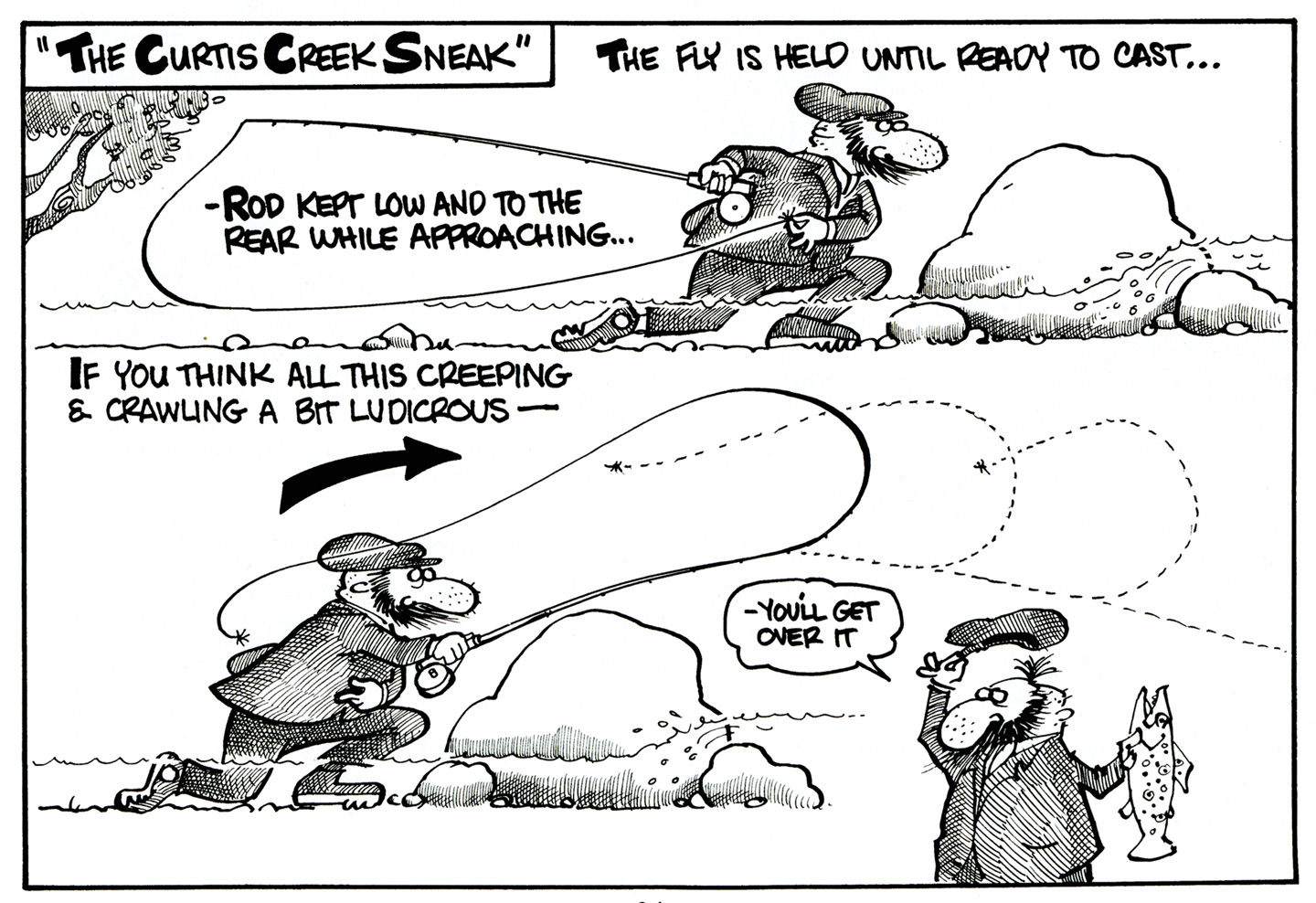

“I went fishing with him once or twice,” he said. “I spent most of the time untying knots. Sheridan was down low the whole time, crawling around and sneaking up on fish—I didn’t get it.”

The Andersons were not a fishing family, but Uncle Grant, who married in, changed that. “Sheridan really looked up to him,” Anderson said. “Grant would spin these corrupt stories that couldn’t have been more than half true, but we didn’t care because he told them so well.”

And he taught Sheridan to fish.

Grant Wooten is the first person listed under The Manifesto’s “Acknowledgements and Thanks,” alongside his photo—the only other photo in the book besides the author’s. “Without [his] genius,” Sheridan wrote, “this book would not have been possible.”

“I got hold of some correspondence later on,” Anderson said, “and he asked Grant to go in on it with him. Grant told him, no, this is your baby. You can do this.”

After high school, Sheridan studied art at the University of Utah, dropped out after a semester or two, and in the early ’60s wandered into Camp Four.

Camp Four is a dusty, walk-in campground in Yosemite National Park. But with Half Dome to the east and El Capitan to the west, it was, and, for all I know, still is the heart of American rock climbing. Sheridan took part in at least two first ascents—Andy’s Inferno in 1964, and Aunt Fanny’s Pantry in 1965—but, by all accounts, he was never an elite climber.

Yvon Chouinard, founder of Patagonia, was an elite climber. The year Sheridan climbed Andy’s Inferno, Chouinard was part of the first ascent of the North America Wall of El Cap without fixed ropes. The next year he climbed the Muir Wall. But as a teenager Chouinard had spent an inordinate amount of time poaching panfish from the water hazards at private Burbank golf courses. Like the only two fishermen in any setting, it was inevitable Chouinard and Sheridan would find each other. “There were a lot of people dirtbagging then,” Chouinard said, “but nobody fished except me and him. We’d fish the Merced and all the little creeks. There’s a series of deep pools below upper and lower Yosemite Falls. It was a pretty easy climb, so we’d fish them from a rappel. We caught some nice 14-inch rainbows that way that must have come over the falls.”

Aside from supplying dirtbag climbers with fresh trout, Sheridan was also Camp Four’s artist in residence. The late Royal Robbins would write, in 1984, that Sheridan was, “one of the chief chroniclers of the foibles, vanities and pretensions of the period.” He was friendly, even close with most of the best climbers of the ’60s and, with a knack for reading character and rendering personalities, he wasn’t shy about lampooning them with pencil and paper. “I never met anyone who could do what Sheridan could do,” photographer Ed Cooper said. “He could put a person’s personality right into a sketch.”

“When he got on a project, he’d really go at it in a big way. He liked to work standing up and he’d tack a sheet to his huge wooden easel and just start drawing. Sometimes, when he was really rolling, it would spill over onto the walls.”—Ed Cooper

ABOVE Sheridan Anderson in the panhandle of Golden Gate Park, San Francisco, in October 1967. He is sharing or selling a copy of The Oracle, an underground newspaper whose contributors included such beat writers as Allen Ginsberg, Gary Snyder and Lawrence Ferlinghetti. He is wearing the paint-splashed pants of his sometime profession—a sign painter. Photo: Ed Cooper

In 1966, Ed Cooper had just quit a job at a brokerage firm in San Francisco. He landed in an apartment on Haight Street; a crash pad for itinerant climbers, drug scenesters and garden-variety misfits. Sheridan was there too.

“People were always coming and going,” Cooper said, “but Sheridan and I stuck around.” By sticking around, Cooper and Sheridan got to know each other and agreed to look for somewhere more permanent to live. At the edge of Haight-Ashbury, they found a one-time restaurant being rented as an apartment.

“They still had deli furniture out front,” Cooper said. “We thought it was perfect.”

Sheridan dubbed it the 6th Avenue Delicatessen & Commune. He staged his easel in the dining area and Cooper set up a darkroom in the kitchen.

“When he got on a project, he’d really go at it in a big way,” Cooper said. “He liked to work standing up and he’d tack a sheet to his huge wooden easel and just start drawing. Sometimes, when he was really rolling, it would spill over onto the walls.”

When the work didn’t come easily, Sheridan would stand and stare at the blank sheet.

“Some nights he’d go on benders,” Cooper said. “He’d get real melancholy and sing the old Lee Marvin song ‘Wand’rin’ Star.’ He loved that song.”

Cooper lived with Sheridan for about a year and a half between 1967 and ’68, but the two spent little time together. “I’d be coming back from the mountains,” Cooper said, “and Sheridan would be leaving for the Russian River, the Sierras, or back to Yosemite.”

Climbing writer Joe Kelsey met Sheridan at Yosemite Lodge in the spring of 1968. Sheridan was in Camp Four and Kelsey, who edited a posthumous collection of Sheridan’s climbing cartoons, had just driven across the country with a friend who knew Sheridan and invited him for breakfast. “Of course, I knew who he was from the cartoons he did for Summit,” Kelsey said. “It was really an honor to meet him. I don’t know what I expected, but I was surprised to find this big, boisterous guy with a laugh that filled up the lodge.”

One year, Kelsey arrived in Yosemite to find Sheridan had taken up oil painting.

“Right in the middle of this dirtbag climbing camp is Sheridan copying Remingtons and Charlie Russells,” Kelsey said. “He’d have his easel up against a pine tree—complete squalor all around—painting with oils.”

In 1971, Sheridan fractured a vertebrae in a fall and stopped climbing altogether. “He was always kind of vague about it,” Kelsey said, “but, from what he told me, he fell off a trail hiking in the Sierras.”

According to Frank Amato, he’d fallen off a billboard he was painting. Fellow climber Dick Dumais thought he’d been caught in a rock fall. One magazine bio claimed he’d been “scrambling unroped on his way to a rather informal climbing school run by Warren Harding.”

After the accident, Sheridan drove to Jackson, WY to stay with Kelsey. “He was in pretty bad shape,” Kelsey said. “While we were off climbing, he’d hang around camp and fish. There was a creek running over slabs near camp that was full of tiny, fingerling-sized trout. He’d catch them and laugh his head off. He said it was great practice—that it kept him sharp.”

Kelsey returned to San Francisco sometime in the mid ’70s to find Sheridan already at work on The Curtis Creek Manifesto. Sheridan was living in a funky, slice-of-pie-shaped apartment on Potrero Hill. “I stayed there a few months while I was working in Berkeley,” Kelsey said. “I’d go off to work for the day and when I’d get back there’d be something new hanging on the wall.”

When he needed inspiration, Sheridan would wander down to the casting ponds at Golden Gate Park or over to the Winston fly shop on Third Street. “He started coming in around the time I showed up,” Glenn Brackett, then-owner of the Winston Rod Co., said. “That would have been 1974 or ’75. At that time, San Francisco was the focal point of fishing.”

“A lot of great things came out of the San Francisco fishing scene,” Brackett said. “The Golden Gate Casting Club, the Tyee Club, all the tackle history. And it’s a great jumping-off place for fishing. You could be fishing for stripers one day and steelhead the next. You had great salmon runs on the Eel, the Smith, the Mad, the Trinity—not to mention the small coastal streams. A couple hours away, you had the Sierras and the Truckee and Hot Creek. It was so rich in varied fisheries.”

Sheridan would lay out pages on the counter and he and Glenn Brackett would go over them. “He was all business,” Brackett said. “He came in to talk about his book. He really wasn’t very sociable, but I was very drawn to him.”

ABOVE The more things change.… One of Anderson’s endearing talents was the ability to gently satirize his subjects, pointing out the absurdities, the pretensions and the humor in his subjects. Illustration: The Curtis Creek Manifesto, Sheridan Anderson, Copyright 1978, Frank Amato Publications, Portland, OR

Sheridan would lay out pages on the counter and he and Brackett would go over them. “He was all business,” Brackett said. “He came in to talk about his book. He really wasn’t very sociable, but I was very drawn to him.”

The last time Brackett saw Sheridan was the day Winston Rod Co. left San Francisco for Twin Bridges, MT. It was early Sunday morning, before traffic, and a semi was parked in the road. “Here came Sheridan, wandering along,” Brackett said “We were loading the rod-building equipment into the trailer and he asked if we needed any help. I took one look at him—he’d clearly had a big night—and I told him, ‘No, Sheridan, you just take it easy.’ He had no idea we were leaving, but that was Sheridan—always showing up at strange times.”

Brackett lost touch with Sheridan when he left San Francisco, but when The Manifesto came out he saw that Sheridan had done the job right. “It’s brilliant,” Brackett said. “It cuts through all the bullshit in the fishing business. There was a period of time that we’d provide a copy with all the rods that went out of the shop.”

Painter Russ Chatham also crossed paths with Sheridan in 1970s San Francisco.

“I loved the guy,” Chatham said. “I was in my late 30s then and up for any kind of hijinks. He was obviously on the same wavelength, running around with the ZAP! Comix guys—R. Crumb, S. Clay Wilson—who were some of the smartest and the most bizarre people I’ve ever known.”

In a storage locker in Montana, Chatham has a huge collection of underground comics. “The kind of stuff Sheridan and the underground guys were doing was deceptively simple,” he said. “It seems goofy, but that’s not really right. It’s quite sophisticated, if you want to know the truth.”

Of the underground comic artists, Sheridan was closest with the legendary S. Clay Wilson. In 2008, Wilson suffered a severe brain injury. He rarely speaks, but through his wife, Lorraine Chamberlain, he was able to relate a list of people from the underground circle who knew Sheridan—a list that included the painter David Geiser.

Geiser met Sheridan in 1969 at a comic convention in San Francisco. “This great big grizzly character comes up to my table and starts chuckling,” Geiser said. “He introduced himself and I pulled out a bottle of something and that was that. We were all living deep in the bowels of the Mission. We’d go down to Dick’s Bar to meet Wilson and the rest of the drinking buddies and storytellers. It was a really rolling scene for a neighborhood bar; a couple of big communes close by in the Castro, [writer/editor] Warren Hinckle was right there and he’d bring in Hunter Thompson. It was a real daisy chain.”

Though Geiser was and is a flyfisherman, he and Sheridan never fished together. But Sheridan was adamant about teaching S. Clay Wilson to flyfish.

“Poor Wilson probably thought he was going out to drink Jack and stare at a bobber,” Geiser said. “When they came back, Wilson had this befuddled look. ‘Sheridan’s worse than a goddamn Parris Island drill instructor,’ he said. I asked Sheridan about it later. He shook his head and said, ‘It’s a good thing Wilson can draw.’”

“I loved the guy. I was in my late 30s then and up for any kind of hijinks. He was obviously on the same wavelength, running around with the ZAP! Comix guys—R. Crumb, S. Clay Wilson—who were some of the smartest and the most bizarre people I’ve ever known.” —Russ Chatham

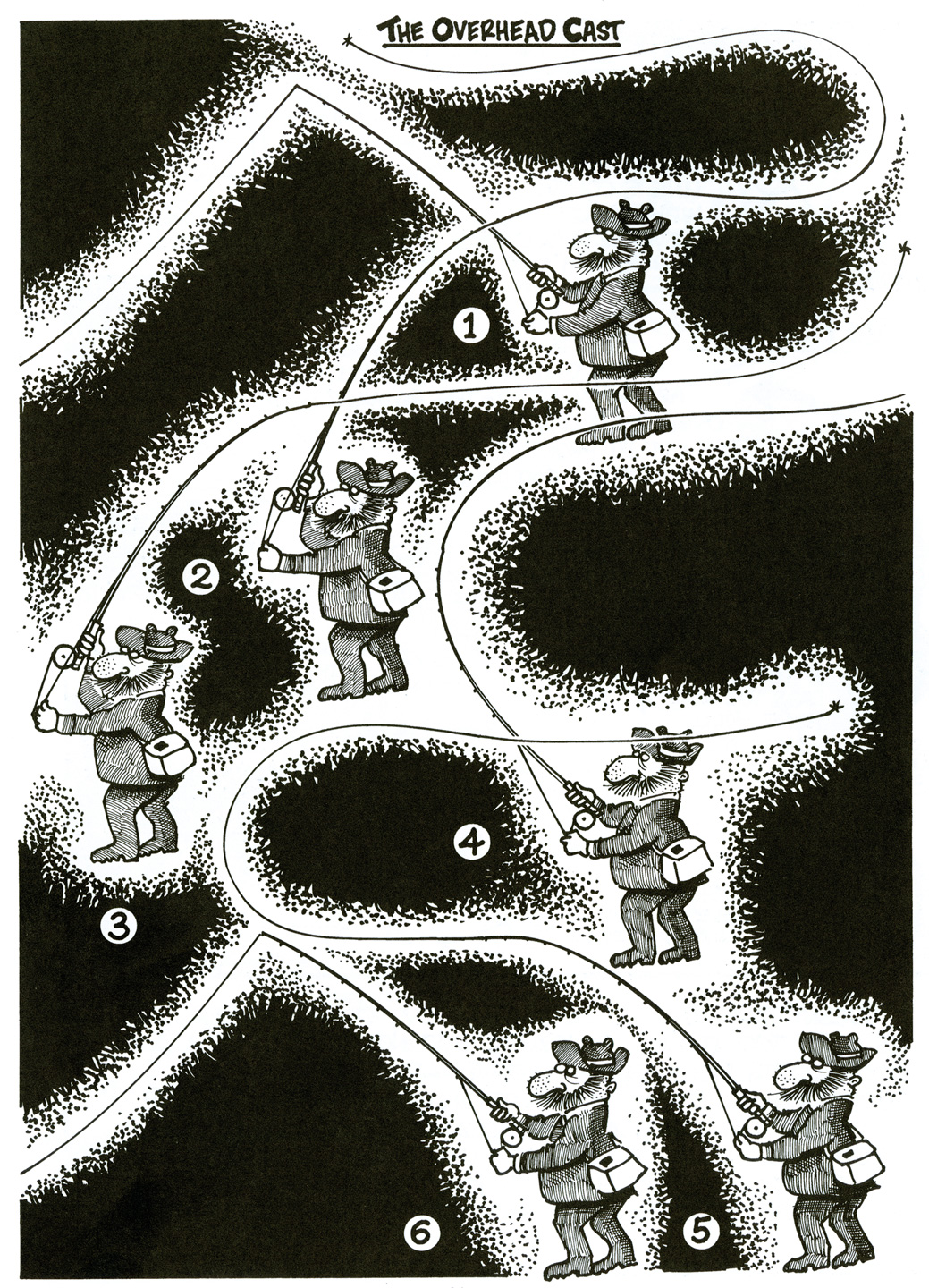

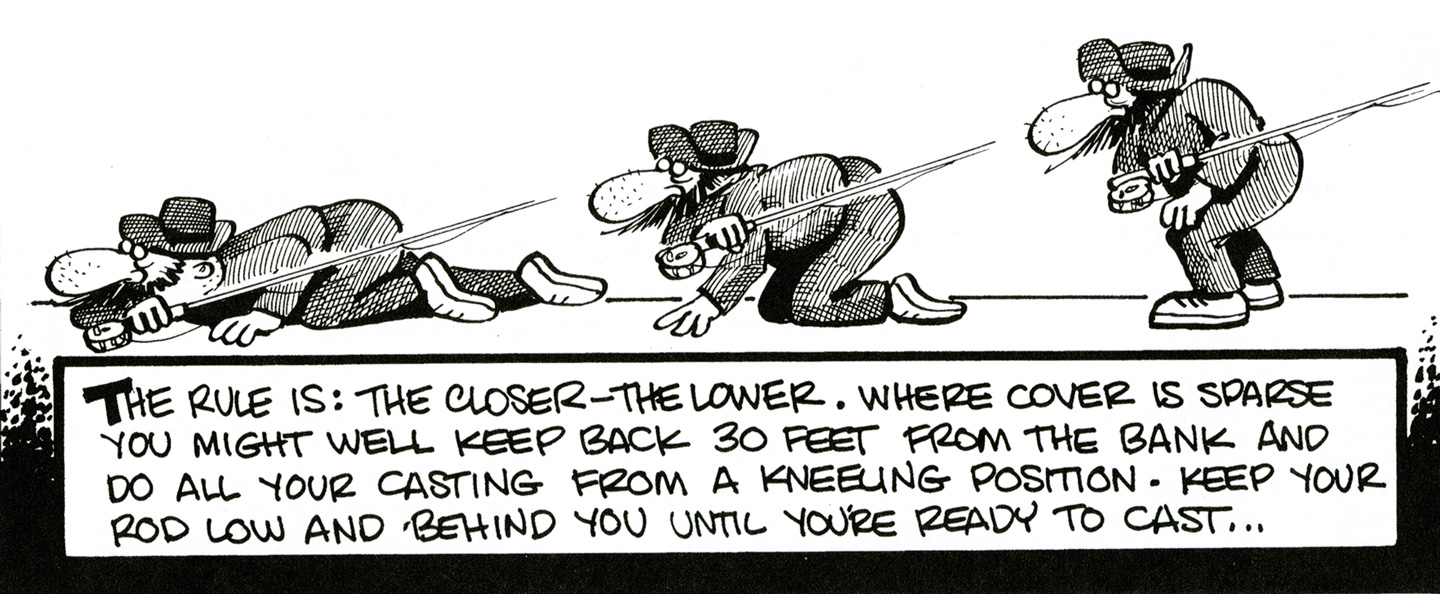

ABOVE Despite Anderson’s humorous, irreverent style, he had the uncanny ability to relate complicated technique in a simple, easy-to-understand manner. Illustration: The Curtis Creek Manifesto, Sheridan Anderson, Copyright 1978, Frank Amato Publications, Portland, OR

In the late ’70s, emphysema forced Sheridan out of San Francisco. He bought a cabin in the high desert of southern Oregon. A short walk from the Williamson and Sprague Rivers, and in need of repairs, he dubbed the cabin the “Visqueen Manor.” Fishing on both rivers for big rainbows and browns can be spectacular—just what a traditional trout fisherman like Sheridan would have been looking for. But Chiloquin, OR, must have been short on the spontaneous, open-ended fun that had been so plentiful in Camp Four and San Francisco.

“He’d hang around the bars in Chiloquin drinking with Paiute Indians,” Geiser said. “One night—after he’d gotten a phone in the cabin—he called to tell me he’d ended up on his back with a revolver in his face. I’m sure he went in there saying, ‘Hey, let’s talk,’ and started in with the John Wayne shtick. I had to tell him to cool it.”

Summers in Chiloquin were a welcome change from San Francisco, but the winters were too much for Sheridan’s emphysema. In the fall, he’d drive east to Las Vegas to stay with his grandmother Hazel. “She was old and feisty and lived a couple blocks off the strip,” Kelsey said. “Her passion in life was the dollar slots. He was there to take care of her, but we were never quite sure who was taking care of who.”

Sheridan would walk his grandmother to the casino every day in the winter and wait at the bar reading Tolstoy and Chekhov while Hazel worked the slots. “He’d call me in the middle of the night howling drunk and lamenting being down there,” Geiser said. “He’d tell me stories about old-timers in Iron Bay work gloves hauling away on the slots with right arms like Schwarzenegger’s. Said he might join Mensa just to find some decent conversation. We were all devastated when his ticker popped.”

At 47 years old, Sheridan died of an acute attack of emphysema on March 31, 1984 in Las Vegas. One of the first calls Hazel made was to S. Clay Wilson, but he was in Scotland. Friend Sabeth Ireland took the message. “I can still hear her saying, ‘Tell Wilson Sherry died,’” Ireland said.

“I had him cremated in Las Vegas and brought him back to California in a little box,” Michael Anderson said. “I kept that box around the house for the rest of the winter.”

In the spring, Michael hired a plane to fly him over the Golden Trout Wilderness. It was a place Sheridan loved, where he had gone to fish and to dry out. The plane took off from an airstrip in Lone Pine; two runways in the afternoon shadow of the southern Sierras. “We were circling up to get enough elevation,” he said. “We kept circling and circling and circling up until, pop, we were over the crest and in the Tunnel Meadows.”

I haven’t been back to the Strawberry Mountains, but now I have my own Curtis Creek—a cutthroat stream in Oregon’s Willamette Valley. I lost touch with the professor and gave his copy of The Manifesto to a friend. These days I keep several on hand so I can give them away, and for 99 cents at the local Goodwill, anyone can own an instruction manual that is the best way into a sport blessedly full of storytellers, oddballs, bullshitters, artists and raconteurs. Sheridan was all of those things and described himself as a “foe of the work ethic.” He was an engaging eccentric and massive talent who left the world too young, but left behind a work that distilled an ever-evolving sport into 48 timeless pages. Even now, 33 years after his ashes have settled over Tunnel Meadows, his old friends hear new stories and say, “Hell, I never heard that one, but it’s true—whether it happened or not.”

Sheridan would walk his grandmother to the casino every day in the winter, and wait at the bar reading Tolstoy and Chekhov while Hazel worked the slots.

ABOVE Anderson was a huge proponent of stealth and concealment in his approach to flyfishing. “The Curtis Creek Sneak,” is an excellent example of his genius mix of technique and humor—not to mention beautiful and meticulous drawing. Illustration: The Curtis Creek Manifesto, Sheridan Anderson, Copyright 1978, Frank Amato Publications, Portland, OR

ABOVE Spend a few moments with The Curtis Creek Manifesto and you are guaranteed to become a better angler, or at least pick up a tip or two. “The Book” has provided more “light-bulb moments” to anglers than perhaps any other modern instruction manual. Illustration: The Curtis Creek Manifesto, Sheridan Anderson, Copyright 1978, Frank Amato Publications, Portland, OR

This story originally appeared in The Flyfish Journal Volume 8 Issue 4.