Essay

Whistling Gophers

And then there were the bamboo fly rods. We all admire them, own more of them than we need, fish with them often, and get tongue-tied when trying to explain to inquisitive bystanders what it is we like about them. Some are honestly curious, but most just can’t get past the high prices that are charged for some of these rods and are what another friend calls “whistling gophers” who ask, “What’s one of those go fer?” and then whistle loudly when they hear the answer.

Vince also builds them. He was always one of those hands-on perfectionists (he trained as a machinist and is a good finish carpenter, among other skills), so he isn’t as intimidated as most would be by the prospect of working to tolerances of a few thousandths of an inch using hand tools. (Those, by the way, are the kind of traits that describe every rod maker I’ve ever known.) By the time I met him he’d already made his first rod at a seminar in Arkansas. As first rods go, it was better than most, but although he fished with it from time to time and didn’t hate it, he wasn’t all that pleased with it either, and wanted to do better. This was the inflection point at which someone like Vince decides to learn the craft, while someone like me long ago decided to just buy rods from people like him. Likewise, when I have a job that requires a tractor, I’ll hire a guy, but Vince buys the tractor and does it himself.

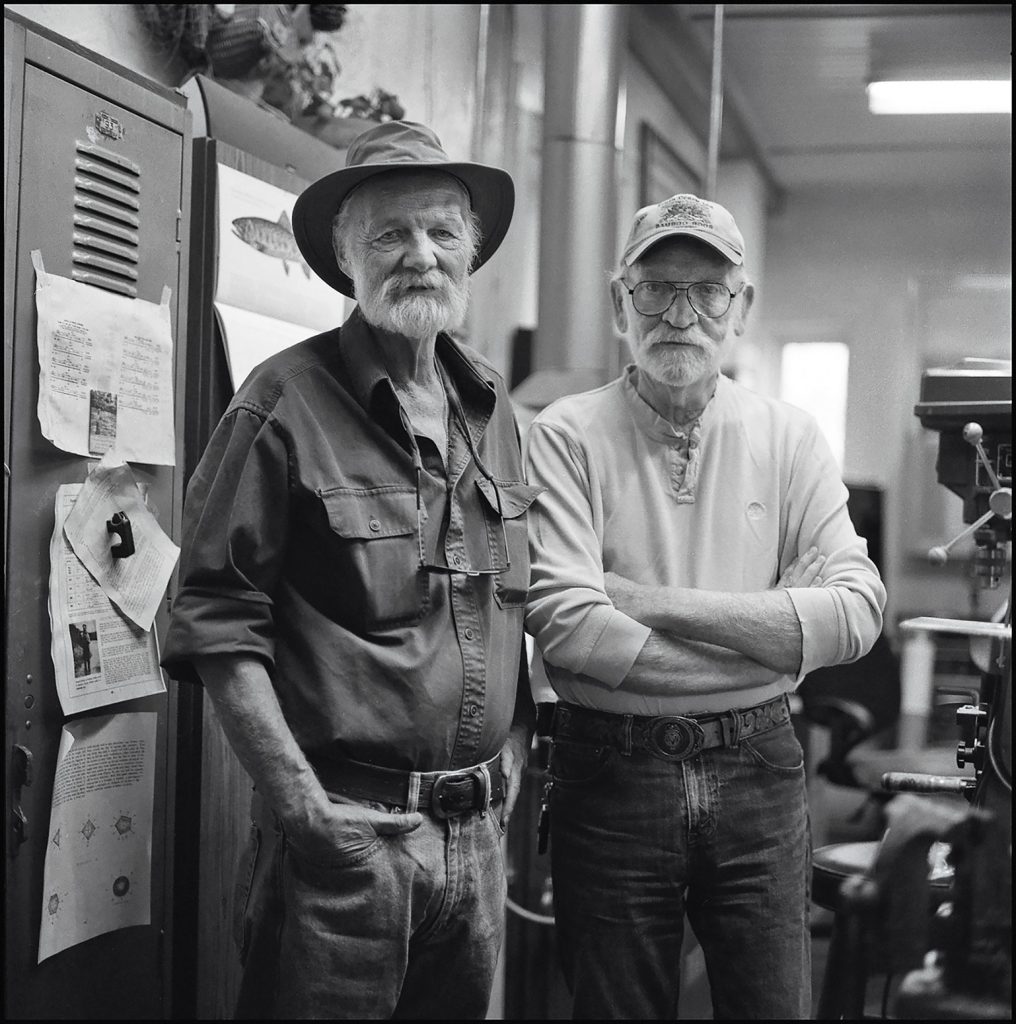

John Gierach and Mike Clark pause in Clark’s bamboo rod workshop, South Creek Ltd., in Lyons, CO. A longtime friend of Gierach, Clark has been making bamboo fly rods for over 40 years. He is considered a master of the art, with a waiting list measured in years and prices that reflect the quality of his work.

I don’t remember if Mike knew beforehand that Vince built rods or if he learned of it during that trip. These things are just in the air, although I will say that among anglers the fact that someone makes bamboo rods would come up pretty early in a conversation. When Mike asked about the rods, Vince handed him one—a 7 ½-foot 5-weight—and told him to go ahead and fish it that day. This was the same soft sell I’d seen other rod builders use. Words fail when it comes to describing the action of a fly rod, so why not just let the test drive do the talking? The conditions on that trip couldn’t have been better for it. It was October, on a good tailwater fishery in the headwaters of the Colorado River with multiple hatches lasting from 10 a.m. till 3 p.m. most days—tailor made for light bamboo rods and the floating lines and small dry flies that show them off best.

I also don’t remember if Mike ordered a rod while we were still on the river or if he waited until he got home. In the same situation, I’ll give it a week or so to try and talk myself out of spending the money for yet another rod, and then when I can’t, I’ll call the guy—who, incidentally, never sounds surprised to hear from me. Most rod makers can tell when you’re hooked but understand they might have to give you some line before they land you. I do remember that Mike wasn’t especially in the market for a new rod, but we all know what that means. Right off the top of my head I can name four rods I bought when I wasn’t in the market and if I pondered it for a while I could probably come up with a few more.

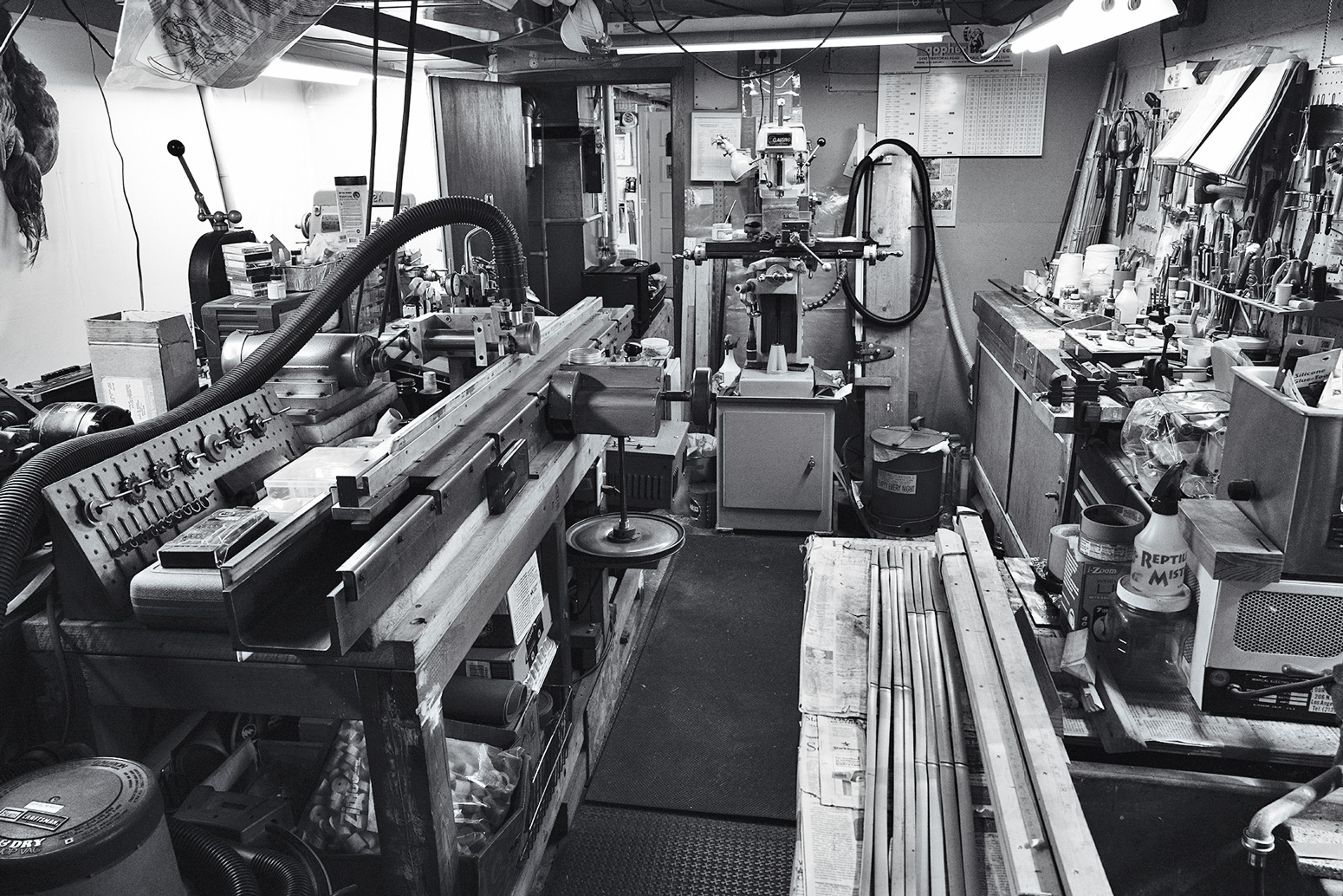

A Rivett 608 metal lathe, produced in 1956, which spent its early life at the Boeing airplane plant in Seattle, before rod maker Mike Spittler bought and restored it. The lathe is capable of unimaginable precision; a screw was once turned with a lathe of this same model at Johns Hopkins to a tolerance of 1/50,000,000 of an inch. You can rest assured Spittler’s ferrules are precise.

At this point, Vince had a couple of standard models, would accept orders and had a business card in lieu of a catalog or website—essentially operating by word of mouth—but he had too many other irons in the fire to build rods full time. So the one stipulation to Mike’s order was that he have the rod by spring. It’s a consideration. A rod maker once told me that something like 400 separate operations go into the making of a bamboo fly rod. Many of them are time-consuming in their own right and some also require downtime for drying and curing, so delivery dates can stretch out, especially when the builder has a dozen other projects in the works, plus fishing. And no one in his right mind would buy a rod from someone who doesn’t go fishing.

I’ve known a handful of rod makers—some well, others in passing—and no two of them went at it the same way. Some learned the craft from more experienced builders and others were largely self-taught. Some kept pretty much to themselves while others went to every conclave they could find and flitted around the online community of rod builders and collectors like hummingbirds. Some were self-proclaimed hobbyists who were eventually talked into making rods for a few friends, and that’s as far as it ever went. Others tinkered with rods on the side for years and then got serious when they retired, recognizing rod making as a better way to supplement Social Security than being a greeter at Walmart. Others took up rod building by way of a conscious career change, with varying degrees of success. A dedicated handful go to their shops every morning and bang out rods at the rate of as many as 40 per year. Most others keep more forgiving schedules.

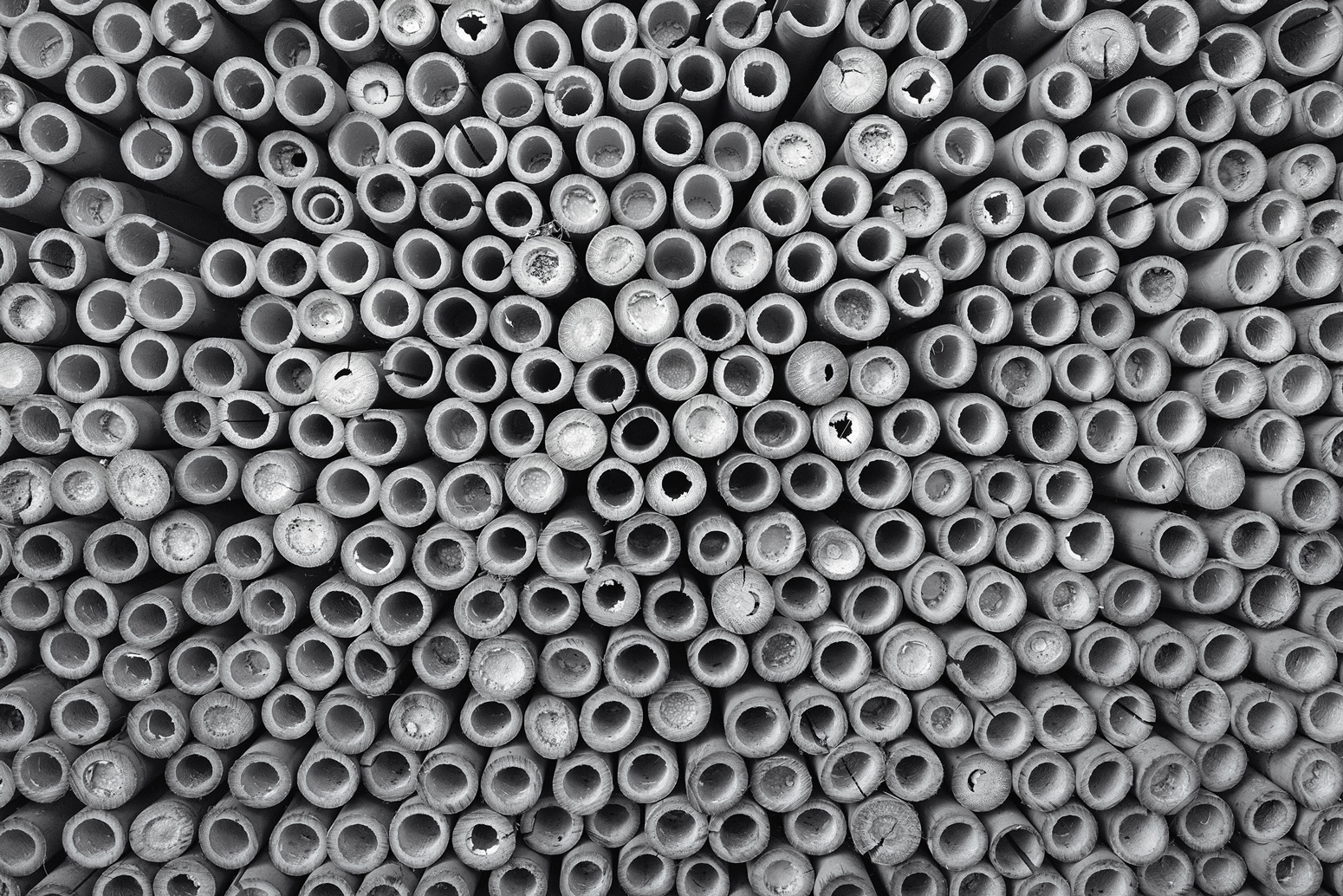

Tonkin bamboo grows in southern China along the Sui River and has been used to create bamboo rods for over 100 years. This rack of bamboo was cut, dried and shipped to the United States over 40 years ago. Each culm is roughly 12 feet long.

The rod Vince made for Mike is based on one the late John Bradford made for me in 2002. He called it the “Stage IV.” John told me at the time that it was made on the famous Payne 197 taper he’d “tweaked a little,” although he had the good sense not to say he’d “improved” it. He didn’t specify how he’d tweaked it, assuming correctly I wouldn’t understand what he was talking about. Sometime later, Vince was busy learning about rod tapers by casting the best rods he could get his hands on and putting a serious study on the ones he liked best. He’d cast them, measure the dimensions of their tapers, cast them again, stand at a distance to watch others cast them, all the time fixing in his mind how the tapers related to the rod’s action. Do this enough and you become like a musician who can look at a written score and hear the music in their head. He did that with several of my rods, but he held onto that Bradford for so long I began to wonder if I’d ever get it back.

At least on paper, determining a rod’s taper is a logical procedure. You take the measurements off the existing rod with a micrometer and make an educated guess as to how much to subtract to allow for the varnish (two thousandths of an inch is the usual standard) to arrive at the actual dimensions of the unfinished shaft. Then you do the calculations that translate a hexagonal rod into the six triangular-shaped splines that, when glued together, will make the taper. Those are the measurements to which you set your planing form.

Silk thread has long been used to wrap the guides and ferrules of bamboo rods. The thread is fine and strong and, once varnished, reveals a translucent, jewel-like appearance.

Stanley hand planes, seen here in the hands of maker Dave Norling, are used in conjunction with planing forms to shave the individual strips of bamboo that are eventually glued together to form the traditional bamboo rod.

But in reality, reproducing a rod isn’t as straightforward as it sounds. I don’t own a 7 ½-foot Payne made by Jim Payne himself—they’ve always been beyond my budget—but I’ve cast a few of them, as well as any number of others that were built to the same iconic taper. If this were a simple matter of reverse engineering, all those rods would have cast the same—but they didn’t because there are too many variables. Whether the bamboo was heat treated—and if so how and how much—makes a difference, so does the glue used to fasten the splines together, so does the node spacing; and so does the culm of bamboo that was used, which a maker selects knowing that a big culm has larger, stiffer fibers than a smaller one. So on and so forth. All that assumes the absolute accuracy of your micrometer and the settings on your planing form, neither of which are foregone conclusions.

And there are imponderables, like the belief among some that a bamboo rod mellows with age and use the same way an already good violin will sound even better after being played for a hundred years than it did when it was new. Offhand, I can’t think of a way to verify that, but I’ve always thought it sounded right.

There are well over 100 steps involved in making a single bamboo fly rod, a process that can take months. I have a few of them now, from makers I know and admire, including Vince Zounek who made this one for me last winter. As I write this, our trout season is two days away from ending, and I’m already looking forward to fishing it next season.

For that matter, rod builders are hopeless tinkerers who are unable or unwilling to leave well enough alone, so they don’t. Over the years I’ve met two guys who claimed to be faithfully reproducing the tapers of classic rod builders—Everett Garrison in one case, Goodwin Granger in the other—but everyone else tweaks and fiddles compulsively, fine-tuning the already fine-tuned, even if a sympathetic-but-objective observer like me can’t tell the difference. They remind me of some editors I’ve known who’ll redraft a perfectly good sentence for no other reason than that redrafting sentences is in their job description. And this is further complicated by the counterintuitive fact that a few thousandths of an inch more or less in one place on a blank won’t make much difference, while in another place it can either improve or ruin the action.

That’s why an alchemy is attached to the work of particular rod makers that’s hard to put a finger on and impossible to completely reproduce. So a Payne becomes a Bradford, which becomes a Zounek, and although they all seem familiar, they’re not identical. (For that matter, the Payne taper that served as the benchmark didn’t come out of nowhere either. Payne was a second-generation rod builder whose father’s roots reached back as far as Hiram Leonard, the 19th century rod maker who Ernest Schweibert called the “father of the modern fly rod.”)

A 4 or 5-weight, 7-foot or 7-foot, 6-inch bamboo fly rod is the perfect complement to a spring creek in the Driftless region of the Midwest, with the moss-covered limestone and deep cold runs that hold both brown and brook trout.

It’s that sense of familiarity that always attracts me to rods. Among the light bamboo fly rods of mine that Vince looked at are 7 ½-footers by Bradford, Leonard, F.E. Thomas and Granger; 7-foot, 9-inch rods by Mike Clark and Walter Babb, and a pair of 8-foot 4-weights by Thomas and Charlie Jenkins. They’re not all the same, but they do all share the quick, tippy dry-fly action that’s characteristic of Golden Age bamboo rods (which lasted roughly from the late 1920s to the early 1950s), so that after your first two or three casts with any one of them, you get the friendly feeling you’ve been fishing it for 20 years. (Rods that are described as “demanding” are fine for connoisseurs, but I’d rather they make their demands of someone else.) It’s possible none of them are perfect fly rods in any objective sense, but any of them could be in the right hands. Charlie Daniels once said there’s no difference between a fiddle and a violin, it’s all in how it’s played.

The technical voodoo behind the best bamboo rods remains a mystery to me, as it should. All I know is that at its best, craftsmanship goes beyond mere do-it-yourself projects and begins to flirt with artistry. And there’s also an element of sentiment to it. I know or have known some of the makers whose rods I own, and that makes a difference. It’s hard to explain, but as someone who once kept laying hens, I can testify that eggs taste better when you know the chickens that made them. And no, I didn’t give them names; I referred to them collectively as “the girls” to distinguish them from my cantankerous rooster.

Some things live on long after their creators have shuffled off; this is certainly true of bamboo rods, but it can also be true of the tools used to create them. The base of this planing mill was built by legendary Michigan maker Morris Kushner; after Kushner’s death in the early ‘70s it ended up with Bob Summers, another Michigan legend. It now resides in the shop of Minnesotan Mike Spittler, a respected and well-known maker of Quadrate, or square-section, rods.

When I first got interested in bamboo rods, I was just another whistling gopher floored by what some of them cost, so I made do with good old rods by makers who hadn’t become collectible yet. But as time went by, it became obvious that some of those makers were underrated at the time and most of them did eventually become collectible, so as it turned out I’ve gotten more than my money’s worth. As I learned more about what it took to make them—not just the one rod, but the long, uphill slog of learning and perfecting the craft—the prices started to look more reasonable, and then I began to wonder why they don’t cost more than they do. As the old saying goes, “You couldn’t pay me enough…”

Before Mike’s rod was shipped off, I cast it in the pasture in front of Vince’s house. (I didn’t think Mike would mind and he didn’t.) It was what I expected: friendly, familiar, forgiving, effortless—pick a word—with the right balance and heft and just the right combination of give and resistance to make a fly line feel weightless. My friend Ed Engle once said the difference between graphite and bamboo fly rods is that graphite shoots line, while bamboo casts it. As a description of something indescribable, I thought that came pretty damned close.

A fine brown trout on a spring day, caught with the rod built by my friend Vince Zounek.

I haven’t cast all the rods Vince has made, but I’ve cast a lot of them and have fished with a couple, knowing that you’ll learn more about a rod in a few hours on a trout stream than you will in a few minutes on the lawn. Vince likes to try them out on me, not because I’m such a great fly caster, but because he thinks if I didn’t like a rod, I wouldn’t pull my punches. In fact, if it ever happened, I probably would pull my punches, but he’d be able to tell.

The day after Mike got the rod, he took it to one of the spring creeks near where he lives and caught, among other fish, a nice fat brown trout and sent a photo of it to Vince. Two photos, actually. One was of the trout and the rod and the other was a close-up of the signature wraps on the rod—a warm brown with a reddish-orange tag—next to the trout’s adipose fin to show that the colors matched almost exactly. Rod makers sometimes add subtle touches like that on purpose, even though most of their customers will never notice. John Bradford once spent weeks formulating a wood stain that would make his maple reel seat spacers exactly match the color of the bamboo on his rods. It’s not the kind of thing that jumps out at you, but it does have the subliminal effect of making the rod seem somehow more finished than most.

When I asked Vince if he’d purposely chosen the wrap colors on his rod to match the adipose fin on a brown trout, he said no, although he did think it was a nice coincidence.

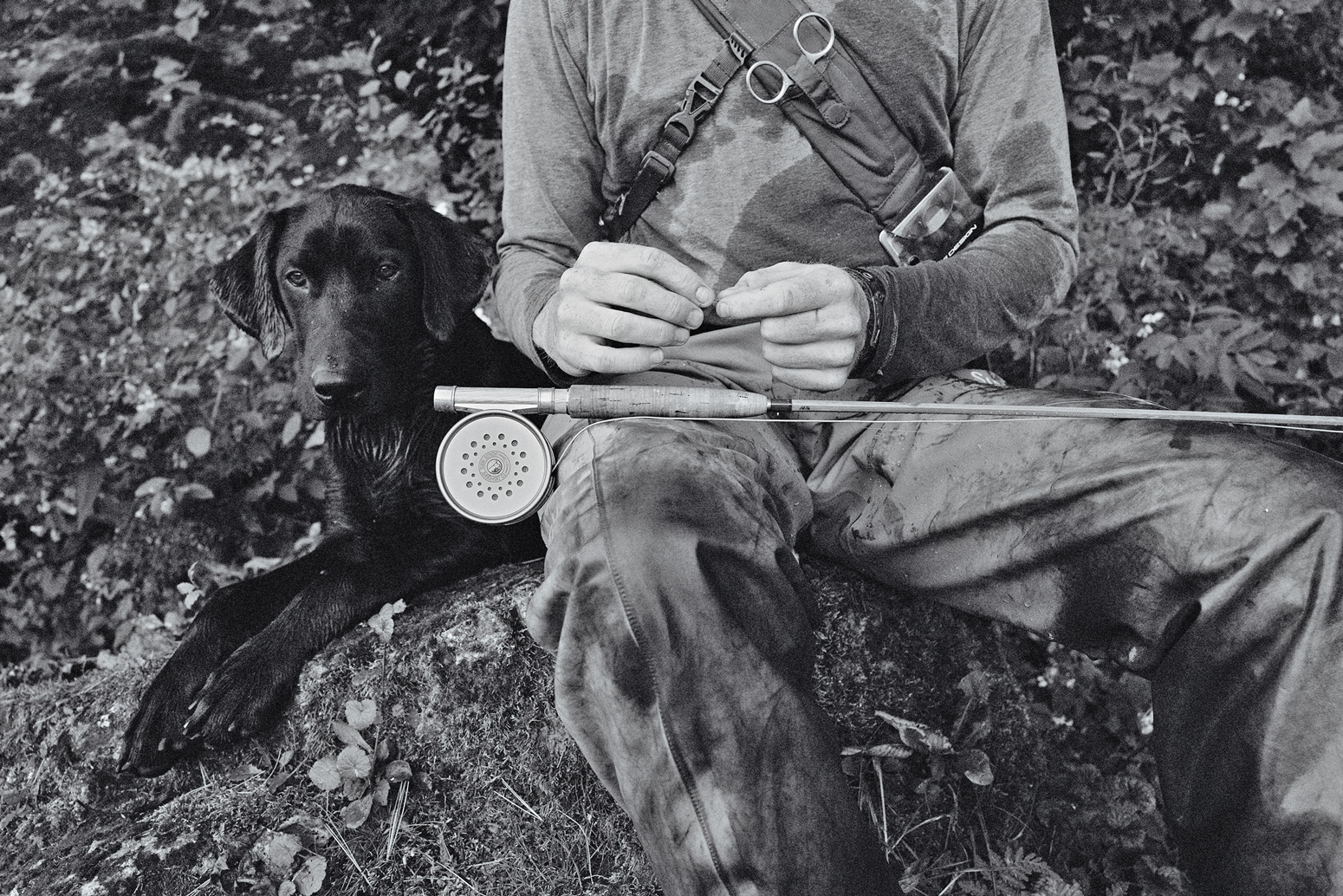

Dan Frasier and his 6-month-old black lab, Leo, take a break to tie on a new fly before continuing up a spring creek in southeast Minnesota. The H.L. Leonard rod resting on his knees is several decades older than Dan.